|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

By Larry Nau

March 16, 2020

Planting several conifer seedlings at a time? Consider adding the dibble bar to your garden arsenal.

Our journeys with our beloved conifers take us down many paths, many of which are totally unexpected. So it was on a hot, late October’s day in Virginia. I would be part of a team of 7 people with conifers and a dibble bar.

We know and cherish conifers, but a dibble bar was a totally new experience for this conifer grower. Simply, a dibble bar is a tool used to plant trees on a large scale, primarily for reforestation projects.

Dibbles consist of a steel blade formed with a 3 to 4 foot handle. It is used by thrusting it into the ground, pushing it back and forth to create a tapered hole, in which to drop a young seedling. Working with a dibble bar is a great aerobic workout and certainly rivals any gym time!

conifer trees on a large scale

Joseph Pines Preserve and Conifer Reforestation

Our team almost completed the longleaf pine planting

of the initial 32 acres at Joseph Pines Preserve (JPP) during October 2015. Thanks in part to the help of the American Conifer Society, JJP has another 25,000 native Virginia longleaf pine to plant—making the JJP nursery the largest in Virginia for

native LLP production.

Work will begin in early 2016 to clearcut an additional 50 acres on the preserve. This land will be restored to a native longleaf pine forest with the planting of the two-year-old seedlings. Planting 25,000 seedlings

by hand is a daunting task. However, Phil Sheridan feels it is important to vest JJP and Meadowview staff, naturalists and citizens in this effort to restore the longleaf pine.

Labors Beyond the Dibble Bar

Participating in the longleaf pine planting is not just the use of

a dibble bar. Seedlings need to be transported to the site and watered. The LLP seedlings are grown in IP 45 trays; many of which were bought with an ACS grant. Presently the seedlings are manually extracted by hand, with the use of a wooden dowel

and mallet, labor intensive for sure.

With all this energy expended, food preparation for the volunteers becomes another challenge and necessity. This is a group effort, where the help and talents of many people are required.

Biological Research Station

It was encouraging to learn that the American Conifer Society’s Southeast Region reached out to Phil Sheridan. Phil and JJP are one part of an extensive effort in the Southern United States to restore Pinus palustris to its traditional range. I hope the ACS continues to find ways to expand its support of JJP and other conifer related conservation projects.

For myself, I like the dibble bar and the outcome of planting longleaf pines for future generations to enjoy. Odds are I will return to Virginia this October, to experience Dibble Bar 201 and help to plant those 25,000 seedlings which the ACS helped to create.

Photographs by Larry Nau.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

By Larry Nau

November 29, 2019

Learn about the replanting efforts for one of nature's valuable conifers.

The Longleaf Pine and a Conifer Ecosystem

In Virginia alone, it’s estimated that by 1850 more

than one million acres of longleaf pine forest had disappeared. Today there are fewer than 2,000 mature Pinus palustris remaining in the natural forests of Virginia. Pinus palustris has been eliminated from its northern most range

in the USA. Longleaf pine forests are an important component of the ecology of the American Southeast.

It is a keystone species and mediates fire effects which provide habitat for a wide variety of plant and animal species including bobwhite

quail, red-cockaded woodpeckers, and Bachman’s sparrows. Since the forests often contain seepage bogs and flatwoods, Mabee’s salamanders, pitcher plants, and sundews can be found.

Species of orchids, lilies, wildflowers, and sedges also

proliferate. Longleaf pine can live for more than 300 years. As a result, they may be most helpful for long-term carbon sequestration. The utilization of carbon is not only good for the Southeast, but our entire planet.

Restoring Conifers and Biodiversity

There are many efforts directed toward the restoration of

the Pinus palustris. The federal government, numerous environmental groups and even private landowners have partnered to replant the longleaf pine. One such effort is located in Virginia’s Sussex County at the 232 acre Joseph Pines Preserve

(JPP). Inside the Joseph Pines Preserve, over 60 acres of land have been cleared and burned to plant over 10,000 native, Virginia longleaf pine trees.

Seed was collected from the last long-leaf pine trees in Virginia. These seedlings were

raised in Woodford, Virginia. In addition, the goal of the Joseph Pines is to restore the bio-diversity of the yellow pitcher plant, Sarracenia flava, to the traditional longleaf pine–pitcher plant ecosystem.

The preserve is also

dedicated to capturing the entire Virginia longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) genome by grafting, fascicle rooting, or seed propagation. Joseph Pines Preserve has recently purchased an adjoining property to create The Center for Biodiversity.

This facility will serve as an education and training center and will support conservation and restoration efforts.

At the 2014 Board of Director’s Meeting in Atlanta, the ACS Board approved a donation of $1,000 to the Joseph Pines Preserve

from the ACS Endowment Fund. These funds will assist JPP’s efforts to propagate, replant and preserve the native Virginia longleaf pine. This donation marks the first time the ACS has actively supported an effort to conserve conifers in the wild.

Thank you to the Board as the ACS fulfills another important aspect of its mission.

Photographs by Larry Nau.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

By Web Editor

February 15, 2020

Find out what works and what does not in the battle against fungi.

Colorado blue spruce)

Much of our country has been inundated by flooding this spring. Nothing has been able to hold back the waters. Levees, dams, and sandbags have failed to stem the deluge. “Water wins!” Mary Beth Cunningham, a friend, neighbor, and lake-dweller, said while watching lake waters swell over docks and property.

All residents can do is sit by powerlessly while their lives sink under water. What is going on? What can we do about this, especially when fungus and mold follow on the heels of the floodwaters?

While on tour at Conifer Kingdom, Boring, OR, during our recent 2019 National Meeting, Tom Cox asked me what I wanted to know about conifers. As we walked among the rows of plants, I told him about what has been going on with needle cast on some of the conifers at my home in Adrian, MI; where, to date, it has rained more than 2/3 of the days of each month since April. His answer was simple, profound, and immediate: “It’s a drainage issue.”

Strategy Development in Conifer Fungal Warfare

A drainage issue? On the plane ride back to Detroit from Portland, OR, I passed some of the time going over what Tom had said. I live in USDA Zone 6b. Decades ago, my zone was listed as 5. The springs have become wetter.

The summers are now characterized by prolonged droughts. The winters are dotted with repeated polar vortexes. Are these elements of climate change, or is nature just running its course? Whatever the causal agent(s), what do I do to combat the negative effects of too much water on my conifers, if I can?

We humans are resourceful. Anthropologists and archaeologists have traced the progression and survival of humankind from isolated clusters of people, to migrations, to the development of tools, to the founding of cities and nation-states. Brainpower and knowledge are what have propelled us to where we are, and brainpower is what will save us, and our conifers.

With the help of others, I have developed a new planting strategy that should help all conifer lovers facing climatic changes. I came by this through trial and error and good luck.

Connecting the Black Dots: Fungal Diseases in Conifers

Several years ago I saw black dots on the

needles of several of the conifers that I had planted in low-lying areas of my property. Experts told me that fungus was the culprit. One nurseryman even performed an unsolicited inspection of my garden. He offered to “take care of the fungus” for

$4,700 dollars per year. He also told me that there would be no guarantee that the conifers would survive the anti-fungus treatment.

My go-to horticulturist, Steve Courtney (ACS National Office Manager), responded to my query about the

value of the fungus-eradication program with, “It is a waste of money!” I abandoned the expensive remedy and bought two chainsaws instead, one regular one and one on a pole. However, the question lingered as to how this fungus problem started. What

was the beginning?

The Relationship between Fungi, Conifers, and Humans

I threw myself into fungus-research. Fungi have been part of the life of the Earth for over a billion and

a half years. There are close to 3.5-million species of fungus on the planet. That is a daunting number. Fungi attack plants and humans alike. For example, Claviceps purpurea (rye ergot fungus), causes ergot poisoning, which, in turn, has

been linked to the historical cause of aberrant and hallucination-induced behavior in humans, specifically in those individuals labeled witches and werewolves.

Temporal and secular records of trials from such post-flood areas along the

riverbeds of Medieval Europe and into the 16th Century provided researchers the bases for their findings. The Berserker of Scandinavia were subject to the hallucinating effects of fungus, too. Those warriors consumed the mushroom Amantia muscaria (fly agaric), known for its mind-altering effects, in order to rev up their battle-frenzy, der Berserkergang. They fought like men possessed. Fungus on conifers causes the trees to go berserk, so-to-speak, performing a Totentanz, a dance of death.

The needles of conifers turn purple, brown, and then abscission drops the needles to the ground where they re-infect the trees.

Needle Cast Fungal Disease in Conifers

Two specific fungi, Rhizosphaera kalkhoffii (Rhizosphaera

needle cast) and Stigmina lautii (Stigmina needle cast) are needle cast agents. The fungi grow after excessive water, warmth, and lack of sufficient drying time. However, there may be remedies.

Jack Wikle, ACS member and bonsai

curator at Hidden Lake Gardens (Tipton, MI), advised me in 2009 to plant conifers high. He even suggested that I bury drainage tile around the rootballs of conifers to keep the trees from sitting in a clay-bowl of water. I followed his advice.

Then I met Jared Weaver, ACS member, former Board member, and City Arborist/ Forester for Bowling Green, KY. Jared has written about the natural dropping of the seeds of trees onto the surface of the ground by birds and wind. Roots begin growing

on the surface and, then, reach down into soil. His knowledge challenges the notion that rootballs of trees should be buried below grade or even at grade. Conifers stand a better chance of survival if they are planted high, not in volcanoes, but on

the top of slight mounds, above grade, 1-2 inches.

A 3-Pronged Strategy to Fungi Control in Conifers

Then came the analysis Tom Cox provided me. Combine that with the advice of

Jack Wikle and Jared Weaver, and we ACS members have and can share this three-pronged response to fungus-causing conifer demise with the general public.

We wrap conifers with burlap to ward off winter scald, erect screens around conifers,

plant the trees away from damaging environmental effects, correctly water the conifers in after planting, pay close attention to USDA zones. Now, we can recommend the need to provide proper drainage. If we cannot lick the water and fungus of the environment,

we can respond.

Plant certain species of conifers on a slope. Thank you, Tom.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

How to Design Your Personal Conifer Garden: Color, Texture, & Size

By Web Editor

April 19, 2020

Get started on designing and landscaping a conifer garden with your personal style.

The conifers, Red Star™ Atlantic white cypress (Chamaecyparis thyoides ‘Rubicon’) (left) and Confucius Hinoki cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Confucius’) (right)

“How do I begin?” In my garden designing career, I have often heard this question from new gardeners who want to start a conifer garden with a few tiny conifers.

“What could you do with these tiny conifers, plant them into a balcony container or right into the ground?” Well, I have some ideas to assist you in creating a personal conifer garden.

Designing and Landscaping Questions to Ask Yourself

As a designer with artistic training, I’m going to suggest that you view each specimen, asking these plant-relationship questions:

- Are all the conifers dark green?

- Are they the same genus (cedar, spruce, or pine)?

- What’s their needle shape or texture?

Answering these questions will enable you to create your own unique, personal garden.

First of all, read about your trees prior to planting. Consult the ACS’ Conifer Database on the website. When you do, you will ensure that you site your conifers knowing their soil, water, 10-year size, and sun requirements. Your specimens will reward you for your research.

Experimenting with Conifer Colors in the Garden

Then, arrange and rearrange your conifers. Experiment with blue next to chartreuse, dark-green next to applegreen, white-tipped next to solid-colored.

Keep shifting the plants into a variety of combinations. You will begin to notice how each plant’s individual characteristics of color and texture play off the others.

The conifers, Dinger Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica ‘Dinger’) (left) and Wintergold white fir (Abies concolor ‘Wintergold’) (right)

Playing with Texture of Conifers and Evergreens in the Garden

Your conifers are the “bones” of your garden. Place each one as if it were the sole plant within your line of sight. When you place larger conifers, situate them in primary positions: on top of a mound, off center within a large, flat area, or near a substantial rock formation.

These then become your focal points. The second tier of planting will be mid-sized conifers, offset from one another to enhance the taller focal points. Think of the soft undulations of branch structure, needle texture, and transitioning heights to connect the two levels.

The Role of Space and Positioning in Designing Conifer Gardens

When I design, I often work with tracing paper over an outlined garden sketch, drawn roughly to scale. Doing so allows one to play with a variety of options on paper first, before committing to planting. You can place potential designs over your scale model until you achieve a pleasing visual arrangement.

Continue trying new ideas until you find just the right combination and design for you. Lay out your plants in a swirl or in concentric circles or in contiguous circles, keeping a focal-point conifer at the center of each formation.

As the conifers fill your garden space, a structural framework will emerge. For example, you may want to grow only conifers, or you may wish to add herbaceous perennials such as Echinacea, Lithodora, or hellebores to provide extra color. The silhouette of evergreens will remain your visual focus in winter when seasonal color has died down, and the perennials have gone dormant.

The conifers, Bruns weeping Serbian spruce (Picea omorika ‘Pendula Bruns’ ) (top) and Gold Strike creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis ‘Gold Strike’) (bottom)

Contrast, Higlights, and Foliage Characteristics in Conifer Gardening

Consider Hakone grass, a mix of ferns, or species tulips that flourish in drier environments to compliment your conifers. Some combinations that I like to include are:

- coral Agastache next to blue Pinus taeda 'Montgomery' (Montgomery loblolly pine);

- Pinus thunbergii (Japanese black pine) underplanted with Tulipa saxatilis (candia tulip).

Consider foliage thickness or opaqueness as well as height in your arrangement. These elements add “weight” to your configuration of plants. Dark colors and foliage dense plants “weigh” more.

Working with the Bigger Picture of Your Conifer Garden

The island planting bed is an ideal place for your most significant conifers. You can view it “in the round” and from multiple angles. Dividing available space exactly in half results in a contrived arrangement.

Remember, your foundation conifer is the reference point, from which you place the remaining plants. Walk around your planting area as one does as the first step in a pruning job. Your goal is to work the entire composition.

Refrain from beginning your garden scene in one corner; rather, sketch and work the entire space. Direct your focus to the bigger picture, growing your specimen collection organically, so that it looks as it would in nature without human intervention.

If you have multiple Mugo pines, consider their structural characteristics and create a windswept arrangement, or place a taller weeping tree to cascade downward toward a spreading dwarf groundcover.

The conifers, Mops mugo pine (Pinus mugo ‘Mops’) (bottom) and Bruns weeping Serbian spruce (Picea omorika ‘Pendula Bruns’) (top)

Grouping Conifer and Evergreen Trees for Effect

Use groupings for volume. In this way, your eye will travel naturally from one plant to another:

Including a variety of color, texture, and form will enhance viewer interest.

Finishing your work involves planting smaller species or flat specimens at the front edges or along pathways, or as connections between diverse plantings. You needn't place every tall plant to the rear, or place the lowest/ flattest conifer in the forefront.

Intersperse low with high, and wide with conical. Most importantly, refrain from lining conifers in a straight row. That creates too much rigidity.

The conifers, Tom Thumb Gold Caucasian spruce (Picea orientalis ‘Tom Thumb Gold’) (left) and blue columnar Lawson cypress (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana ‘Columnaris Glauca’) (right)

Maintaining Your Conifer Garden

If you have limited space for planting, such as a balcony, close-range planting is an option for designing with tiny dwarf conifers with growth rates of 1/4 inch per year.

Sharon Elkan’s container plantings with conifers that were featured in the Fall 2019 CQ are prime examples. A small collection of tiny conifers can be grouped to represent a forest.

Aesthetic pruning will maintain your smaller conifers in a mid-sized, urban landscape and also keep all specimens proportional as they mature. See the Spring 2017 CQ for a discussion of aesthetic pruning by Maryann Lewis.

In ensuing years, your garden will begin to suggest other selections of conifers. A deeper understanding of color, texture, and form will guide you as you choose new plants. Don’t put limits on yourself.

Above all, enjoy the creative process you develop in fashioning a garden that reflects your own taste and your own artistic vision.

Text by Mary Warren. Photographs by Mary Warren, with thanks to the West Seattle Nursery and Garden Center and Bill Hibler, Conifer Buyer and ACS Member.

Mary Warren earned her BFA from California College of Arts and Crafts and a Master of Fine Arts Degree in Sculpture from the University of Washington. She has been gardening since the age of four, when her mother showed her how to plant fragrant sweet peas.

Mary Warren, Gardening Artists, 11/15/19, (206) 348-9332 c, 1816 N. 49th St. Seattle, WA 98103 Email:

This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Conifer Quarterly.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

By Ronald Elardo

November 13, 2019

Follow the experimentation saga of a conifer-enthusiast during winter.

The conifer, 'Irish Eyes' Leyland cypress (Cupressus x leylandii ‘Irish Eyes’)

Of late, I have been experimenting with conifers not rated as hardy for my USDA Zone 5. Some say I live now in Zone 6, but I am not certain of this.

All I know is that conifers that are “soft” to my zone have been appearing at my usual conifer haunts. They include: Cupressus x leylandii ‘Irish Eyes’, Pinus thunbergii ‘Thunderhead’, Cedrus deodara ‘Electra Blue’, Cedrus libani var. stenacoma, and Cupressus glabra ‘Blue Ice’. I could not hold back on buying them. Their texture, color and shape are way too enticing to pass up. Then, of course, is one of my all-time favorites, Sciadopitys verticillata.

The conifer, Japanese umbrella tree (Sciadopitys verticillata)

Indomitable Conifers in Winter

‘Irish Eyes’ Leyland cypress has been in the ground for three winters; this will be its fourth. It’s a beauty with wispy foliage, almost lime-green in color. The first season I wrapped it in burlap. For the second winter, I protected it with stakes and a burlap screen.

When the third winter approached, I wished it “good luck” and did nothing. Each year after spring arrived, ‘Irish Eyes’ came back bigger and even more colorful. Last winter, it lost its top three inches to frost. However, the plant was undeterred. It flourished this past spring and summer.

My conifer confidant, Jon Genereaux, told me to wrap the Japanese umbrella pines (both of which came to my garden via ACS meetings) in burlap. Those two little trees are my 7th and 8th attempts at growing the plant in my garden. Attempt #7 made it through last winter. It was planted behind a giant, sculpted Pinus sylvestris, which I had bare-root planted in 2002. I moved the umbrella pine away from a brick wall which caused it to burn a bit because of reflected, radiant heat. It’s still protected today by its bigger brothers and sisters, as is #8.

The conifer, ‘Blue Ice’ Arizona cypress (Cupressus glabra ‘Blue Ice’)

Protected Planting in Conifers

The idea of “protected planting” has become the basis of my experiment. I use other zone-suitable conifers as wind and sun blocks. Two ‘Thunderhead’ black pines have been happily flourishing and growing nestled among other conifers for three years.

A very large one succumbed to the polar vortex of 2014. It was 7’ tall and magnificent. That winter burned it totally all the way down to the snow coverage. It subsequently went to the burn pile. The two nestled ones are so pretty and have been vigorously growing for three years.

I have left the ones I worry most about until now. ‘Electra Blue’ and ‘Blue Ice’ could become victims if another polar vortex sweeps in. ‘Blue Ice’ is awaiting its second winter. It stands with a very large Abies concolor between it and the southern wind and sun.

Last winter it did suffer some winter burn to its older foliage, but it continues to glow that lovely powdery-blue. ‘Electra Blue’ is really pushing the envelope. Cedrus deodara in Zone 5? I adopted it while protesting its chances with my local nurseryman. Time and Old Man Winter will tell. Fortsetzung folgt, as Martin Luther once said. More to follow in the spring.

The conifer, 'Electra Blue' Deodar cedar (Cedrus deodara ‘Electra Blue’)

Conifer Care of Winter Houseplants

I left cedar of Lebanon second to the last. In The Harper Collection at Hidden Lake Gardens there stands a very large Cedrus libani var. stenacoma. Jack Wikle, former curator of The Harper Collection, tells the story of its first winter as a rough one. It lost all its needles and looked dead. Then came spring. It came back strong and hasn’t wavered since. My stenacoma is protected in my garden, surrounded by other conifers. Winter is the test.

The last conifer out of my zone and in my care is Dacrydium cupressinum. She came to me from the West and lives now as a winter-houseplant until spring comes. “Her” provenance is New Zealand. She could be a “he”, in that the plant is dioecious. It is now living in a moderately heated room with light on every sun angle except South. Its care is delicate. It requires average light and a moist soil.

That all sounds rather labor-intensive, but, until spring comes, winter provides just the right contemplative time to fawn over Dacrydium. Once again, we will have to wait until spring to see if my newest conifer has found a comfortable home.

The conifer, rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum)

Pushing the Envelope with Conifers

Why, you might ask, would I spend time and money trying to fit a square peg into a round hole? It’s the challenge and the desire to rescue conifers and then to test them. I am, after all, on the edge of a change of USDA zones. Our webeditor, Sara Malone, tells me that my Zone 5 is now 6a. That may help the plants that otherwise would not be able to survive in my neck of the woods.

I suspect that some of you have planted conifers that push the envelope in your USDA zone. I would appreciate hearing of both your successes and failures; my greatest and most expensive failure being Araucaria araucana growing indoors, to which my friend Tom Cox said I was “touched” (in the head), meaning “crazy”. Tom, you were right. The monkey puzzle tree succumbed. A three hundred pound disaster!

The conifer, Stenocoma Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani var. stenocoma)

Photographs by Ron Elardo.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

Conifer Winter Damage: Developing Cold-Hardy Cryptomeria japonica

By Web Editor

December 6, 2019

Follow the search for a winter-hardy conifer for the deep south.

The conifer, Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) in close-up view

"I had the honor of receiving one of the two scholarships awarded in 2008 by the ACS. In addition to the scholarship, the Society was gracious enough to support my attending the 2009 National Meeting in Hauppauge, N.Y.; for which I am greatly appreciative to all members.

Between trips to some of the most amazing and historic gardens in the U.S., I was afforded the opportunity to share a portion of the research that I conducted at the University of Georgia Tifton Campus with Dr. John Ruter. The following is a summary of that presentation and discusses an evaluation of Japanese cedar cultivars for performance in USDA Zone 8a as well as development of induced polyploids in an effort to develop a non-winter browning form of cryptomeria." – Ryan Contreras

Conifers in the South

Tifton, Georgia is a hot place; period. It is located in the coastal plain region (USDA Zone 8a) and is strategically located far enough away from both the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean such that it receives little of the moderating effects of either. We experience over 100 days per year at or above 90 °F. However, we also have freezing temperatures and reached a low of 17 °F during the winter of 2008-09. Winter skies are often clear with little cloud cover and low temperatures; a perfect combination for photoinhibition which will be discussed below.

The general dogma has been that most conifers are not adapted to USDA Zone 8a; however, the conifer collection in Tifton is helping to dispel the miscon- ception that conifers can’t be grown in the Deep South. Other collectors such as Ron Determann, Tom Cox, and the late J.C. Raulston also have shown that there are more coniferous options for the south than Leyland cypress.

Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) is one species that has received attention as an alternative for Leyland cypress due to its excellent form, dense foliage for screening, rapid growth, and reduced susceptibility to bagworm infestation. However, as we are all aware, there is no such thing as a perfect plant and Cryptomerias are no exception. One major problem during the winter is that Japanese cedar turns an unattractive reddish-brown color which causes gardeners who are unfamiliar with this characteristic to think they have a dead plant on their hands.

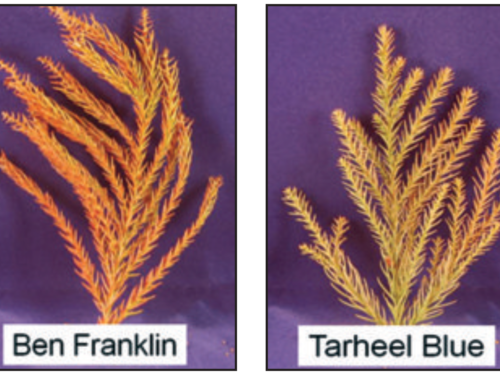

The conifer cultivars 'Ben Franklin’and‘Tarheel Blue’ exhibiting winter browning

Winter Browning in Cryptomeria japonica

Winter browning occurs due to a phenomenon called photoinhibition that takes place under periods of high light and low temperature. Research has shown that browning only occurs in sun-exposed leaves and that the pigment responsible for the off color is the carotenoid rhodoxanthin. Pigments such as rhodoxanthin reduce damage from excess light energy and provide a protection for the photosynthetic apparatus.

Plants have a number of other mechanisms for protection such as reduction of chlorophyll and increasing antioxidant enzyme activity. The latter mode of protection is where we have the greatest opportunity for manipulation and development of new plants. Damage during photoinhibitory conditions occurs because the enzymes in downstream reactions (Calvin Cycle) are slowed due to low temperatures resulting in the production of free radicals.

Free radicals cause oxidative damage and can destroy DNA, proteins, and lipids. Antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), protect plants by interacting with free radicals to ultimately return them water and oxygen. Increased levels of SOD have been shown to reduce damage to the photosynthetic apparatus and tetraploid forms of Japanese cedar were found to have a six fold increase in SOD activity.

‘Radicans’ and var. sinensis do undergo somewhat of a color change, but have amuch better winter presentation

Seeking Non-Winter Browning Mutants

Tetraploids are plants with four sets of chromosomes instead of the “normal” diploid condition of two sets. These individuals were identified in the forest nurseries of Japan by their thickened and twisted leaves and by their non-winter browning character; our trait of interest. Unfortunately, polyploids do not make useful timber trees and have been discarded in favor of individuals that yield more board feet.

At the University of Georgia Tifton Campus we conducted quantitative evaluation of 16 clones of cryptomeria including 15 cultivars and var. sinensis. The goal was to identify superior individuals for the deep south by measuring the amount of chlorophyll and carotenoids and assigning a color rating based on visual observation (1 = brown/red/yellow; 5 = green). Redfire (Phyllosticta aurea) is also a problem on cryptomerias in the Deep South; particularly on slow growing/dwarf forms, and incidence on cultivars was noted.

We also performed experiments to develop tetraploids in hopes of producing a non-winter browning form. Comprehensive results will not be presented here for the sake of brevity; however, a brief description of performance of the 16 taxa will be included followed by findings of the experiments to induce polyploidy. For a more complete description of most taxa included here, see Rouse et al., HortTechnology 10(2):252-266. Synonymy among cultivar names are indicated in parentheses after the cultivar name the plant material was received under.

Two leaves of induced tetraploid (left) developed at the University of Georgia Tifton Campus and diploid (right) Japanese cedar with wild-type leaves

Cryptomeria japonica Cultivars

‘Araucariodes’: Does not handle summer heat well; exhibits substantial branch death. After 11 years in the ground has reached a height of 4.0 m (13.1 ft).

‘Barabit’s Gold’: Yellow foliage form that never turns the attractive golden color in Tifton. Planted in 2006, after two years in ground 2.0 m (6.6 ft).

‘Ben Franklin’: Vigorous growth. Poster child for winter-browning; turns rust- brown. 8.3 m (27.2 ft) after 11 years.

‘Black Dragon’: Approximately 80% dieback due to redfire. Sports readily; must have pure material for propagation. 3.3 m (10.8 ft) after 11 years.

‘UGA5-15’: New selection made by Tom Cox for rapid growth; Tom indicated that it remains green during winter in Canton, Ga. (USDA Zone 7a) and is 16.8 m( 55 ft) after 14 years. Planted in Tifton evaluation in 2008 and has performed as well as the industry standards thus far with no incidence of redfire.

‘Cristata’: Unique cockscomb branches; interior dieback prevalent. 4.0 m (13.1 ft) after 11 years.

‘Gyokruga’ (= ‘Giokumo’, ‘Gyokruyu’): Best performer of the slow growing forms. Remains green in winter with less interior dieback than other slow growing cultivars. 2.5 m (8 ft) after 11 years.

‘Radicans’: Newly planted in 2008; along with ‘Yoshino’ it has become the industry standard in southeast U.S. Slower grow- ing than ‘Yoshino’ but remains greener during winter.

‘Rasen’(= ’Spiralis’, ‘Granny’s Ringlets’): Novel twisted foliage, very dark green foliage in summer. Intermediate growth rate. 6.1 m (20 ft) after 11 years.

‘Sekkan’: Yellow foliage form that has a chlorotic appearance in summer and is brownish in winter. 5.6 m (18.3 ft) after 11 years.

‘Tansu’: Moderate growth rate with short, stiff leaves; shrub-like appearance. Dark green in summer; fair winter appearance with limited interior dieback and redfire. 5.5 m (18 ft) after 11 years.

‘Tarheel Blue’: Excellent form and attrac- tive blue foliage in summer; poor winter appearance. 8.3 m (27.2 ft) after 11 years.

‘Tarheel Plum’: Newly added to the trials; thus far has not been impressive. Does not develop the reported purplish foliage in Tifton.

var. sinensis: Similar to ‘Yoshino’ with longer leaves and more open growth; does well in Tifton. Has ground layered in our trials. 6.4 m (21 ft) after 11 years.

‘Yaku’: Only uppermost branches are surviving due to redfire. 6.2 m (20.3 ft) after 11 years.

‘Yoshino’: Industry standard for fast growing, conical form. 8.2 m (26.9 ft) after 11 years.

Conifer Trial Results for Winter Browning

From the trials in Tifton the recommended cultivars for USDA Zone 8a are ‘Gyokruga’, ‘Yoshino’, and var. sinensis. ‘Radicans’ has remained greener than many cultivars; however, it appears to be highly susceptible to redfire. It has only been in our trials for two years and is already showing a large amount of dieback. ‘Tansu’ also has utility as a moderately slow growing form, although winter color is not as desirable as ‘Gyokruga’ and the form is not as good.

Other slow growing cultivars have exhibited extensive branch death due to redfire. UGA5-15, the selection from Cox Arboretum and Gardens, has also shown potential but requires additional evaluation to determine if its performance in Zone 8a will be similar to that seen at Tom’s. Other cultivars that were planted in 1997, but died prior to the current evaluation due to redfire include ‘Rein’s Dense Jade’, ‘Ikari’, ‘Globosa’, and ‘Vilmoriana’.

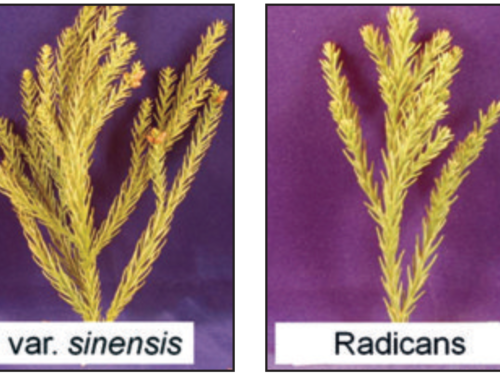

Range of conifer habit and growth rate exhibited by induced tetraploid Japanese cedars developed at the University of Georgia Tifton Campus

Developing an Evergreen Evergreen

To induce polyploidy, nine different experiments were conducted. These experiments included treating stem cuttings, seed, and seedlings with various combi- nations of colchicine, oryzalin (Surflan®), DMSO (an adjuvant), and various surfactants. After numerous ineffective treatments, a long-term treatment (30 days) of oryzalin in combination with a surfactant was applied to approximately 600 seedlings at the cotyledon stage.

Two-hundred thirty-seven seedlings that had thicker, twisted needles were transplanted and evaluated for induced polyploidy. Of these seedlings, 219 had cells that were tetraploid, 197 of which were solid tetraploids. Five months after treatment, a subset of the tetraploids were reevaluated and found to contain only tetraploid cells; indicating that over that time they were stable. However, evaluation over numerous years is necessary to determine their long-term stability and ornamental potential.

Overall, tetraploids exhibit morphology similar to previous reports, including thicker and twisted needles than the wild-type; however, there was a range of habit and growth rate among them. Ultimately, we hope that this results in a series of various forms from the very dwarf, to vigorous specimens that remain green in winter and help promote what a great plant Japanese cedar is.

Text and photographs by Ryan Contreras and John Ruter.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

By Web Editor

February 15, 2020

Plan your next conifer adventure at one of ACS' Reference Garden near you.

When two groups work together to benefit both partners, it’s a beautiful thing. That beautiful thing is blossoming between public gardens and American Conifer Society members through our Reference Garden Program.

The ACS has a mission to promote, propagate and conserve conifers and to educate the public about them. Public gardens have multiple missions, but most include conservation of special plant material, horticultural display and education of the public.

By joining together, ACS members and their local public gardens are helping each other carry out their missions while enjoying themselves as they do.

So, what exactly is a Reference Garden?

The idea comes as a way to offer a “point of reference” for conifers that grow locally. It is a means for our members to see and compare larger numbers and specimens of conifers. For ACS purposes, the garden must be an institutional ACS member,

open to the public and must have a minimum number and variety of well labeled conifers in its collection. Other requirements include sponsorship by at least two ACS members.

In return, public gardens have the opportunity to develop a closer

relationship with their garden sponsors and local ACS members, to expand the avenues of public relations between the two groups, and to apply for conifer related grants from their regional ACS. This regional money comes directly from our annual regional

meetings, and goes back into the regional gardens. Each region has some room to focus on its needs from this program, but all support the conifer related outreach that these public gardens give us.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

By Gerry Donaldson

February 20, 2020

Learn more about oak wilt disease, its symptoms, and how to prevent its spread.

Symptoms of Oak Wilt Disease

Oak wilt fungus grows quickly within infected red oaks and plugs

the xylem tissues, causing death of the tree in as little as two months. In some case, death can take up to a year or more. First symptoms in red oak are wilting leaves that turn dull green or brown and curl around the midrib, often mimicking drought

stress.

Leaves will drop from the tree, usually starting with branch tips. Even what appear to be healthy green leaves can be shed. Dark streaking under the bark is often found in red oaks that have recently shown symptoms where the fungus has

plugged the xylem tissues. If collecting samples for submission to a diagnostic lab, freshly cut twigs or small branches 15 to 20 centimeters long (approx. 6 to 8 inches) should be placed in zipper style plastic bags and kept cool until examined by

a diagnostician.

Oak Wilt Disease Spread by Spores and Beetles

The oak wilt fungus, Ceratocystis fagacerum, can overwinter under the bark of living trees and as fungus

mats under the bark on dead trees. These fungus mats can grow and cause the bark to split and emit an odor sometimes described as smelling like apple cider.

A variety of beetles feeds on the sap and/or fungus mats, picking up spores that

then get spread to other trees during feeding or egg-laying. From early spring to mid-July, the fungal spores are spread by beetles from infected trees to other trees, especially trees that have been wounded or pruned.

Do not prune once

spring temperatures reach 50 degrees Fahrenheit, as a few fifty degree days can get beetles moving and cause the fungus in infected trees to form fruiting structures, leading to the spread. Pruning can resume in mid to late July.

In the

event a tree is wounded through pruning, equipment damage, another tree falling and damaging bark, or climbing with spurs, immediately paint the damaged area with tree-wound paint or latex paint. That will help keep beetles from feeding on the sap

and introducing spores to the damaged tree.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

Conifer Bonsai Shaping

By Jack Christiansen

September 20, 2019

Learn about the art of wiring conifer bonsai. This is part 1 of the author's guide on shaping and caring for bonsai. Click here to read part 2.

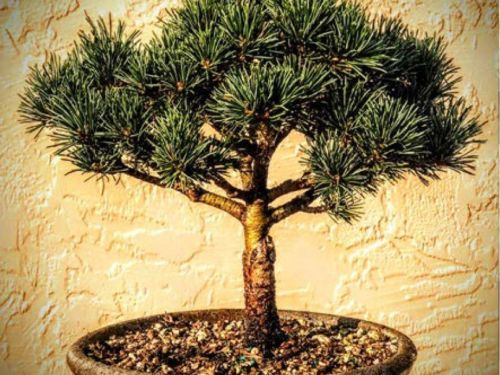

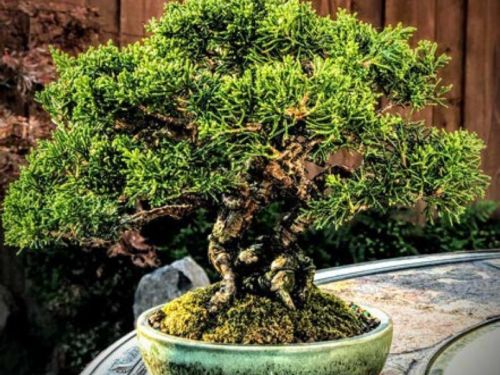

A rock-planted conifer Juniperus chinensis 'San Jose' that is wind-influenced with dead wood features

I’ve been asked many times by newcomers to bonsai, “how does one start shaping or styling one’s first tree?” Putting wire on a tree and bending it to try and make it interesting can be rather intimidating for beginners. It is best to have a set of clear ideas going into the tree’s development.

With professional bonsai, styling a tree can get very complicated. The Japanese, over time, have developed many rules, or standards, that they felt were important. Everything has been judged according to those principles. Today, those rules are no longer the only standard, and bonsai is certainly more flexible for the hobbyist.

Choosing your Conifer Bonsai

Many trees in nature give us great ideas for how we would like to style our bonsai. You chose a tree because it speaks to you in some fashion, or maybe you saw a tree in nature and would like to duplicate it in miniature. That’s why I recommend that once you have your tree, study its structure, determine its strengths and weaknesses.

To find out more about finding plants, either to start as bonsai or to add to an existing collection of bonsai, read Jack Christiansen's Looking for the Perfect Bonsai.

Often, it is best to do this over a period of time, going back and forth to it, to gain new perspectives. Once you have a basic idea, sketch a few drawings to help you form ideas for how you would like to proceed.

Not all bonsai are stylized after trees in nature. In fact, many professional bonsai trees today take on bizarre forms, in which the artist expresses a unique style. Then there are trees that already have a shape or structure, crying out to be styled in just a certain way. You need to be attuned to all of these opportunities.

A great example of a nice little conifer that has never been wired. Pinus parviflora ‘Regenhold Broom’

Your first tree: observe and envision

Long smooth curves and movements on trees can be very appealing to the viewer’s eye. Strong structural movements can reflect extreme weather conditions that a tree might endure in its natural environment.

Observing nature provides many clues. For instance, a maple (Acer palmatum) will never have deadwood features like a juniper or a pine would have.

Keep in mind that your own self-expression and vision will guide what your tree eventually becomes. You don’t need to start with a bristlecone pine with all its strong features and dead wood. So long as it satisfies your own expectations, you have succeeded.

Your first tools: where to get started

There are many companies that offer bonsai supplies online. Local nurseries may offer bonsai starter kits. There may be bonsai clubs in your area that can refer you to preferred suppliers. Bonsai tools come in various prices, but can be more expensive than hardware tools.

An inexpensive set of three tools is all one really needs to get started. Wire cutters, pruning scissors, and a concave branch cutter will handle most of your bonsai requirements.

Once you have a plan for styling and the basic materials for your tree’s development, it’s time to cut back lengthy branches and begin the wiring process.

Juniperus chinensis ‘Shimpaku kishu’ never wired and right out of a 4-inch pot

First, cut away unwanted branches around the trunk and any dead or weak branches that clutter your pathway. Keep in mind that, in order to apply the wire to the branches and trunk, there must be a clear path so that you can systematically wrap the wire.

Using wire allows us to train, shape, style, and, ultimately, affords us the artistic ability to depict movement and stability.

Bonsai wire comes in two types, copper and aluminum. Annealed copper wire is used for most conifers, and aluminum wire is used for deciduous trees. If you can get only one type, either will work. Wire comes in rolls of various diameters.

Choosing Conifer Bonsai Tools and Wires

Make sure that you choose wire large enough in diameter to have the strength to hold the bends you want in the branches to be wired. Having three rolls of various diameters will take care of most of your needs.

It is necessary to cut the wire at least one-third longer than the length of the surface to be wired. Start by sticking one end of the wire down into the soil next to the trunk line, pushing it into the soil at the angle you’ll be spiraling the trunk. Two inches is usually enough to secure the wire into the soil. Then start wrapping the wire around the trunk at about a 45° angle, bypassing the branches and spacing the wire evenly all the way up the trunk.

Conifer bonsai tools and wire

Remember, care is needed when applying wire to the surface of your tree. Don’t strangle the branch with the wire, but also don’t loop the wire too loosely either. Simply wrap it carefully onto the tree’s surface, looping it around side branches at about a 45° angle.

When wiring your branches, always connect two branches at a time; one branch will be a support for the other branch after coming off the trunk line. It is helpful to practice this on a dead branch before you tackle your bonsai.

I highly recommend YouTube videos such as How To Bonsai - Basic Wiring Technique, or for a more advanced demonstration, Bonsai Detail Wiring by Ryan Neil, in order to understand the proper way to wire a tree. Learning to wire the entire tree properly is an art in itself. The more you practice, the more comfortable you’ll be with the procedure, and your tree will be happier for it.

Wiring of the trunk at 45° angle (left); wire inserted 2” into the soil (right)

Once you have wired the needed parts of the tree, it is time to start bending and positioning the branches into the desired locations. Take care as tree branches can be brittle, especially at certain times of the year. Conifers can be more forgiving and flexible than hardwoods, but you’ll need to hold the trunk with one hand and gently apply pressure to the branch with the other.

If you hear any cracking, release the pressure, gently and gradually flexing the branch back and forth to increase flexibility. Start bending again, but go slowly and carefully. If the cambium layer of the branch is exposed due to cracking, it will have to be sealed.

Common Conifer Bonsai Mistakes

A common beginner mistake is to bend wired branches over and over again until the vascular sytem is imparied. This leaves the branch lifeless, and removal of the dead branch will create an open space in that area of the tree. This is a good reason to have a firm plan for positioning and styling before bending.

It is important to check periodically that the wire isn’t cutting into the branches, as spring and summer growth causes branch expansion. If necessary, cut off the old wire and rewire to prevent unwanted marks.

Photographs by Jack Christiansen.

Jack is an ACS member, an avid bonsai-enthusiast and bonsai-creator. His garden is an excellent example of creative design and the integration of bonsai into the garden. His knowledge and photographic skills are well-known and widely appreciated. He lives in San Jose, California. Over the years, Jack has been a valued contributor to the CQ.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 8, 2023

|

By Web Editor

February 7, 2020

Find out the ways to protect your conifers from deer damages by nibbling does and rubbing bucks.

The conifer, Sekkan Sugi Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica ‘Sekkan-sugi,' center) under a canopy of coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)

Our gardens at Harmony Woods are nestled into a cathedral of Sequoia sempervirens. To the best of our knowledge, the coast from northern California to southwest Oregon is the only place where the species is found in nature. Under the canopy of the redwoods, we feature over 300 conifer species enhanced by a vast array of plants gracing over twenty beds. By the very nature of the name “Harmony Woods”, we imply an attitude of living with nature through gentle guidance.

Deer emerge tentatively from our forest, a doe with two fawns at one time, or two bucks at another. They are alert, but calmly pursue their need of finding food and sometimes resting in the sun on our green. We delight in their presence. Most conifers on our property appear deer proof. Some new growth has been nibbled, but frankly my husband Bob and I can’t recall the names of those few affected.

The conifer, Sekkan Sugi Japanese cedar (center) with Picea abies ‘Pendula’ in front as ground cover. Tall Picea orientalis ‘Nana’ is to the left with Pinus uncinata ‘Berhal #4 WB’ below and Taxus baccata ‘Standishi’ at center right

Living with Nature

One key to our success in living with the deer is to plant genera which are not attractive to them. Several months ago I looked up and saw a lovely doe under our plum tree, nibbling the fallen leaves from the tops of the plants underneath. Her lips were so supple, her tongue lifting each leaf with a beautiful grace so that the plants below were not affected. I imagined how delicious the leaves must be to her. She was the perfect gardener.

The conifers under the plum tree include: Abies procera ‘Glauca’, Cedrus deodora ‘Divinely Blue’, Cryptomeria japonica ‘Compressa’, Picea glauca ‘Elf’ and ‘Haal’ (Alberta Blue), as well as Picea pungens ‘Glauca Prostrata’. In addition, there are Rhododendron, Helleborus orientalis, Darmera peltata, the grass; Hakonechloa macra, the ferns; Pyrrosia lingua, and Sarcococca. Most plants were purchased locally.

The large conifer, rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum) from New Zealand under a redwood canopy

Ways to Keep Deers Away from Conifer Trees

For plants the deer love, our secret is to guide them away with a product called “Liquid Fence Deer and Rabbit Repellent," which is readily available in our local nurseries. The ingredients are harmless and although we cannot smell the odor shortly after spraying, the deer find it offensive.Bob does the rounds every few weeks.

The only deer fencing we have on the property is for the perennial garden and we used a black polypropylene mesh fencing material affixed to redwood posts. Our fencing company purchased the product from Benner’s Gardens in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. It is sturdy and practically invisible. Although we know the fence exists, the plants around it and the gardens beyond catch the eye. Just remember to keep the gates closed!

For the bucks who love to remove the soft velvet from their antlers in late summer by rubbing against tree trunks and often damaging the circle of cambium, we use tall semicircular plant supports sold in many gardening catalogues. Join two together with some twine and you have a temporary fix. The message the doe, a beautiful creature of nature, gives to us is that with well-chosen plants and a few products to guide, a gardener can enjoy the beauty of both the plants and the deer. For us, that is a bonus to treasure and adds a glow to the seasons.

The conifers, Cryptomeria japonica ‘Birodo-sugi’ (left front), Abies procera ‘Glauca Prostrata’ (center front), Picea glauca on the right with Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Pygmaea Aurescens’ underneath Cornus capitata ‘Mountain Moon’ behind the fence

Text by Judy Appel Mathey. Photos by Bob Mathey.

Judy and Bob Mathey garden in a Mediterranean type eco-climate which is particularly suitable to growing tender leaf plants. They avidly collect conifers as well as Rhododendron species, ferns and maples.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

CR Director

CR Director WR Director

WR Director WR President

WR President ACS Secretary

ACS Secretary ACS President

ACS President CR President

CR President ACS Treasurer

ACS Treasurer SER Director

SER Director