|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 15, 2023

|

Drip Irrigation System for your Garden

By Robin Tower

September 27, 2019

Find out how to install your own drip irrigation system for your conifer garden.

Get ideas on installing a drip irrigation system in your garden

First I should explain that I am not an irrigation expert. What follows are my observations from my own experience with drip irrigation. I expect that when you think of a drip irrigation system you think of neat orderly rows of tomatoes or beans. It’s hard to imagine it applied to a meandering, random set of conifers in a large area. But drip irrigation works just as well in that situation!

The advantages of watering with drip as opposed to sprinklers or buckets are several. A large amount of the water delivered through a sprinkler is either lost to evaporation or lands between plants, thus promoting the growth of weeds. Buckets are back-breaking, and deliver the water too rapidly, so that much of it is wasted. A drip is like a fine rain soaking into the root system over a set time, perhaps an hour or two. Therefore, it is both less labor intensive, and much more efficient.

Sketching the Drip Irrigation System Out

Figure 1 showing a drip irrigation system of a garden

To get your project started you will need a rough sketch of the area to be watered. It might look something like Figure 1. Seeing the property from the air as it were, allows you to analyze how it might best have watered delivered through pipes.

In Figure 1, I show a display bed of conifers and perhaps other plant material that is about 50 ft. long and of varying depth. It contains about 42 plants of different sizes.

Secondly, you will need to have an idea of how many gallons per hour your water source can supply (its flow). This is an easy job – turn the hose on and fill a 5 gallon bucket. How much time did it take? Mine took about 56 seconds. So it will supply about 11.2 gallons every second (So, it will supply one gallon every 11.2 seconds, or 321 gallons per hour.) This number will determine how many plants you can water at one time.

The emitters you will use to supply water to each bush will put out 1 gallon per hour. I usually use one emitter on a bush less that one inch in caliper, and increase by one emitter for every caliper. So, a bush with a trunk of 3 inches in diameter would have 3 emitters, and get 3 gallons of water an hour.

Determining the Pressure in the Drip Irrigation System

The third piece of useful information you will need is the amount of PSI (pounds per square inch) of water pressure your system provides. You can buy a gauge to measure this quite inexpensively from an irrigation supplier. Screw it onto the end of a hose, and when you turn the water on, and voila! Your pressure is measured. I use 2 water sources, my own well and pump, and a municipal source.

I found that the municipal system had a lot more pressure (about 45 PSI) than my well (15 PSI). Typically, the water tubing which delivers the water to the plant is designed only to handle a maximum of 30 PSI – so, if your source is higher than that, you will need a pressure regulator to reduce the water pressure going into the system.

Assembling the Drip Irrigation System

Figure 2 showing the garden's main line connected to the water source of the drip irrigation system

Now that you have gathered information, it is time to put it all together. Draw a line (the main line) connecting in the most logical order possible your conifers or other trees to be watered. (Figure 2) The line does NOT have to run from one to the next, but simply near them. The start of the line should be near your water source.

With any luck, it will slope downward from there towards the end of the line, although this is not completely necessary. You can plan on more than one main line and connect them with a T or Y connector. However, if your flow as measured above is 300 GPH, then remember that you can only put 300 emitters on one main line. You will use hose connector fttings for the beginning and end of the line.

Next we will get the water to the bushes from the main line. A branch line is used for this, usually ¼ inch tubing. The tubing connects to the main line with a ¼ inch transfer barb. The emitter fits into the ¼ inch tubing connecting with its own transfer barb on the emitter.

Emitters and Tubes for the Irrigation System

Figure 3 demonstrating the position of emitters of a drip irrigation system in the garden

There are several diferent types of emitters available. What you MUST have is a pressure-compensating emitter. These will ensure that you get the same amount of water delivered through each emitter, even if your terrain is uneven. I have used the CETA in-line emitters. These come on stakes so that they can be put securely in the ground near the root ball of the plant. They can be used in tandem, so that you can put several around the base of a tree (See Figure 3).

Since I have 42 plants, and need to use an average of 3 emitters per plant in this imaginary garden, I am well within the maximum of 321 emitters per line. If I had more plants, or more areas to water, I would make each area a separate zone, with a separate connection to the water source.

Final Touches around the Conifer Garden

You will want to secure the main line to the ground with landscape staples. At some point, the main line should be covered with mulch or buried a few inches below ground by trenching. This procedure will keep the plastic from degrading in the sun. It is not necessary to do this immediately; in fact, I have waited a year to do mine. That way, if there is a problem with emitter placement or a misplaced hole punched, I can spot it and correct it without digging up the line.

Lastly, we will connect our main line to a water source. The connections between main lines are all hose threaded, so that there is no real plumbing involved. Simply push the female hose end connector into the main line, and you are ready to hook up the system!

However, there are several pieces and they need to be put together in the correct order. Closest to the water source, you will need a screen flter, particularly if you are using well water. If you are pumping from a pond you may need a heavier duty flter perhaps a Disc flter. Debris in the line will clog the emitters and should be avoided at all costs!

Other Accessories for a Drip Irrigation System

Next in the order is the PSI regulator. Then the mainline tubing is connected with a female hose start. (See Figure 4), and be sure to put end caps on each main line, or the water will simply flow right on through! Two important notes: I found that punching holes in the main-line tubing did not work well after the tubing had warmed in the sun. The punch merely bent the tubing without leaving a clean hole. You will want to purchase a pack of goof plugs in case this happens to you. They are useful as well to stop up a hole you may punch inadvertently.

Lastly, don’t forget to drain your lines and put away the water source connectors before the frst frost. Like any other plumbing, freezing under pressure will cause pipes to burst. I have found draining the lines to be relatively easy. I just take of the end caps and store for the winter.

Figure 4 showing the drip irrigation system's mainline tubing and female hose start

A Worthwhile Conifer Garden Project

The cost of the system as pictured in Figure 2, with an average of 3 emitters per plant will be around $200. I would estimate that it would take 8 – 10 hours to install, depending on how handy you are with the hole-punch! This entire procedure may sound time-consuming, and it is! But it is much easier than delivering water by hand over acres every summer.

Once I set mine up, I connected it to the water source with a timer. Now, when I want to water my conifers, I set the timer for an hour or two, go about my business, and return when I can. I can then put the water on another zone, set the timer, and walk away.

I will say that before I turn my back I usually look around to make sure there are no geysers in the watering zone. If I see a large water spout, one of the branch lines has usually become disconnected from the mainline. I usually blame this phenomenon on one of the dogs tripping over it while chasing a ball. Makes more sense than that I might have dislodged it! It’s a simple matter to reattach, but it must be done so that the emitters can do their jobs!

There is a lot more information concerning drip irrigation on the Internet: diagrams, YouTube tutorials, and so forth. In my opinion, it is well worth the time and money invested in drip irrigation to take care of my wonderful conifers!

Photograph by NeONBRAND; illustrations by Jason Smart, Smarty Design Co.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 15, 2023

|

Conifer Fasciation with Cryptomeria japonica ‘Cristata’

By Ronald Elardo

September 6, 2019

Learn about the unique phenomenon of conifer cresting.

Fasciation in ‘Cristata’ refers to the banded or bundled growth at the tips of its branches

Dan Gurney submitted the photo of ‘Cristata’ to the Conifer Quarterly. You would agree that it is most intriguing. When I looked up Cryptomeria japonica ‘Cristata’ (cristate Japanese cedar) in the ACS conifer database, what I found spurred me to investigate the possible reasons for this phenomenon, known as cristation, or fasciation.

The cultivar name ‘Cristata’ comes from the Latin adjective cristatus which, in turn, is related to fasciate. The noun, fasciation, describes the banded or bundled growth at the tips of the branches of a plant. Cristate means having a crest-shape, like the cockscomb on the head of a rooster.

Scientists believe that cristation, or fasciation, results in the tip of the branch growing outward, rather than growing farther along the stem. They attribute this fan-shaped growth to hormonal imbalance, insects, diseases, or physical injury to the plant.

A Natural Occurrence in Conifers

The strange growth is most likely caused by phytoplasma, which are bacterial parasites of the phloem tissue and of the insect vectors involved in plant-to-plant transmissions. The fan-shaped protuberance appears on many genera of plants: cacti, roses, and beefsteak tomatoes, to name but a few.

As a consequence, since cristation is a cellular deviation, it may be the result of a genetic predisposition inherent in the plant, which causes division of growth and consequently that characteristic spreading-out at the tip of the branch. It would be interesting to hear from you, the membership, on this subject. In the meantime, a Google search will yield an array of beautiful pictures of plants with fasciation and cristation.

A Hidden Conifer Gem in Woodinville

Dan Gurney reported that this particular cristate Japanese cedar is 50–60 years old and 50-feet tall. It has been growing in Woodinville, Washington, 20 miles northeast of Seattle at the JM Cellars Winery of Peggy and John Bigelow. The previous owners of the winery, Jan and Smitty Smith, were conifer collectors.

In the ACS conifer database, one can see an excellent closeup of the cockscomb-like growth on a ‘Cristata’ specimen at the Cox Arboretum and Gardens in Canton, Georgia.

Photograph by Dan Gurney.

Dan Gurney is co-owner of Gardening Artist with his wife, Mary Warren. They reside in Seattle.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Thursday, June 15, 2023

|

How to Care for a Conifer Reference Garden

By Mary Coyne

November 2, 2019

Dr. Mary Coyne speaks on the challenges and rewards of watching over the Wellesley College Conifer Reference Garden.

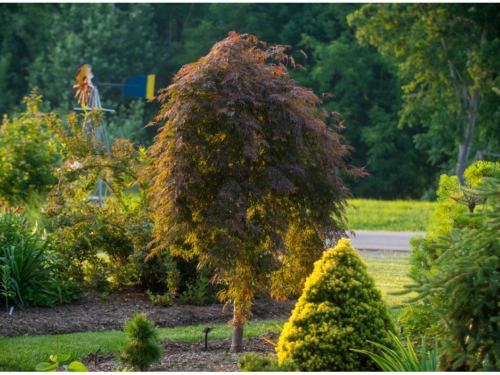

A view of by the Conifer Reference Garden. Photograph by Wellesley College Horticulturist, David Sommers

Passersby say, “It looks great!” As of 10 years I ago I thought it would always “look great,” but I had a lot to learn. It seemed like an easy project – build a wall, bring in new soil, pick out some plants, plant the dwarf and miniature trees, stand back and watch them grow. Nothing to it.

Ten years later at the Wellesley College Conifer Reference Garden, I know better and I thought that some of my experiences might be helpful and possibly amusing to those in the know. The Wellesley Conifer Reference Garden contains mostly dwarf and miniature conifers and is located on a slight upward slope extending back from a 3-foot high wall, running about 60 feet in length.

Watering Solutions for a Conifer Reference Garden

Мy first problem was water. I had insisted on running two water lines to the top of the embankment above the wall, but setting out hoses and sprinklers was taking too much time for the greenhouse personnel.

So, I considered a drip hose for the area and found a wholesale dealer for RainBird equipment nearby. The dealer measured the water pressure for the extensive lines and determined that because the area was so large, it had to be divided into three sections. The downside of this arrangement is that each section took about 5 hours to water and often the personnel went home and forgot to turn the water off.

To solve this problem, I installed three elevated spray heads so the workers could see if the water was still on. Newly planted trees needed more frequent watering, a task given to the summer student interns. I oversee and maintain this garden mostly by myself with the help of intermittent volunteers, but since I am away most of the summer, I must depend on others to follow through with watering.

Yucca sprouts in the Wellesley College Conifer Reference Garden. Photograph by Dr. Mary Coyne

Yucca Control within a Conifer Reference Garden

One of the original plants scattered across the dry embankment before the area was rescued for a conifer garden, was a yucca. About a month after it was removed, I noticed some shoots erupting in the area. Since the area was unplanted, I dug down about 2-3 feet and uncovered a massive root about 3 inches in diameter and 18 inches long. I was impressed and felt relieved that I had solved the problem.

Ten years later I am still fighting that yucca. Sprouts began appearing again and were moving slowly along the planting bed. Stories on Google were not encouraging, but I finally followed what appeared to be a successful procedure. I let one plant grow up somewhat, clipping off all the others. I wrapped the leaves of this plant with cotton batting soaked in RoundUp, bent the leaves over into a stainless-steel pan with more Roundup and sealed it with plastic.

One month later, the plant was still alive! Not good. A year ago, I let another sprout grow that had popped up outside the garden, hoping that all the plant’s energy would go there and the other small sprigs would die out. It seemed like this was working. But last summer there were sprouts again. I have a life-long job snipping yucca sprouts!

Sawfly larvae munching on Pinus x densithunbergii ‘Jane Kluis’ in the Wellesley College Conifer Reference Garden. Photograph by David Sommers

Managing Sawfly Populations in a Conifer Reference Garden

A good friend of mine in the American Conifer Society always told me not to buy two-needle pines, but never said why. Now I know why. Along the stairway through the garden there were four Pinus x densithunbergii ‘Jane Kluis’ which were growing quite well.

One day one of the greenhouse personnel brought me over for a look at the front plant. Needles were missing and on closer inspection, I saw that it was covered with sawfly larvae. We grabbed our gloves and pulled them off into a bucket of soapy water.

This happened each year. Last year the other three trees had to be replaced as they were in bad shape even though we had been pulling larvae off them each year. Down at the other end of the garden, I also found a dead, chewed-up Pinus banksiana, another two-needle pine. Two of my replacements along the stairway were Pinus heldreichii ‘Banderica‘, a two-needle pine.

Google searches indicated that this pine is not a primary target, and another in the garden is good so far. The Botanic Gardens is a pesticide-free environment, so we’ll see. However, our very dry summer of last year took its toll on the three replacements in spite of assiduous watering.

Adding Variety to your Conifer Reference Garden

The Reference Garden has about 76 living conifers, composed of 18 genera including Ginkgo and Ephedra and several species of Chamaecyparis, Juniperus, Picea, and Pinus. Over the nine years, I have had to replace about 37 trees, either because they had died over the winter (23%), or they were not in good enough display condition (10%). I have two holding areas for replacements, one at the College and another at home where I can watch them more closely. Several at home are recovering patients which may eventually be replanted. It pays to deal in dwarfs and miniatures!

The garden is on a major pathway for faculty, staff and students entering the Science Center, and the conifers provide good winter interest. To introduce a little color for both spring and fall, I have interplanted the area with spring bulbs, ephemerals, and perennials as well as several fall bulbs and rock garden plants in the scree.

The choice of bulbs include

- Narcissus bulbocodium conspicuous

- Trillium grandiflorum and T. nivale

These, as well as wild tulips, has outwitted the chipmunks so far, but they continuously burrow in and around the stone wall, and some bulbs do disappear.

Rock garden plants have variable survival rates so there are always replacements, and some have had to be removed completely because they turned out to be invasive. In the last couple of years, I have also started a couple of hypertufa troughs with miniature conifers and placed them in a protected area.

I am concerned that they might easily be transported away so I keep them out of the main pathway. Extra additions, of course, make more work, but they do make the garden more interesting.

Routine Tasks at a Conifer Reference Garden

Each conifer receives a professional label which has a black background with white printing. Over the winter, there are always a few labels that disconnect from their stem and must be found, cleaned, and reattached with superglue (my solution).

Even the Reference Garden sign needed such repair, probably because children love to walk along the wall and may have knocked against it. New conifers and herbaceous plants are hand-labeled; many labels are missing by spring and are also replaced.

Every other year new mulch is added to the garden, but, because there is a slight slope down to the wall, the mulch usually accumulates at the bottom by the end of the winter. This necessitates cleaning out around all the conifers in the spring so the trunks are not submerged in piles of mulch.

Replacements, watering, and mulch all require funds, and grants from the Conifer Society have supported the conifer related costs. Wellesley College Botanic Gardens provides additional funds for the non-conifer plants.

Map of Wellesley College Conifer Reference Garden. Screen shot of map in ESRI Collector App by Dr. Mary Coyne

GIS Technology and Conifer Reference Gardens

Being a Type-A personality I wanted to keep track of all the plantings: their location, health, and growth rates. I started by mapping the Reference Garden with a CAD program with layers for conifers, bulbs, and herbaceous plants.

However, once the College installed a server for ArcGIS (GIS stands for geographic information systems), I mapped out the Reference Garden and added it to an archived database for all the Botanic Gardens trees. A new Collector app for ArcGIS now lets me do an annual inventory of the trees in the Reference Garden using my iPad or Phone.

These data are connected to each tree in the ArcGIS Map and include height, width, health, presence of label, comments on work to be done, and a photo. The mapping allows me to assess where my greatest losses of plants occur, which species have survival problems, as well as growth rates.

Anyone interested in pursuing the use of ArcGIS for mapping gardens should go online to American Public Gardens GIS website and Alliance for Public Gardens GIS for further information and for access to a GIS template for public gardens.

The Rewards of Watching a Conifer Garden Grow

As a retiree, I have found that working in the garden provides a great social payback. On weekends, I interact with local and international visitors, and during the week I often am called upon to give an extemporaneous presentation to student groups at all educational levels.

College staff and faculty are always passing by and remark how much they enjoy seeing what is growing and blooming. It is satisfying to realize how so many people enjoy the garden. As a long-time gardener of perennial plants, I should have realized that keeping up a Reference Garden would be work. However, I never realized that, in addition to weeding, there would be so many other annual jobs.

How am I going to convince someone to eventually replace me? Maybe they will enjoy it as much as I do.

Dr. Mary Coyne is Professor Emerita at Wellesley College. She may be contacted at [email protected].

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

|

Using Art and Math in Garden Design

By Mary Warren

March 13, 2021

Using art and math to create a garden design might seem like artificially superimposing incompatible sets of rules on plant placement in garden beds. However, in concert, art and math can actually provide good mechanics for building a garden that will be a joy to behold. In this article, the experienced and the hobby gardener alike will find suggestions for a successful layout that will also aid in the best plant choices, all based on artistic and mathematical principles.

Coulter’s pinecone

To begin, one doesn’t have far to look to find a planting grid. Nature provides a few. The structure of the fronds of a fern or the scales of the Coulter’s pine (Pinus coulteri) can suggest a garden diagram. Follow the downward spiral of the cone’s scales or the fern’s unfurled fronds, and a three-dimensional, conical display emerges. If plants are placed to mimic the swirl, with attention paid to the distance between plants, the result is that each plant is simultaneously visible and also contributes to the entire scene. When painting in oils, this layering is referred to as working lean to fat, building pigments from the bottom layers up and across the canvas. When applied, this principle creates a garden with many levels. The garden becomes a living painting as its plants layer up and across the bed.

Logarithmic spiral.

Gardeners who choose the pattern of the scales of the Coulter’s pinecone or the furls of the fiddlehead fern are actually using what the mathematicians dubbed “The Golden Ratio”. To put it simply, the gardener must give plants space, according to growth rates, so that they don’t spoil their neighbors by growing into them. One can find conifer growth rates and sizes in the American Conifer Society’s Conifer Database (conifersociety.org). Other plant specifications are available on the Internet. Knowing how large plants will get assists in choosing the right ones for the space the garden affords.

In selecting plants for the garden, color, texture, and shape provide visual stimuli, evoking a sense of beauty that is unique to each person. For one gardener, the arms of Cupressus nootkatensis ‘Green Arrow’ (Green Arrow Nootka cypress) might appear too zigzagged and visually disruptive. For another, ‘Green Arrow’ symbolizes a skyward motion, a reaching-up, like an arrow shot into the sky. Another gardener might prefer more conventionally shaped conifers like Picea glauca var. albertiana ‘Conica’ (Dwarf Alberta spruce), with its classic Christmas tree shape. Regardless, the choice of plants expresses the gardener’s individuality and personal vision.

‘Green Arrow’. Photo by Ron Elardo

In addition to the proportions suggested by the Golden Ratio, other possible bed designs can be inspired by both art and math. Buddhist mandalas, for example, combine both art and math and are meant to portray perfection. A mandala can be simple or complex. A Google search will yield a plethora of examples. From Western art, there is an even simpler mandala, based on Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, man within a circle within a square, the so-called “squaring of the circle” (Carl Gustav Jung, Symbols of Transformation). From my design education and experience, modifying the square shape of this model to create a rectangular-shaped bed affords the gardener a much more flexible layout plan.

Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

The ancient Greeks applied “golden/sacred numbers” in the creation of the great architectural works they dedicated to their gods. The mathematically precise, rectangular spaces between the columns in the Temple of Athena Nike, at the top of the Acropolis in Athens, can be copied on a smaller scale in the construction of garden beds. Those rectangular shapes can accommodate more easily even or odd numbers of plants than square beds can. Avoid beds planted in rows. They lose dynamic energy and look like a production nursery. Lean to fat planting, as described above, produces a soft and relaxed reaction as the eye begins at the top of the design, pans downward to a flared-out base, and then around the bed back up to the top.

Columns of the Temple of Athena Nike.

A fundamental rule in sketching and painting is to refrain from working solely from one corner outward. Gardeners should shape the garden from all directions simultaneously. They should engage with the entire planting area, in the same way that a tree is pruned aesthetically. The tree is simultaneously viewed from all angles. Gardeners should strive for the best possible three-dimensional look, recognizing that plants will inevitably steer their own way. Height, transparency, density, and color may require particular placement for best effect.

One last consideration is the inclusion of different soils, rock formations, structures, and figurines into the garden. These elements may require rethinking plant placements, while maintaining balance and the impact of a well-rounded display.

When modifying existing gardens, rely upon the inspiration art and mathematics can provide. Those mechanics will provide a framework for design decisions. The purpose in utilizing time-worn methods is to proDuce a garden that will refresh both the eye and the soul.

Enjoy this journey in artistic and mathematical design.

Mary Warren is the Owner of Gardening Artists located in Seattle, WA. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree from the California College of Arts and Crafts and a Master of Fine Arts Degree in Sculpture from the University of Washington. She has been gardening since she was four years old, when her mother showed her how to plant fragrant sweet peas.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

|

Growing Conifers in Hot and Humid Climates

By Web Editor

November 29, 2019

Follow a Raleighite's adventure in growing his conifer garden.

A dwarf California red fir (Abies magnifica `Nana')

According to conventional wisdom, the only fir which will grow in North Carolina outside of the mountains is Abies firma. Conventional wisdom also suggests that Abies firma is not a particularly attractive tree. About eight years ago, however, as I was trying to establish the most attractive landscape possible, it was clear that I needed to include Abies plants, if possible, and I could not find evidence, anecdotal or otherwise, which would verify these myths.

Therefore, I decided to give it a go and, in 2007, began planting every Abies species I could get a hold of which I thought might have a chance in our hot, humid climate. In 2008, I began finding Abies grafted onto Abies firma and nordmanniana and I bought almost as many as I could find over the years. My interest in growing Abies has also led me to other notable gardens in the area where firs are growing. Thus, I now have gathered quite a bit of anecdotal experience about growing Abies in central North Carolina. The purpose of this article is to share my experience, to open up more discussion and trialing of Abies, and to motivate more growers to graft firs on Abies firma rootstock.

Conifer Growing Challenges in the Southeast

Raleigh certainly does not seem like a great place to grow firs. The soil is the traditional southern red mud: slick when wet, hard as a brick when dry, and drains poorly all the time. The weather is hot and humid, and the summers are long. We typically get long stretches, up to six weeks, during the summer, when the low temperatures do not dip below the low 70’s. It is not rare to have months where the highs stay in the upper 90’s to over 100. Summers usually last for four months with hot temperatures beginning no later than mid-May and lasting through mid-September. This climate is certainly not the cool dry mountain habitat where I think of firs thriving.

Nonetheless, the allure of firs is strong. No other genus offers the same bright green soft foliage with the sparkling silver undersides of the needles. Keteleeria comes close, but can’t rival the beauty of Abies with its perfectly symmetrical form and tiered layers of branches. Then Abies offers so many spectacular cultivars with weeping and pendulous forms and a broad range of green, yellow and blue hues. The cones of many firs are also particularly noteworthy; most have fragrant needles (when crushed); and some even have fantastic bark (e.g. Abies squamata). The desire to grow Abies is probably obvious to any member of the American Conifer Society.

A view of momi firs (Abies firma) in a conifer garden

Preparing for a Conifer Garden in a Hot and Humid Climate

Despite the climate and soil challenges, I remain surprised that there is not more available information about growing firs in the Southeast. There is a strong horticultural tradition in North Carolina with the mountains’ Christmas tree industry and particularly in Raleigh, the home of North Carolina State University. The late NC State horticultural professor, JC Raulston, is credited with originating the idea of grafting firs onto Abies firma rootstock, but it is still extremely difficult to find even first-year grafts available for purchase in Raleigh or elsewhere in the Southeast.

Eight years ago, even with limitless information and sharing of ideas on the Internet, I could find no specific information about the survival of any fir other than Abies firma. Even today, Tom Cox and John Ruter’s recent excellent book, Landscaping with Conifers and Gingko for the Southeast, is the only publication I am aware of which discusses growing this genus with any degree of thoughtfulness.

My story begins in the spring of 2005 when my wife, two small kids and I moved to Raleigh for my work. After moving five times in nine years, we wanted to find our long-term home. We bought a house near downtown Raleigh on just under a half-acre lot which was covered in loblolly pines which had been haphazardly scattered across the backyard. These trees were messy, unattractive (in this setting) and their placement made it hard to throw balls and play games with the kids, and, as a result, we had them removed before we moved in August of 2005.

Starting a Conifer Garden in the Southeast

I immediately went about correcting this insult to Mother Nature by planting trees in more suitable positions in my yard and did as much research as I could to find the best and most beautiful trees possible. The Internet was quite helpful, and I also discovered Michael Dirr’s Manual of Woody Landscape Plants in 2005. I read it cover to cover and searched long and hard to find trees like Emmenopterys henryi, Davidia involucrata, Stewartia monodelpha, and Cornus controversa ‘Variegata.' In 2005, since I had a long timeline, I was willing to start with some small trees, but I wasn’t willing to take much risk on a tree’s survival. For the first several years of my yard, I did not include conifers since I was under the impression they would not do well.

In 2007, my family (now three kids) took a walk through nearby Duke Gardens. I was particularly impressed with a pendulous form of Picea omorika as well as a specimen of Sequoia sempervirens ‘Henderson Blue,' and the “game” in my yard suddenly changed. During the next several years, my “yard” transitioned to a “garden” as I included conifers. Other factors were also coming into play. My plants required quite a bit of water, and we were in the middle of a severe drought. Restrictions on irrigation were instituted in Raleigh, and, as a necessity, I had a well drilled in our yard so that I could irrigate as much as needed (all my woody plants are on drip irrigation).

I also realized that these conifers, with which I had been fascinated, would benefit from better drainage. I began bringing in the first of what would be hundreds of cubic yards of specially mixed topsoil with 30% PermaTill to simulate Rocky Mountain soil the best I could. My wife was really patient with me as we seemed continually to have piles of topsoil in our driveway for a couple of years so that I could make elevated planting beds. The kids loved to climb these alluvial hills, spreading dirt everywhere, including inside the house. Finally, in 2010, my wife and I added a covered porch to the back of our house so that we could enjoy our “garden” (she still calls it our yard). I took the occasion of this renovation project to have stacked stone walls added to border the elevated beds and also to create stone walkways which would wander around the yard. Thus, a reasonably good setting for conifers was created.

The conifer, ‘Glauca Nana’ Min fir (Abies recurvata ‘Glauca Nana’) from China

Sourcing Conifer Seedlings from Warmer Regions

In 2007, I began ordering seedlings of firs from China and the Mediterranean region, since these areas seemed to have heat similar to ours. Most of these species seemed pretty obscure, and I thought it was possible that they had not been grown here before. I did realize that JC Raulston had access to just about every plant in the world, but thought it was possible that he may have gotten distracted from experimenting with Abies. As mentioned above, I could certainly find no record or person who remembered his growing some of these obscure species.

When my first Abies plants arrived, it turned out that some had been grafted (Abies nebrodensis, Abies cilicica) presumably onto Abies balsamea root-stock. I also bought an Abies koreana ‘Horstmanns Silberlocke,' beautifully grown in a three gallon container from a reputable grower, but likely grafted onto Abies balsamea, as well. Each of these “heat tolerant” firs which had been grafted were dead by late June of 2007—consistent with conventional wisdom! I also bought Abies bornmuelleriana, Abies x borisii-regis, Abies cephalonica, Abies homolepis, Abies koreana, Abies numidica, Abies chensiensis, Abies fabri, Abies delavayi, all of which eventually died.

During this period I also bought seedlings of Abies firma, Abies recurvata var. ernestii, Abies pindrow, Abies holophylla, and, a year later, Abies nordmanniana, all of which remain alive and appear to be quite healthy. I did lose an Abies nordmanniana and I also chose to remove a living Abies sachalinensis var. mayriana. It was a beautiful little tree, but it appeared to be struggling while my other seedlings appeared to be thriving. Impatience compelled me to yank it out after it had survived five summers. It also helped that I had one grafted onto Abies firma rootstock.

Success Stories from a Conifer Garden in the Southeast

Over the last 7 years, I have been able to make some observations about these plants. I realize that my experiment with these firs is far from scientific. First of all, I bought only one of most of these firs, and I also had to rely on the seller for their true identity (it’s hard for me to distinguish young specimen of Abies cephalonica from Abies holophylla). The planting conditions also varied in terms of sun exposure, drainage and watering. Thus, my comments on these individual species are anecdotal.

Nonetheless I am particularly impressed by Abies recurvata and Abies holophylla. Both are growing vigorously and have added almost 1' of growth each of the last two years. The Abies recurvata is particularly impressive since it was not planted in particularly special soil, and its root zone has definitely extended into the native North Carolina clay. However, I’m not convinced that either of these plants offers much which visually distinguish it from Abies firma, but it is possible the whiter undersides of the Abies holophylla needles may make it more attractive. I have seen several very attractive older specimens of Abies holophylla at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston. Abies firma grows quite well for me and I find it can be a very attractive tree.

A conifer seedling, Shensi fir (Abies holophylla) growing since spring 2008

I have read observations that it is more “open-growing” than other firs, and that the course needles are unattractive. In Raleigh, we are fortunate to have quite a few mature Abies firma trees planted around town and most have beautifully tiered dark green layered branches. While I also prefer the firs with shorter, softer fragrant needles with white undersides, from a distance, large healthy Abies firma specimen are gorgeous conifers. Abies nordmanniana and Abies bornmuelleriana seem to be borderline here in Raleigh.

There are some large specimens of Abies nordmanniana about 30 miles northeast of Raleigh in Hillsborough NC, and Tony Avent is growing a beautiful specimen (about fifteen years old) of Abies bornmuelleriana at Juniper Level Botanical Gardens at his Plant Delights horticultural nursery about 15 miles southeast of Raleigh. I think these two species are particularly beautiful, but I have not had the greatest success with them. My one living Abies nordmanniana lost its leader last year, but still grew about 5" this year. It looks quite healthy, but I’m not confident that it’s thriving yet.

On the other hand, I am excited about the prospects of Abies pindrow. I bought one of these in the fall of 2007 and thought it was so attractive that I bought another the following spring. The long light-green, soft needles are beautiful, and the branches are pendulous with up-growing tips. They are native to what I’m told is a very wet part of western China. So far, our moisture hasn’t seemed to bother them as both of my seedlings seem to be quite healthy. I have one tree in mostly sun, and another in almost full shade, and both seem to be reasonably full in appearance. There does seem to be a question about the cold hardiness, but mine survived 8°F this past winter, and the specimen at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston is very healthy and has been growing for at least ten years.

Lessons Learned from a Heat-Tolerant Conifer Garden

While I was buying seedlings in 2007, I was also trying to find grafted firs which might survive our heat. Since firs grafted onto Abies firma rootstock were so scarce, I experimented with other rootstock. I bought quite a few on Abies nordmanniana rootstock. Three of my most beautiful firs are grafted onto Abies nordmanniana rootstock. I have four firs which have survived at least six summers in my yard. My Abies magnifica ‘Nana’ is probably the biggest surprise. This western North American fir is not one I would expect to do well here, but is full, colorful and grows at its expected rate of 3"– 4" per year.

My Abies nebrodensis x umbellata ((Abies homolepis x firma) x nebrodensis) certainly should be heat tolerant given its parentage and has not disappointed. It is almost 6' tall, has the most luxuriant soft blunt dark green needles with bright silver undersides and grows 6"– 8" a year. Similarly, my Abies pinsapo ‘Glauca,' which was bought as a 2' 6" B&B plant in spring of 2009 looks great, grew 12" last year, and is now about 5' tall. Unfortunately, I have had more failures than successes on Abies nordmanniana rootstock, even with plants which should be heat tolerant.

I have lost three Abies koreana ‘Horstmanns Silberlocke’, an Abies koreana ‘Aurea', an Abies pinsapo ‘Aurea,' an Abies numidica and an Abies concolor ‘Blue Cloak’ I thought would take our heat. I even bought several firs grafted onto Abies koreana rootstock. This reputable grower suggested that drainage was the key to success and that the Korean fir rootstock was heat tolerant. I planted all of them in perfectly draining soil, but all were dead by mid June of the year I received them. To their defense, however, these plants were all dwarfs which have also proven to be challenging even on Abies firma.

Text and photographs by Harrison Tuttle.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

|

The Importance of Conifer Reference Gardens

By Sue Hamilton

November 15, 2019

Dr. Sue Hamilton talks about how we can preserve and document conifer species with ACS reference gardens.

It is estimated that there are 270,000 plant species in the world, and one in eight are threatened with extinction. According to Botanical Garden Conservation International (BGCI), which has just completed the first comprehensive assessment of the threatened plant species in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, only 39 percent of the nearly 10,000 North American threatened plant species are protected in collections.

In the United States, although in commercial production, Abies fraseri, Tsuga canadensis, and Tsuga caroliniana are all imperiled conifers due to a non-native pest, the woolly adelgid (specifically Adelges tsugae; Adelges piceae). If these conifers are not conserved ex situ, meaning conserved in collections outside of their natural habitat, they may not survive in the wild. Whole stands of hemlock in the Blue Ridge Mountains and of Fraser fir in the Great Smoky Mountains are not just threatened, but already gone. Just as the American chestnut was decimated from existence due to a fungal blight, the same could happen to these conifers.

Conserving Conifers in Reference Gardens

Ex situ collections which are well-documented and genetically diverse can directly support in situ conservation by providing seeds or plants needed to reintroduce extirpated populations. (In situ conservation is maintaining populations of plant species in their native habitat, where they are exposed to and affected by natural, ecological, and evolutionary processes).

ACS Reference Gardens are important ex situ plant collections for conserving conifers in the United States outside of their natural habitat, providing a safety net for species whose survival in the wild is threatened. Initiated in 2007, the ACS created its Conifer Reference Garden Program to develop public conifer collections in a variety of geographical locations throughout the United States.

They play an integral role in the mission of the ACS to develop, conserve, and propagate conifers; to educate the public about these unique plant species; and to make existing conifer collections known. ACS Reference Gardens offer visitors an opportunity to see living conifers in a planted setting illustrating their unique characteristics, diversity, colors, shapes and growth habits in their region of the country.

The University of Tennessee Gardens Conifer Collection Development

Being a university garden, we support the teaching, research, and outreach mission of our university. The UT Gardens in Knoxville were awarded ACS Reference Garden status in 2008. This recognition would never have been possible without the invitation to join and get involved with the ACS from members Maud Henne. The passion and enthusiasm which these two women have for conifers and the ACS is contagious and so, through their encouragement, the UT Gardens joined the ACS in 2005.

We only had 70 conifer specimens in our collection at the time. By the time we helped host the ACS National Conference in 2006, we had increased our collection to 185 conifer specimens. By 2008, our collection had grown to 356 specimens and 17 genera and by 2010, the collection had increased to 401 specimens and 17 genera. This tremendous growth in our conifer collection would not have been possible if it had not been for the ACS Reference Garden Grants.

A 2007 grant provided funds for plant acquisition and anodized aluminum permanent interpretive labels. A 2009 grant was used to support a 2010 conifer symposium conference, in which there were 75 participants, 5 speakers, and a conifer plant sale. In the summer of 2010, the UT Gardens participated in the 8th World Botanic Garden Congress held in Ireland where we presented a poster on the ACS and the important role the ACS Reference Garden program plays in conserving the world’s conifer species.

Conifers in the University of Tennessee Gardens

Three hundred miles west of the UT Gardens in Knoxville are the UT Gardens in Jackson, Tennessee. These Gardens are the campus grounds of UT’s West Tennessee Research & Education Center. Jason Reeves is the distinguished horticulturist over the Gardens and is responsible for them becoming a Conifer Reference Garden in 2009. Since then, Jason has grown the conifer collection from 90 specimens to over 200. A 2011 grant from the ACS SE Region provided for new anodized aluminum permanent interpretive labels for the collection.

The ACS Reference Garden Program Enhances Student Education

The ACS Reference Garden Program at UT Knoxville plays an integral role in the professional education and development of our students. Student interns employed in the UT Gardens and majoring in plant sciences are involved in all aspects of the Gardens’ conifer collection development: accessioning, de-accessioning, database management, planting, labeling, GPS documentation, pruning, and fertilization.

These students receive invaluable education and training in ex situ collection development and management and a unique hands-on opportunity to enhance their understanding of plant conservation. Interns also earn credit towards their degree for their work-study experience with our ACS Reference Garden Program. In addition to interns, numerous students taking plant identification classes in botany, environmental sciences, horticulture, forestry, and ecology are as well exposed to the vast array of conifers in our reference garden collection.

The Long-Term Benefits of a Conifer Reference Garden

More than 200 million people visit botanic gardens every year, and these institutions often provide the only plant focused education programs available to students of any age. Ex situ collections maintained by botanic gardens, if effectively interpreted and incorporated into programming, can play a critical role in providing information about theimportance of plants, the need for their conservation, and the actions people can take to help preserve North America’s plant diversity.

The UT Gardens are one of 18 ACS Reference Gardens in the United States which have been established since 2007, when the program was initiated. Although a young program, it shows great promise in encouraging and ensuring the ex situ collection of conifers in all regions of the United States for conservation, education, and research purposes.

According to BGCI, the following conifer genera and species are threatened and should be conserved in ex situ collections. If you know of any of these threatened conifers to be in a collection somewhere, you can report this information here and help in the world assessment of plants in ex situ situations.

Photographs from The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2014 issue of Conifer Quarterly.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

|

The Endangered Vietnamese Golden Cypress

By Web Editor

February 15, 2020

Learn more about the newest golden cypress that was discovered in Vietnam.

A wide shot of the conifer, Vietnamese golden cypress (Cupressus vietnamensis)

In 2008 Chris Reynolds, Curator of the Bedgebury National Pinetum in Kent, and Dan Luscombe, Assistant Curator, traveled to Vietnam as part of Fauna and Flora International’s Global Trees Campaign, which works to save threatened trees from extinction.*

Bedgebury is the world’s leading conifer collection, managed by the Forestry Commission. The task of Dan and Chris was to offer advice and expertise to the Centre for Plant Conservation (CPC) in Hanoi on measures to conserve five rare and highly endangered conifer species, all of which have been seriously affected by logging, habitat loss, and are likely to be further threatened by climate change.

A New Member of the Conifer Family

Among these endangered trees was the Vietnamese golden cypress, Cupressus vietnamensis (previously known as Xanthocyparis vietnamensis), which in 1999 became the world’s most recently discovered conifer genus. Its predecessor was Australia’s Wollemi pine in 1994. Only three or four new conifer species have been discovered in the last fifty years.

Basing themselves at the Bat Dai Son Nature Reserve in northern Vietnam and accompanied by staff from CPC, Chris and Dan scaled the remote limestone karst mountains to where the few known golden yellow cypresses grow. Fewer than 500 individual trees are known in two small pockets, making it a very high priority for conservation.

Chris Reynolds with mature Vietnamese golden cypress (Cupressus vietnamensis)

A Golden Cypress in Trouble

Field surveys by CPC, supported by the Global Trees Campaign, had established that low reproduction in the wild was one of the problems facing the species; and, attempts by the CPC to produce seedlings in a special tree nursery at Bat Dai Son to supplement the wild population had met with very limited success.

In 2009, Matt Parratt from the Alice Holt Forest Research Centre in Surrey made a follow-up trip to Vietnam to try and establish why the Vietnamese golden cypress was not reproducing from seed. He was available to advise on the optimum time to collect seed from the species and on identifying which cones might potentially provide viable seed.

During the following year, Nguyen Quang Hieu from CPC visited Bedgebury Pinetum with seed from the golden cypress. Using x-ray equipment from Alice Holt, they identified which seeds appeared to contain embryos. These were sown in seed trays in the nursery at Bedgebury in May 2011.

A close-up of a Vietnamese golden cypress (Cupressus vietnamensis) seedling

Sprouting Hope for the Golden Cypress

So far, fourteen seedlings have germinated, for the first time outside Vietnam. In addition, these are the only surviving seedlings in captivity anywhere in the world. In four years time they will hopefully mature enough to be planted out in the Pinetum, joining nine other golden cypresses grown from cuttings donated by the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh and planted in 2005.

They are also the first ever planted outside Vietnam. Despite the much colder British climate, these specimens are doing well. The lessons learned on how to germinate and grow these rare trees from seed will be shared with CPC in Vietnam to enable them to produce seedlings to reinforce populations in Vietnam and support conservation of the species in the wild.

While the successful germination was taking place, CPC staff discovered a new stand of just fourteen golden cypresses in northern Vietnam. Although most of them were dead or badly damaged, one surviving tree stood 20 meters tall (60’), with a diameter of 1.2m, making it the largest specimen yet discovered. Seed from this new population has been collected by the CPC staff, and the Bedgebury team hopes to raise seedlings from it, in order to increase the genetic diversity of this endangered species.

*The Global Trees Campaign, a joint initiative between Fauna and Flora International (FFI) and Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) works to secure the future of the world’s threatened tree species and their benefits for humans and the wider environment. In addition to working to save rare conifers in Vietnam, the Global Trees Campaign and its local partners are also saving baobabs in Madagascar, magnolias in China and other highly threatened trees around the world. See www.globaltrees.org.

Text and photographs by Dan Luscombe and Chris Reynolds.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2012 issue of Conifer Quarterly.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

|

The Origin of Conifer Cultivars

By Robert Fincham

October 17, 2021

Picea abies 'Humilis' at Devizes as described in opening paragraph

Text and Photography Bob Fincham

The Pinetum at Devizes in the UK once belonged to Humphrey Welch, its creator. He wrote an authoritative book on dwarf conifers. In this picture, taken at the pinetum, is a most interesting specimen. Just above the golden Lawson cypress to the left is a Picea abies ‘Humilis’ (Humilis Norway spruce) with three different kinds of foliage: an exceptionally dense ball at the peak of the Lawson, another slightly less dense ball to its left, and, more typically, ‘Humilis’ foliage just above it. These are all growth sports or reversions on the same plant. If cuttings were taken and propagated from each of these sports, new cultivars might be the result.

Picea pungens ‘St. Mary’ (St. Mary Colorado spruce) is a most attractive, low-mounding form of Colorado spruce that originated as a witch’s broom. Pinus strobus ‘Horsford’ (Horsford eastern white pine) is a dense bun discovered as a seedling growing in Vermont. At the same time, Pinus strobus ‘Sea Urchin’ (Sea Urchin eastern white pine) is a dense, bluish bun grown from a witch’s broom seedling. Picea glauca ‘Blue Teardrop’ (Blue Teardrop white spruce) developed as a fast-growing branch on Picea glauca ‘Echiniformis’ (Echiniformis white spruce).

Obviously, all known cultivars had to originate in some manner. The ones listed in this article are a few examples used to explain the various origins of these plants. All the plants are cultivars.

Cultivars are selected variants of the typical species with garden merit. They can be propagated asexually to produce duplicates of themselves. A cultivar cannot be grown from seed and can be traced back to a single mother plant. The name is written inside single quotes, and Latin forms have not been recognized since 1958.

Several plants are incorrectly named cultivars. Let me mention two groups. The first group would be most plants that are called simply ‘Pendula’. For example, the very first Picea abies ‘Pendula’ (weeping Norway spruce) may exist somewhere, but no one can be certain. Since seedlings are commonly produced from weeping forms of Picea abies, they have been propagated, grown, and sold under this name. The same is also true for Pinus strobus ‘Pendula’ (weeping eastern white pine). It comes true from seed as well, and the “mother cultivar” cannot be proven to exist. They need to be given a designation of forma pendula (f. pendula) since that is how they grow. Picea abies f. pendula (pendulous form Norway spruce) and Pinus strobus f. pendula (pendulous form eastern white pine) would be their correct names.

The second group would be plants that are artificially induced to grow in the desired manner by propagating selected material. They are considered cultivariants, a term coined by Humphrey Welch. An excellent example of a cultivariant is Abies procera ‘Glauca Prostrata’ (blue prostrate Noble fir), described as a flat-growing plant that invariably produces an upright leader and eventually becomes a large, conical tree. The grafting of a side branch of Abies (spruce) will generally make a cultivariant exhibiting this kind of behavior.

Closeup view of Picea abies 'Humilis'

The mechanisms that produce cultivars are not very well understood. Still, there are some excellent observations and exciting theories about the various processes at work. Cultivars tend to remain stable, and propagations grow like the parent plant. However, reversions back to species normal do sometimes occur and serve to confuse the issue. I described Picea glauca ‘Blue Teardrop’ (Blue Teardrop white spruce) as originating from a fast-growing branch on Picea glauca ‘Echiniformis’ (Echiniformis white spruce), itself a slow-growing cultivar. This type of activity is quite common in many species. Mutations occur in nature and are often induced by the background radiation present all around us.

When cell divisions are taking place in growing tissues, they are most susceptible to this radiation damage. If such damage occurs at the right time and place, a mutation may result. Since a typical plant of Picea glauca ‘Echiniformis’ has many growing tips, it is not very surprising that such mutations occur quite often in this cultivar. In plants with a more open growth habit (fewer growing tips), such sporting is more uncommon but does occur. Sometimes the sporting affects the color of a plant instead of its shape or growth rate.

Pinus strobus ‘Horsford’ (Horsford eastern white pine) and Pinus strobus ‘Sea Urchin’ (Sea Urchin eastern white pine) both originated from seed. ‘Horsford’ was found growing in the wilds of Vermont by William Horsford. In contrast, ‘Sea Urchin’ was grown in a controlled experiment by Sidney Waxman at the University of Connecticut. Both plants are obviously the products of mutations, but just when the mutation of each occurred is not obvious. ‘Horsford’ may have resulted from a mutation during the sexual activity that created the seed, from which it germinated. However, the change may have occurred at an earlier time, as evidenced by Waxman’s work.

For over twenty years, Waxman collected seed cones from congested masses of growth, called witch’s brooms, and grew seedlings from them. These seedlings had a high percentage of compact and dwarf forms among them. Several exhibited enough merit and individuality to warrant cultivar designation and naming.

Witch’s broom seedlings indicate genetic aberrations since such a high percentage of dwarfs is produced. That percentage could easily be much higher, except that almost 100% of witch’s brooms have only female flowers. The fertilizing pollen must come from male flowers on standard parts of the tree. Other dwarf plants from seed collected in the wild and grown commercially at seedling nurseries and those found in the wild like ‘Horsford’ may often be produced from an unnoticed witch’s broom in the region of the seed’s origin. If not, the seed was created by a genetically damaged sperm, egg cell, or zygote.

Picea abies 'Gold Drift' at Coenosium Gardens when the author lived near Eatonville, WA

Cultivars originating from seed tend to behave stably and are relatively dependable. Those produced from cuttings taken from a witch’s broom are often another story altogether. Take, for example, one plant not yet mentioned, Pinus sylvestris ‘Riverside Gem’ (Riverside Gem Scots pine). This progeny of a witch’s broom develops into a dense, upright plant with a pleasingly conical habit. Interestingly, ‘Riverside Gem’ plants will consistently die after about twenty years, a trait observed in several cultivars propagated from witch’s brooms (with varying life spans). The ‘Riverside Gem’ witch’s broom was shaped like a broad cushion and appeared dense enough for a person to sleep upon. Plants propagated from this broom appear entirely different. They are thick, narrowly conical trees that reach about eight feet and die when they reach twenty years.

The cultivar, Picea pungens ‘St. Mary’, is a much better-behaved plant than ‘Riverside Gem’. It maintains the dense, low habit of its originating broom and is a most desirable plant. It develops into a full cushion about three feet across and 18 inches high, when it is twenty years old.

Several theories attempt to explain the origin of witch’s brooms. Most brooms are thought to be viral in origin. A virus upsets the hormonal balance in an elongating bud, causing it to grow little but produce many lateral branches. Such growth continues until the broom chokes itself or is shaded to death, provided that the hormonal irregularities themselves are not fatal. If this type of broom is propagated, the progeny will fail immediately or within just a few years. One clue that a discovered broom is of this type would be observing several brooms within a small area, indicating that the virus spread through the site like a disease.

Brooms that do propagate successfully are attributed to other causes. These “other causes” have never really been defined. But some interesting facts or clues are known. Cytokinins are found at a higher-than-normal level in witch’s brooms. Cytokinins are hormones that do not move very freely around the plant. Their presence stimulates cell divisions. Another hormone named gibberellin is present at reduced levels. It encourages shoot elongation. This sort of combination would tend to promote the formation of many shoots while keeping them short.

Picea glauca 'Blue Teardrop' at Coenosium Gardens, Eatonville, WA

These unknown agents upset the hormonal balances in a bud. How they can persist into the resulting brooms is a question that still needs explanation. Since these agents apparently have a genetic relationship to the broom, the problems are even more complicated than they at first appear. Grafting a small piece of a “non-viral” witch’s broom onto a seedling will generally create a plant with the original broom’s characteristics. The hormonal imbalance apparently remains, even though a new stem and root system with a standard balance have been added. Of course, the broom itself was on a species-normal trunk and root system while attached to the parent tree. Either a causative agent was in the piece of the broom that was grafted, or the genetic structure of its cells was imprinted with a new hormonal code equal to that of the whole broom.

Almost all witch’s brooms that have been observed to flower have been female. Pinus sylvestris ‘Longmore’ (Longmore Scots pine) is a male broom. If the egg cells are fertilized in the strobili of a broom, the resulting seeds produce a high percentage of dwarf plants. Those dwarfs result from the normal sperm cell from the tree's male flowers fertilizing the genetically dwarf eggs (zygotes) of the abnormal witch’s broom. Either the eggs have an altered genetic structure, or the causative agent is somehow encapsulated within the seed. The variation of growth rates exhibited by the seedlings, however, indicates genetic changes. A causative agent would be expected to produce a relatively uniform population of typical species and witch’s broom duplicates, with little or nothing in between.

Some seedlings from witch’s brooms will die at a young age, develop into weak, sickly plants, or consistently exhibit dead areas. Other seedlings from the same source will be standard in all observable ways. Still others will develop into compact or dense plants, and a few will become very dwarf. Such variation within a population is thought to be due to genetic factors.

Picea pungens with the original broom named 'J.B.'s Broom' in the center of the tree, Bickelhaupt

Arboretum, IA Photo by Dennis Hermsen

Many cultivars originate as abnormal seedlings from apparently normal parent plants or as branch mutations on otherwise typical trees. For example, Pinus strobus ‘Fastigiata’ (fastigiate eastern white pine) gets exceptionally large, and the branches widen as it ages. In Vermont, a fastigiate Pinus strobus was found that maintains its spire-like growth habit. Heavy winter and spring snows have had little effect upon its shape. Several similar plants are growing together, but the specimen with the best growth habit was selected and named Pinus strobus ‘Stowe Pillar’ (Stowe Pillar eastern white pine).

Any seedling population will show variations in growth habit, rate of growth, and coloration. This variation is normal but seldom produces anything that varies very much from the species norm.

Color mutations can occur in seedlings or on the branch of an otherwise average tree, such as a yellow branch mutation I found on Picea abies ‘Reflexa’ (reflexed Norway spruce). This branch was the sport that produced a cultivar named Picea abies ‘Gold Drift’ (Gold Drift Norway spruce).

Pinus strobus ‘Hillside Winter Gold’ (Hillside Winter Gold eastern white pine) was discovered growing on a slope next to an interstate highway by Layne Ziegenfuss. There was a large group of yellow trees in the area. They were unnoticeable in the summer because they were green at that time of the year. He selected the one with the best color for propagation. He almost threw the grafts away when they turned green in the propagation house. The trees on the slope were gone the following year. Someone had removed the original grove. Layne searched for the seed source, expecting to find a yellow branch somewhere, but never located a seed source. Many similar variants have been found in other species since Layne’s discovery.

Genetics appear to be a crucial factor affecting the origins of new cultivars. The agents affecting the needed changes in a typical tree's genetics to produce aberrant growth or seed are not entirely understood. However, Nature works to create these mutations, and the process has produced a treasure trove of attractive plants for the modern homeowner.

A closeup picture of 'J.B.'s Broom'

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

|

How to Care for Your Growing Conifer and Evergreen Garden

By Bill Blevins

April 19, 2020

Discover the lessons learned from a conifer collector about keeping a garden of evergreens.

The conifer, Picea abies f. pendula (pendulous form of Norway spruce)

I planted a Metasequoia glyptostroboides (dawn redwood) seedling in my Rochester, NY, backyard in 2007. My garden sported, at the time, dozens of other, newly-planted perennials, annuals, vegetables, and trees, but the dawn redwood made an impression on me.

It grew fast and was uniformly shaped like a pyramid, with no help from pruning. I learned that it was one of only a few deciduous conifers. Dawn redwoods have an interesting history, too, and, as a result, I thought it was just perfect. That plant became my tree, and I became a conifer collector.

A Conehead's Journey!

A few years later, my wife, Tracy, and I moved to Spotsylvania, VA. We bought a house on a two-acre lot in a new subdivision. The building contractor had planted an ornamental plum tree in front of the house, along with three azaleas, four nandinas, and a holly as foundation plantings in a row below the front porch.

The front yard was in full sun, with hard-packed, fill dirt that had been bulldozed smooth, and covered with a layer of straw and grass seed. Tracy started her new shade garden in the backyard, filling the edge of the woods with her favorite plants, such as hostas, pulmonarias, hydrangeas, viburnum, and many uncommon native trees.

Whenever we went plant shopping, I kept my eye open for unusual conifers. One day I said: “Since you’re gardening in the back, I’ll handle the front.” She agreed.

Learning from a Conifer Collection

I began planting conifers in 2013 – a lot of them. Since then, I have planted hundreds of other trees and plants in my part of the yard. Today, I would guess that our garden contains about 1,800 taxa.

Here are some things I have learned as a new plant collector:

- If you don’t have irrigation, locate plants that need a lot of water close to the house.

- The height, width, and spacing sizes printed on plant labels are an approximation. (Here is a tip: Attend your regional American Conifer Society meeting for the conifer tours. Also, the ACS Conifer Reference Gardens are a good way to see how big conifers mightultimately get in your yard.)

- Many botanical names and most family name printed on plant labels are either misspelled, or just wrong.

- Home improvement big-box stores display and sell lots of plants that are not hardy in the zone where the store is located.

- Once Japanese beetles find a plant they like, that plant is doomed to look bad 10 months of the year.

- Roses are best planted in the yard of someone else.

- Daylilies do not ever look good as a border plant.

- Make drainage a top priority when planting conifers.

- Educate yourself about rootstocks suitable for your zone before you buy grafted conifers.

- Thoroughly check and try to fix the roots on every conifer that you plant.

I could probably list another dozen things that I’ve learned and that I could write a book about for each point above, but, after the heat and lack of rain at my house this summer, I’ve got to make some changes.

The conifers, Acer palmatum ‘Orangeola’ (Orangeola lace-leaf Japanese maple) and Picea glauca var. albertiana ‘Gold Tip’ (gold-tipped Alberta spruce) in the front yard of Bill and Tracy Blevins' garden in Spotsylvania, PA

Watering Conifer and Evergreen Trees

I spend 75% of the time in my garden holding a hose. Due to the soil type and the layout of the beds, an irrigation system is not an option. It takes at least six hours to water my part of the yard with a hose.

This year, I’ve had to water my plants at least once a week. I water some areas in my garden two or three times per week.

Here is a shortlist of things I’ve learned while watering:

- Watering every other day lets me see every plant frequently. I’m not expert enough yet to be able to solve the problems I find, but I can spot them early. I’ve mastered finding sawfly eggs and I was successful at getting ahead of them this year before they ate my conifers.

- Another good thing about spending so much time with each plant is that I can make minor pruning cuts regularly, rather than being surprised and needing to make a major cut.

- That’s about it for the benefits. Navigating three carts with a couple hundred feet of hoses through trees and around beds, while constantly disconnecting and reconnecting them, is a real pain.

- Newly planted conifers initially require more water and, as a result, I’ve started planting annuals near them to remind me to keep them watered.

- Once established, conifers do not require a lot of water.

Spacing Out Conifers and Evergreens

I mentioned that I initially followed the suggested spacing that is printed on my plant labels. I quickly learned that those are normally wrong for my yard. Consequently, I started to spread out my conifers when planting, which led to another problem.

I suddenly had more space between my conifers to plant something else and, so, I did. Those unusual and interesting filler plants are what I’m constantly watering, and they also require the most hands-on maintenance!

I’ve figured out that it is not conifers that require work. It’s all of the other plants!

Planting Between Conifer and Evergreen Trees

After six years, I’ve started relocating plants to make being out in the yard more enjoyable. Conifers are being spaced out appropriate to their real, eventual, and mature size. I’m starting to accumulate pollinator plants in one place.

Milkweed for the Monarch butterflies grows where I can easily mow around the bed. Lower-maintenance, ornamental grasses and bulbs are filling in the new, empty spaces between the conifers.

Hopefully, after another five years, I’ll be spending a couple of hours every other day enjoying my plants, while holding a glass of wine, rather than the end of a hose.

Or, maybe it will just rain.

Favorite Conifers

Conifers I Can’t Grow

Plants I will Never Grow Again

- Passiflora incarnata (purple passionflower)

Fun, But Not Conifers

- Aralia spinosa (devil’s walking stick)

- Aralia cordata ‘Sun King’ (Sun King Japanese spikenard)

- Tulipa sylvestris (wild tulip)

- Athyrium felix-femina ‘Godzilla’ (Godzilla lady fern)

- Oenothera glazioviana ‘Tina James’ (Tina James red-sepal evening primrose)

Photographs by Bill Blevins.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

|

Quarry Lakes Regional Recreation Area: A conifer collection hiding in plain sight

By Leah Alcyon

December 19, 2020

San Francisco Bay Area's Quarry Lakes Park has a wonderful conifer collection

Fun place to visit in the San Francisco Bay Area

Last month we witnessed a perfect example of how the American Conifer Society brings people and conifers together: Sara Malone (website editor) meets Todd Soderberg (Conehead) and Todd introduces Sara to David Pellarin, retired head gardener at Quarry Lakes Regional Recreation Area in Fremont, CA.

In the late 1990’s, David was the first employee of this former-quarry-turned-into-a-park. In the almost two decades since, as the gardener, has helped to transform a defunct gravel pit into an up-and-coming arboretum with over 101 species of conifers.

Fremont is on the southeast end of San Francisco Bay, and is bordered by Alameda Creek, which is the source of the water for the lakes that were formed from the gravel pits. In a stunning terraforming of the landscape, the lakes now resemble a bucolic scene painted in the Impressionist style, with trees reflected in the water, and people swimming, fishing and boating. To the east of the 471-acre park is a line of mature trees, remnants of the California Nursery Company, which was established in 1865 and created both a backdrop and a source of plant material for the new park.

History of Quarry Lakes Regional Recreation Area

David, now retired but continuing to work as a volunteer, led a small group of us on a ‘tour of the trees’ on a hazy, warm November day, all the while providing historical detail about the Park’s founding and development. After the quarry operation was closed in 1976, the Alameda County Water District and East Bay Regional Park District purchased the property and started restoration. One of the first steps was the removal of “feral” vegetation, no small feat. As David explained the challenges of planting trees in gravel, nursing them through the extended drought of 2011 to 2017, we were amazed to see how vibrant the growth was in all but a small number of specimens. The list of conifers and a map of their locations in the park illustrates the commitment to both California natives and unusual species that will thrive in an environment that gets hot in the summer but is frost-free in the winter. Drip irrigation is provided to trees not situated in lawn areas and a fence was installed to protect young plants from the ravages of the local deer population.

Our walking tour on the Old Creek Trail included the Bald Cypress Grove and the Rare Fruit Tree Grove on the Isla Tres Rancheros. Although Covid-19 restrictions have changed some park usages, there were many people masked and socially distanced enjoying the park. Trees are each labeled with a post, which contains an alpha-numeric code and the corresponding genus and species names. You can use the code to cross-reference with the map that is linked above.

Quarry Lakes highlights

Taxodium distichum x mucronatum 'Nanjing Beauty' (T9)

‘Nanjing Beauty’ is a conical, deciduous to semi-evergreen conifer with needle-like leaves. It is a hybrid cross of Taxodium distichum (bald cypress) and Taxodium mucronatum (Montezuma cypress). This cross was made in China in the late 1970s / early 1980s by Dr. Chen Yong Hui of the Nanjing Botanical Garden. Nanjing Beauty is noted for its rapid growth rate, ease of rooting, high alkalinity resistance, good fall foliage retention and absence of knees.

Widdringtonia cedarbergensis (W1), entire tree (l), close up (r)

Cape, or Clanwilliam, cedar grows to about 15 to 22 feet tall but in protected places up to 65 feet. Old trees are spreading, gnarled and massive, with reddish gray, thin, fibrous, flaking bark. Juvenile leaves are up to 0.75 inch long and and 1 inch wide; adult leaves are up to 1.5 inches long.

Cupressus sempervirens, with uncharacteristic horizontal lateral branches

This Cupressus sempervirens, (C21, erroneously listed as “Hoizontalis”), looks more like a Cupressus nootkantensis ‘Green Arrow’ than what most of us think of as Italian or Mediterranean cypress, the common names of C. sempervirens. The vast majority of the C. sempervirens in cultivation are cultivars with a fastigiate shape, with erect branches forming a narrow to very narrow crown often less than a tenth as wide as the tree is tall. Formerly, the species was sometimes separated into two varieties, the wild C. sempervirens var. sempervirens (syn. var. horizontalis), and the fastigiate C. s. var. pyramidalis (syn. var. fastigiata, var. stricta), but the latter is now only distinguished as a Cultivar Group, with no botanical significance. (Wikipedia)

C. sempervirens seed cones

David Pellarin stands next to a Taxodium ascendens

Taxodium ascendens (T2) is in the park area called Bald Cypress Grove and although it is dry in November, as soon as the rains come and the lakes fill, this area will be flooded. T. ascendens is commonly known as pond cypress, and is distinguished by its upwardly pointing needles.

Taxodium ascendens branch, showing fall color and female cones

Cupressus abramsiana, also known as Hesperocyparis abramsiana