|

|

Posted By Administration,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Web Editor

July 1, 2021

What is a Conifer Tree?

What most people think when they hear 'conifer'

So what is a conifer tree, anyway? While this seems like a simple question, it has a complicated answer. Most of us have a vague idea; it’s like, a pine tree, right? Well, pines are conifers, but why? And what else is a conifer and is it always a tree? Always evergreen? Always green?

- Conifers are, most simply, plants that have cones. So yes, pine trees are conifers; we all know about pine cones!

Cones on Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) photo by Janice LeCocq

However, some conifers, such a yews, have fleshy cone that look more like fruit.

Other conifers, such as cypress and junipers, have cones with fused scales that look more like berries than what we think of as cones. What all of these bodies have in common is that the actual seeds are ‘naked’ and not enclosed within fruits, as in the flowering plants.

- Are all conifers pine trees? No, there are spruce and fir and cypress and redwoods and dozens more. However, the pine family is the largest family within conifers, and both spruces and firs are members of the pine family (Pinaceae) so for most of us, many of the conifers with which we are most familiar, are pines!

- Are all conifers trees? We all know that classic, Christmas tree shape, and unfortunately conifers get tagged as boring because there is an idea that all conifers look like that. Did you know that conifers naturally occur in 10 completely different shapes, from tall and upright to weeping to flat and spreading? Conifer shapes

- All conifers are not evergreen! Ever heard of a bald cypress, the denizens of the Southern bayous? They got the nickname ‘bald’ because they lose their needles in the winter. So do larch and dawn redwood, but they are still conifers, because they bear cones.

- Not only are all conifers not evergreen, they are not all green! Colorado blue spruce is vividly blue, many other conifers are vibrant yellow or gold, and you can find colors ranging from silver and white through yellows and blues to purple, brown and reddish at different times of the year. Oh, and of course, green!

Gold, green and blue and they are all conifers! Photo by Janice LeCocq

- So ok, we get it now, conifers are complicated, but they all have cones and we know that they all have needles instead of leaves, right? Well…sorry to make it even MORE complicated, but there are a few conifers that don’t have needles, they have leaves! Native to Australia, they don’t look anything like our idea of conifers. So what makes them conifers then? Remember the first bullet point: they bear cones!

Conifers, far from being boring, are one of the most exciting group of plants in the kingdom. While there are only around 800 conifers that occur in nature (as compared to perhaps 28,000 orchids), due to chance mutations and plant breeding, there are thousands of cultivars (short for ‘cultivated variety’) that are wonderful focal points and accents to the garden and landscape.

Conifers add color to the garden all year long! Photo by Janice LeCocq

So add color, year-round interest, texture and structure to your garden by planting some dwarf conifers! join the American Conifer Society to learn more and to connect to a nationwide group of plant lovers!

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Reimagining Your Conifer Landscape Design

By Kenneth Hundrieser

March 7, 2020

Learn how to transform your landscape design and create a conifer garden of your dreams.

The conifer, Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens ‘Globosa’) complemented by

variegated silver grass (Miscanthus sinensis ‘Variegatus’) and

creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis ‘Wiltonii’)

I was given the authority by the condo board to reimagine the front and back yard gardens in 2006, four years after we purchased the condo from my brother. The building is six-flats, with three units on each side, facing south.

The front yard consists of a 50 by 23 plot of land (1,150 square feet), trisected by a curved sidewalk. For most of its existence, the yard was covered by grass with a strip of yews across the front foundation. In the semicircle bed in the middle, various unit owners had planted a few bulbs and numerous daylilies.

The conifer, ‘Pumila Nigra’ Norway spruce (Picea abies ‘Pumila Nigra’) nestled between

Golden Nugget Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii ‘Monlers’), and

Plantain Lily (Hosta ‘Dancing Queen’)

An Overview of the Original Conifer Garden

The center bed was beautiful during the summer when the pastel yellow and peach daylilies blossomed, but that was it. The few bulbs were dwarf irises and tulips. The yews were so badly managed over the years that they looked awful when I moved in. The backyard is slightly larger at 1,500 square feet.

After getting permission to reimagine the plot, I proceeded to draw up plans for the southeast segment of the yard, which included conifers, flowering shrubs and natural hardscaping. One of my specialties, wherever I move, is to add hardscaping using rocks to create gardens.

I typically hunt and find rocks from nearby forests and lakes, creating gardens with rich habitat full of niches for both flora and fauna. I immediately planted my first design, leaving about half of the plot grass and the rest filled with a beautiful variety of trees, shrubs, and perennials.

A Korean fir (Abies koreana ‘Horstmann’s Silberlocke’), Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens ‘Globosa’),

and an unidentified conifer at the sidewalk

This garden began with Pinus cembra 'Blue Mound', Picea abies 'Layne's Globe’, Pinus mugo 'Slowmound', Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Kosteri', Chamaecyparis pisifera 'Golden Mop', Pinus mugo 'Mops', Chaenomeles japonica ‘Cameo’, Syringa pubescens subsp. patula, Corylus avellana ‘Contorta', Robinia pseudoacacia 'Lace Lady', Cotinus coggygria 'Velvet Cloak', Rhododendron 'Thunder', Berberis thunbergii 'Intermedia', and an additional Japanese white pine, which has since succumbed to the drainage from a portable air conditioner unit above.

As beautiful as this plot turned out to be and as happy as I was that the unit owners gave me their seal of approval, I was left hungry to envision and plant more gardens.

Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens ‘Globosa’) in concert with variegated silver grass

(Miscanthus sinensis ‘Variegatus’), ‘Densa’ inkberry (Ilex glabra ‘Densa’), and the unknown conifer on the corner

Experimenting with Conifers

I had always been interested in conifers for their year-round interest, even drawing them when I was a young adult experimenting with various art forms. The first landscaping season at the condo left me with a greater interest in conifers. I spent a lot of time at our local Gethsemane Garden Center searching out the most beautiful conifers I could find that would grow slowly.

They had a wide selection available, so picking out more for the next plot was easy. I turned to the plot under my front windows - the southwestern plot - and designed a garden there for planting the next spring.

When the weather warmed enough, I planted conifers in four focal points for interest to the new plot, including Pinus parviflora ‘Fukai’, Picea pungens ‘Globosa’, Abies koreana ‘Horstmann’s Silberlocke’, with numerous smaller conifers, shrubs, hostas, and grasses, including Miscanthus sinensis ‘Strictus’, Picea abies ‘Pumila Nigra’, Pinus mugo ‘Winchester Compacta’, and Berberis thunbergii 'Monlers’.

The garden beds expanded over time with Japanese maples and many more dwarf and miniature conifers. After many years of growth, I decided there was no longer any place for grass in my life.

A profusion of conifer colors

Moving Away from Monoculture

I teach Environmental Biology at Roosevelt University, and know about the dangers of monocultures. That was a great excuse for getting rid of the grass in the front yard, which I proceeded to do in all three beds, as the gardens expanded.

At this stage, the southwestern plot is completely landscaped, the south center plot just took on its next look with a lot of miniature and dwarf conifers and no grass, and the original southeastern bed will lose the remaining grass skirt during the next growing season.

Our yard now contains approximately 60 conifers, 3 ginkgos, and 5 Japanese maples. The backyard is now fair game for my imagination, and I am working on it, plot by plot.

Part 1 of the dwarf/miniature conifer bed-making

Introducing Dwarf Conifers

This past summer I experimented with adding more dwarf and miniature conifers into a newly de-grassed 60 square foot plot, and I decided to try using leftover chunks of sidewalk debris to build elevation.

Included is a series of pictures highlighting the creation of that garden segment, from laying out the spiral walls of the mound to planting conifers, ferns, dwarf hostas and thymes, to the final mulching stage.

The conifers in this newest plot include Platycladus orientalis 'Morgan' (the featured conifer at the top of the mound), Juniperus horizontalis 'Blue Pygmy', Thuja occidentalis 'Golden Tuffet', Chamaecyparis pisifera 'White Pygmy', Tsuga canadensis 'Jervis', Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Butterball', Picea abies 'Tompa', and Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Bassett'. I cannot wait to see how the newest bed survives the winter, and how the specimens grow together.

Part 2 of the dwarf/miniature conifer bed-making

I have many favorites in this collection, but the one that I check on every single day, is Abies koreana 'Cis'. I absolutely love the Korean firs, but this particular cultivar is my pal.

You know you are doing a good job when passersby, dog walkers and other neighborhood residents and business owners stop and exclaim how beautiful your garden is and how it seems so natural, with the merging of one specimen to the next.

The real reward is watching your garden grow, year after year, and to see how each specimen adapts to its environment and adds its own unique imprint to the design.

The conifer, ‘Cis’ Korean fir (Abies koreana ‘Cis’)

Photographs by Dr. Kenneth Hundrieser.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Conifers of Southern United States

By Web Editor

December 6, 2019

Discover the rich diversity of conifers in South Carolina.

The conifer, Pinus palustris (longleaf pine)

When one conjures up images of the deep South, they typically think of azaleas, magnolias, live oaks, and yes, that noxious vine from China, kudzu. Aside from the ubiquitous pines, scant attention is afforded conifers. After all, when one thinks of conifers, the vast forests of spruce and fir that dominate boreal regions often come to mind.

Although conifers are found in a variety of climates throughout the world, people with a passion for growing conifers and widespread landscape use of conifers is still largely a northern and Pacific Northwest phenomenon. In what is now the southern United States, an immense coniferous forest dominated by longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) once covered more than 90 million acres from Virginia to Texas. This and several other southern pines are still mainstays of the forest products industry.

The conifer, Araucaria angustifolia (Paraná pine)

Native Pines in the South's Best Small Town

I live and garden in Aiken, South Carolina, which sits squarely in this pine forest region. Today, the 11 pine species native to the southern United States are all represented in Aiken. Other native conifers including Taxodium, Juniperus, and Chamaecyparis are also found here. Soils, climate, and cultural history combine in Aiken to provide a rich horticultural history. Today, there are few communities that can match Aiken’s diversity of trees and other plants.

The International Oak Society has credited Aiken with having the most comprehensive collection of oaks in the United States, but Aiken likewise has a wealth of cultivated conifers. Many genera and species not hardy in colder regions, and/or generally uncommon in cultivation, are represented. Last year, when past ACS president Tom Cox visited me, I could sense that he was surprised at the species diversity found within such a concentrated area.

The conifer, Afrocarpus falcatus (Outeniqua yellow-wood)

Conifers at the Hitchcock Woods Preserve

The city of Aiken was laid out in the 1830s by the railroad being built to provide a link from Hamburg (across the Savannah River from Augusta, Georgia) to Charleston, South Carolina. At the time of completion, the railroad was the longest in the world. In the antebellum period, Aiken was a popular summer retreat for coastal planters. In the late 19th century, it became a popular health resort and, later, a winter home for wealthy northerners who pursued hunting and equestrian sports.

It now is a small, vibrant city, retaining an equestrian focus and attracting a growing population of retirees. Today in Aiken’s 2,000-acre Hitchcock Woods Preserve, one can see ancient longleaf pines and other native conifers, including disjunct occurrences of Juniperus communis and Pinus virginiana. In the beautiful Hopelands Gardens, enormous deodar cedars (Cedrus deodara), pines, and rare conifers such as Fokienia hodginsii and Cupressus funebris can be seen. Throughout Aiken’s historic district, broad tree-filled parkways display a remarkably varied tree collection that includes many noteworthy conifers. Quite a few private estates and home landscapes have notable conifers.

The conifer, Wollemia nobilis (Wollemi pine)

Woodlanders in the South

One private estate has an especially varied collection with many rare species from around the world; included are many Southern Hemisphere rarities such as Araucaria angustifolia, A. araucana, Afrocarpus falcatus, Podocarpus parlatorei, and Wollemia nobilis. Everything within a 4-mile radius of downtown Aiken is included within the Aiken Citywide Arboretum project area.

Efforts to locate, identify, and GPS a typical, outstanding, or sole example of every tree species within the project area is underway. The conifers have been largely completed, enabling one to pinpoint an example of many species. While various horticultural varieties of conifers are included, there has not been any special effort to pursue the endless variety of named selections and mutant forms popular with conifer collectors.

Aiken’s collection, therefore, is species focused. We are proud of our tree program and pleased to have this opportunity to introduce a diverse collection of conifers growing in a region of the United States where most visitors may not expect to find them.

Text by Bob McCartney.

Bob McCartney and George Mitchell operate Woodlanders, Inc., an internationally known source for more than 1,000 kinds of rare and hard-to-find plants, located in Aiken, South Carolina.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By administration,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Sara Malone

March 24, 2021

10 Types of Cypress Trees that Everyone Should Know

The graceful weeping branchlets of Kashmir cypress (Cupressus cashmeriana)

Cypress: What's in a Name?

Unfortunately, it is common for people to indiscriminately refer to many kinds of conifers as cypress, even if they are not of the genus Cupressus, and are thus not really cypresses. Since we are supposed to know what we are talking about when we talk about conifers, we will restrict this discussion to those trees which are members of the genus Cupressus, and ignore the others, such as Taxodium (called swamp or bald cypress) or Glyptostrobus (Chinese swamp cypress) and the like. There are enough true cypresses to excite and entice any tree lover.

So now we're on firm footing, right? We're going to look at a short list of conifers that all agree are classified as cypress. Not so fast! This genus, more than any other within the world of conifers, has had its members named, re-named, re-named again, and then, in some cases, sent back taxonomically to where they began. At the time of this writing, there is still disagreement about how some members of Cupressaceae, the family to which all of the genera belong, should be classified. The ACS, perhaps believing that it is preferable not to complicate things unnecessarily, does not recognize the genus Xanthocyparis, the genus Hesperocyparis, or the genus Callitropsis, holding them both to be Cupressus. Should you see plants labeled with those names, worry not. The trees will continue to behave as they do, regardless of what we call them.

Close up of foliage of Cupressus arizonica var. glabra 'Blue Ice'

Cypress can be very long-lived trees, with some reported to be over 1,000 years old. There are cypress native to the Mediterranean region, Asia and North America, and their forms and color vary from narrow upright to spreading to weeping. Cypress are not as hardy as many other conifers native to the Northern hemisphere, with the hardiest, Nootka cypress, able to survive in USDA Zone 5, with average minimum winter temperatures of -10 to -20 degrees F (-23 to -29ºC). For those of you who will indulge in zone-pushing no matter what we tell you, there are reports of some other Cupressus, such as C. sempervirens (Italian cypress) and Cupressus arizonica var. glabra (smooth Arizona cypress) weathering the winters in Zone 6, but most of the trees discussed here are hardy only to Zone 7.

Cypress foliage can resemble that of junipers, which is understandable as they are both members of the cypress family, Cupressaceae. Their cones, too are similar. Some of the most difficult field IDs can be trying to determine whether the specimen at hand is a cypress or a juniper. While both cypress and juniper are associated with dry, hot climates - think the rows of Italian cypress in southern Italy or the Arizona cypress in the American Southwest - there are cypress that are far more verdant. So which cypress should you consider for planting in your garden?

Cupressus nootkatensis 'Green Arrow' (Green Arrow Nootka cypress) in a garden in Northern California

Nootka cypress, also known as yellow cypress and Alaskan cypress, is native to the west coast of North America, from Alaska to Northern California. As one of its common names implies, it is a denizen of cold places and is fully hardy to USDA Zone 5. However, it also grows quite happily in Zone 9, and Tom Cox and John Ruter, in their definitive book on conifers suitable for the American Southeast, pronounce Nootka cypress to be quite adaptable to that climate. While there are any number of Nootka cultivars, 'Green Arrow' is a favorite for garden culture due to its narrow form and rich, deep green color. Its relatively small footprint for a tall tree - it is not uncommon to find them over 20 feet (6 m) tall - makes it one that even a small garden can accommodate. Those 20-footers generally are only about 2 to 3 feet (60 - 90 cm) wide.

A variegated form of Nootka cypress, 'Sparkling Arrow'

If rather than a rich green, you are seeking a little more pizzazz, try Cupressus nootkatensis 'Sparkling Arrow', which is a variegated form of 'Green Arrow'. As with almost all variegated plants, 'Sparkling Arrow' doesn't grow quite as fast as its all-green (and more chlorophyll-rich) parent. This striking cultivar originated as a sport on 'Green Arrow' and has a similar form. Due to the narrow form, in larger gardens it is possible to plant 'Sparkling Arrow' in groups of three, as in the photo above. There are other variegated Nootka, but they are not very readily available in the trade.

Closeup of foliage, Cupressus nootkatensis 'Gabriel's Gift'

'Gabriel's Gift', a Buchholz & Buchholz selection, has variegation that is more dramatic, not as regular, and whiter than 'Sparkling Arrow'. If you are looking for a show-stopper and you happen upon it, snap it up! The large white sections will burn in full sun, especially when the tree is newly planted, so locate it where the young plant gets some afternoon protection.

Cupressus cashmeriana in a Mediterranean Zone 9b garden

There is no more lovely, graceful cypress than Cupressus cashmeriana, which, despite its name, is native to Bhutan, not Kashmir. But for two considerations, it is worthy of inclusion in almost any landscape. The two considerations, however, are deal-breakers: it gets enormous, and it is only hardy to Zone 9. However, if you have the room and you are in a mild climate, nothing should hold you back. Its weeping branches undulate in the breeze and its blue-green color is compatible with virtually any other. Native to a monsoonal climate, it nonetheless does very well with moderate irrigation in a typical garden. In the garden pictured above, it is the anchor in a bed containing palms, acacias, madrone and yuccas. It is possible that its roots have commandeered all of the water afforded to the bed, leaving just enough for its water-thrifty companions.

4. Cupressus macrocarpa 'Chandleri'

Pollen and seed cones of Cupressus cashmeriana

Chandler's Monterey cypress in a Northern California garden

This narrow, upright deep, deep, rich green selection of Monterey cypress is a garden marvel. While it takes up far less real estate than Kashmir cypress, it, too, is only hardy to Zone 9. However, if you can grow it, its color and its slender silhouette make it one of the best 'punctuation marks' in almost any style of garden. Less dramatic than the Nootka cypress, it is easier to work with as it doesn't demand the same level of attention, and tends to show its near neighbors to their best advantage. When we look for interesting plants to add to our gardens, we have a tendency to focus on unusual colors, and gravitate to blues, yellows, golds and variegated foliage. It's a mistake to not seek out intense greens as well. This is one of the best.

Cupressus macrocarpa 'Greenstead Magnificent' in a Northern California garden

Greenstead Magnificent Monterey cypress is truly magnificent, mostly because its foliage is a soft, seafoam green, a color that is not found on any other conifer. There are junipers that are close, but not quite... The pastel green is loveliest in spring, when the new twigs emerge with a pinkish hue. It is an effect that photos cannot hope to depict; you simply have to see for yourself! This cultivar is, unfortunately, only hardy to Zone 8 and does not much like humid summers. While we try not to suggest cultivars that are hard to grow and even harder to come by, we include this one because of its unique coloration and because it is one of the few cypress (maybe the only, other than its parent), that is horizontal and spreading in habit.

Coneybears' golden cypress in a SF Bay Area garden

Like Cupressus cashmeriana, 'Coneybearii Aurea' needs a lot of room. Its height is impressive (the ACS classes it as 'large', meaning that it grows over 12 inches (30 cm) per year) and its breadth equally so. However, if you are in Zones 8 to 10 and have the room, it's one that should be seriously considered. This cultivar is a trifecta: it 'improves' on the species in three ways. It is golden in hue, weeping in habit and has threadleaf foliage, making for a stunningly eye-catching, graceful tree. It is particularly noteworthy in winter, when it lights up gray days like a beacon.

Blue Ice Arizona cypress used as a tall hedge in a Northern California garden

For those of you getting frustrated because many of the selections thus far have not been hardy in much of the US, you will be pleased to learn that Arizona cypress is hardy to zone 6. Not only is it cold-hardier than many Cupressus, but Cox and Ruter, in their definitive Landscaping with Conifers and Ginkgo for the Southeast, pronounce success with Arizona cypress in that region; it understandably flourishes in areas with drier summers and cooler nights. While there are a number of blue cultivars of this species, we've chosen 'Blue Ice' due to its pleasing, slightly open form and light, silvery, powder-blue needles. Other attractive cultivars with slightly different growth habits and shades of blue are 'Blue Pyramid', 'Carolina Sapphire' and 'Chapparal'.

While it shares its growth habit with 'Blue Ice', 'Sulfurea' has its own, distinctive color. Its needles are tipped with a sulfury yellow new growth, which gives the entire plant a whitish/pale yellow cast. A standout in the garden, especially when paired with deep greens or maroon foliage.

9. Cupressus × leylandii 'Gold Rider'

Closeup of foliage of Cupressus arizonica var. glabra foliage, showing distinctive coloration

Cupressus × leylandii 'Gold Rider' is widely considered to be one of the best golden conifers

Cupressus × leylandii, or Leyland cypress, now known to be a naturally-occurring cross between Cupressus nootkatensis and Cupressus macrocarpa, has a somewhat checkered reputation, which you can read about at the link above or Google for more horror stories. However, when planted appropriately (it is hardy to Zone 4) and not shoe-horned in where there is not room for it to grow, it can serve as a good garden citizen. This is particularly true of the cultivar 'Gold Rider', which has a uniform golden color, especially vibrant when new growth pushes in spring. Cox and Ruter recommend it for zones up to 8a in the Southeast, and it performs well in most other parts of the US. Used as a focal point, this selection will have none of the problems associated with the massive hedges of the original hybrid, particularly in the United Kingdom.

One of the few truly dwarf cypress: Cupressus sempervirens Tiny Tower®. Photo by Monrovia Nursery.

The ACS rates this selection as hardy to Zone 8, but Cox and Ruter finds that it survives nicely in Zone 7a. It is a Monrovia nursery introduction, registered as Tiny Tower, with the botanical name of 'Monshel'. It is a wonderful choice for those with smaller gardens as it grows much, much more slowly than the species and after 10 years is generally only about 8 feet (1.6 m) tall and only 1 foot (30 cm) wide. This cultivar is well-suited to containers as well as in-ground planting.

Want to know more about cypress and how to grow them? Join the ACS and ask the experts, attend meetings and participate in our on-line forums.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

Updated: Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Intermediate Conifers: Creating Variety in your Garden

By Web Editor

December 7, 2019

Looking to spice up your landscape? Find out more about “the forgotten conifers.”

In the two most recent installments of Conifer Corner, I’ve been discussing outstanding conifers in each of the four size categories recognized by the American Conifer Society (ACS), beginning with the smallest size category (Miniature conifers) and working up to larger conifers. In this edition of Conifer Corner, I continue this discussion by considering Intermediate conifers.

The ACS defines intermediate conifers as those that grow 6-12” per year and reach a height of 6’ to 15’ at age 10. They are not adorable little miniatures or dwarfs that can fit into a container or rock garden. Conversely, intermediates won’t dominate a landscapeas a specimen, like a large conifer. Nevertheless, intermediate conifers are an important group of trees because they fulfill an important function in landscape design and development.

Unlike their smaller cousins, miniature and dwarf conifers, intermediate conifers are less likely to get “lost in the shuffle” in a busy landscape design. Unlike large conifers, intermediates are less likely to interfere with power lines or other overhead obstruction and are better suited to planting closer to houses and allow greater flexibility in site selection.

As with all of the trees that I’ve discussed in this series on conifers in the ACS size classes, there is considerable variation in growth depending on site and cultural practices. This is especially true with intermediates. Some intermediate conifers growing on a good site could reach a size comparable to large conifers.

There is no single “official” trial garden where conifer sizes are determined. Size classes are based on observations by growers and conifer enthusiasts and a given cultivar may be listed as an intermediate in one reference and as a large in another. In general, size classes referred to in Conifer Corner articles are based on the ACS Conifer Database.

Intermediate Conifers for the Central Region

Pinus cembra ‘Silver Sheen’ Swiss stone pines

are reliable conifers in Michigan landscapes

Pinus cembra (Swiss stone pine)

Conifer expert Chub Harper has a passion for plants that is matched by few and few plants get him as excited as Pinus cembra. Just mention Pinus cembra and Chub goes all Will Rogers. “I’ve never met a cembra I didn’t like," Chub enthuses. “This is one of those plants I just don’t understand why we don’t use more.” Indeed, it’s easy to understand Chub’s swooning for Swiss stone pine. This species maintains a tight compact form with a straight single leader, giving it a stately elegance without pruning.

Moreover, Pinus cembra has beautiful blue green needles that often take a silvery sheen. Cembra is fairly tolerant of a range of sites and is variously listed as zone 3 or 4, so it is hardy in most of the Lower Peninsula. Pinus cembra is one of those plants that even the straight species is distinctive enough tomake an impression. In addition, there are a number of cultivars on the market. Note that some of the cultivars included here fit into the Dwarf size class.

.

- Pinus cembra ‘SilverSheen’

A striking cultivar of P. cembra with silvery blue needles. Zone 5.

- Pinus cembra ‘Chalet’

A pyramidal to upright form of Pinus cembra. There is a terrific specimen in the Harper Collection. Zone 4, though also reported to Zone 3.

- Pinus parviflora (Japanese white pine)

A solid performer in Michigan. There are a variety of cultivars of Japanese white pine, some of which I’ve mentioned in earlier Conifer Corners.

- Pinus parviflora ‘Bergman’

This is one of the more striking forms of Japanese white pine, with twisting bluegreen needles. Variously listed as a dwarf or an intermediate.

- Pinus parviflora ‘Fukuzumi’

The formon this plant can be variable, but its recurved blue-green twisted needles give it consistent appeal.

The color and texture of the conifer, Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Filifera Aurea’ make it a show-stopper.

Golden thread falsecypress (Chamaecyparis pisifera 'Filifera Aurea’)

welcome visitors to the Harper Conifer Collection at Hidden Lake Gardens. Photograph by Jack Wikle

Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Filifera Aurea’ (Golden thread false cypress)

Yes, the Latin name is a mouthful, but this plant is a show-stopper like few others. ‘Filifera Aurea’ generate interest from a distance due to their bright yellow color and upright weeping form, as well as up close due to their impossibly long threadlike foliage.

Abies concolor ‘Conica’ is a striking upright form of

concolor conifer that is well adapted in Michigan

Abies concolor ‘Conica’

Continues the theme of color – this time striking blue. Abies concolor ‘Conica’ also continues the theme of underused conifers. This tree’s stately upright form makes it a prime choice as a specimen plant. Put one of these in your yard and you’re guaranteed to have all of the neighbors asking “Whatzzat?”

Picea glauca ‘Pendula’

Technically this is listed as an intermediate, but on better sites it may push toward the large category. Also, this cultivar has been around long enough that it’s possible to find some decades-old larger specimens. The tight form and drooping branches make it easy to envision this plant in a snow-blanketed mountainside.

Abies koreana ‘Silberlocke’

Gets double marks for showmanship. The needles on this cultivar of Abies koreana are highly recurved, that is, they are turned upward to reveal their silvery underside. While that alone is enough to give the tree tremendous ornamental appeal, ‘Silberlocke’, like most Korean firs, also produces prodigious amounts of colorful cones. Although cones on firs make Christmas tree growers cringe, in this case it adds to the plant’s landscape appeal.

Need a break from“blue spruce burnout”? Abies lasiocarpa ‘Arizonica Compacta’

has outstanding conifer form and color

Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica (Corkbark fir)

An argument for the lumpers and splitters. Some references list this as a variety or even sub species of Subalpine fir (A. lasiocarpa) while others (for example, the Gymnosperm database) list corkbark fir as its own species (A. bifolia). In the nursery trade, var. arizonica holds sway. Another high elevation conifer from the mountain southwest, corkbark fir is a striking tree that can often match Picea pungens for blue color.

Larix kaempferi provides a dramatic contrast in conifer form and color

Larix kaempferi ‘Pendula’

Deciduous conifers always make a unique contribution to the landscape and this weeping larch is no exception. This plant commands interest anytime during the growing season, but especially in the early spring when the new bright green needles are just beginning to flush. According to the ACS, this tree is widely mislabeled as Larix decidua ‘Pendula’.

The yellow highlights of the conifer, Picea pungens ‘Walnut Glen’

can brighten up even a dreary fall day in Michigan

Picea pungens ‘Walnut Glen’ (Walnut Glen Colorado blue spruce)

Is an interesting twist on the old standby, Colorado blue spruce. This P. pungens cultivar has a golden cast to its needles, which often make it look like the sun is shining on it even when it’s in the shade. Reportedly adapted to a fairly wide range of site conditions though the variegated yellow needles may suffer scorch under stress.

Pinus aristata (Bristlecone pine)

We can’t really recommend bristlecone pine as an outstanding grower in Michigan, but it’s a fascinating tree and it will grow on suitable sites here in Michigan. In their native habitat, bristlecone pines are among the oldest living things on earth. The Rocky mountain form (P. aristata) can live to nearly 3,000 years old and specimens of the Great Basin form (P. longaeva) have been found that are over 4,800 years old. Although we don’t expect a Bristlecone pine to live thousands of years in Michigan (and, in any case, we won’t be around to see it), this makes an interesting specimen in the right spot. Look for a site with good drainage and relatively good air flow. Like many trees adapted to the arid west, these pines don’t like wet feet or high humidity.

Columnar conifers such as Thuja occidentalis ‘Degroot’s Spire’ are especially

dramatic when grouped for effect

Thuja occidentalis ‘Degroot’s Spire’

In general, arborvitae are the kinds of plants that don’t usually get people too excited. However, this upright columnar form makes a great accent and can add a formal appearance as a border or can be grouped for effect.

Thuja occidentalis ‘Hetz Wintergreen’

Another upright form of arborvitae. ‘Hetz Wintergreen’ is noteworthy for a couple of reasons. It tends to maintain its green color throughout the winter when many other conifers turn off-color and it tends to maintain a strong central leader, whereas many columnar arbs can develop multiple leaders or bend over under snow loads. Excellent for a year-round screening hedge and windbreak.

Picea omorika ‘Pendula Bruns’ (Weeping Serbian spruce)

It’s always hard to go wrong with a Serbian spruce. ‘Pendula Bruns’ is a little slower growing and has a little tighter form than ‘Pendula’and ‘Berliners Weeper’ – more on those two in the next Conifer Corner.

Picea glauca 'Densata’ (Blackhills spruce)

Depending on the reference, Black hills spruce is listed as either a true botanical variety (var. densata) or simply as a cultivar. Regardless of the taxonomy, this is a versatile tree that we’ll likely see more of in the future. As the Latin name ‘Densata’ implies, Black hills spruce has a tight, dense growth habit and maintains a nice pyramidal form. Its growth rate is slower than the straight species or blue spruce so it’s less likely to get out of hand and provides more flexibility in site selection. With its uniform compact growth, Black hills spruce also shows promise as a table top Christmas tree.

Text and photographs by Dr. Bert Cregg. Additional photograph by Jack Wikle.

Dr. Bert Cregg is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Horticulture and Forestry at MSU.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Fighting Conifer and Evergreen Insect Pests

By Gerry Donaldson

November 13, 2019

Get to know the common invasive species in conifers: the hemlock woolly adelgid and Asian longhorned beetle.

The life stages of the Asian longhorned beetle, a conifer insect pest.

Photograph by Kenneth R. Law, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org

In the 2017 Fall Issue of Conifer Quarterly, we looked at the threat invasive species pose to our environment and some of the economic costs. We also discussed our experience with some invasive species, and the importance of early detection if we are going to be successful in controlling, suppressing or, preferably, eliminating new invasive species. This article focuses on two invasive species that can affect a very large geographic area of North America.

The Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA)

The hemlock woolly adelgid, an aphid-like pest in conifers.

Photograph by Bruce Watt, University of Maine, Bugwood.org

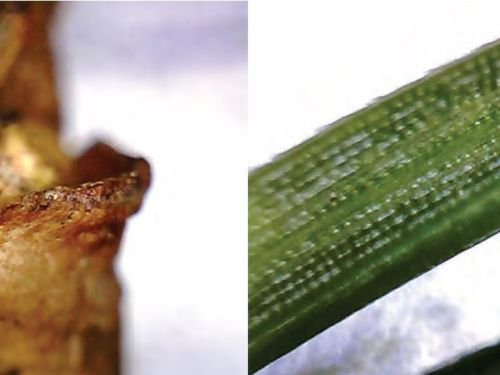

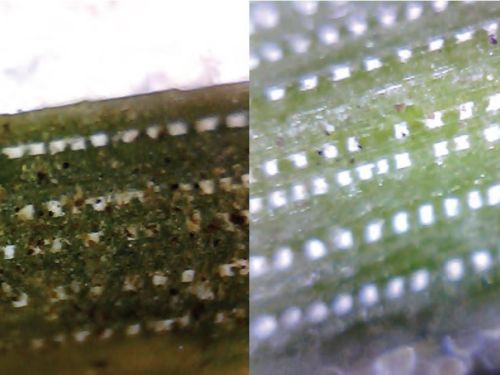

Hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) was first reported in the eastern U.S., in Virginia in the 1950’s. Feeding on the sap of hemlocks, HWA increases in numbers until the health of the tree declines, the needles drop, and the tree dies. This can take as little as two years.

The range of HWA is now Maine to South Carolina and west into Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky and Tennessee, with an expansion rate of about 15 miles per year. Both northern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) and Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana) are preferred hosts for the woolly adelgid, which has now killed tens of thousands of trees. In some areas, over 80% of the native hemlocks have been killed.

DNA evidence indicates the HWA found in eastern North America likely came from Japan, not from the western U.S. Hemlock woolly adelgid was first reported on western hemlock (Tsuga heteropyhlla) in the 1920’s. Western hemlock and mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) appear to be resistant to HWA. Some spruces (Picea) of Asian origin are reported to be alternative hosts, but seldom are.

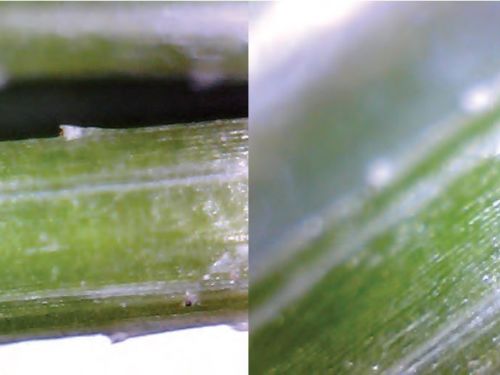

A close up of the hemlock woolly adelgid.

Photograph by Bruce Watt, University of Maine, Bugwood.org

Winter is the best and easiest time of the year to see hemlock woolly adelgid. Simply look at the base of the needles, where they meet the twig, for the distinctive white tufts. If you are monitoring in mature forests with large hemlock trees, binoculars can be helpful. If you are in an area that does not have an established population, and you discover HWA, please take photos and inform your state Department of Agriculture, the Sentinel Plant Network, or the National Plant Diagnostic Network.

In many areas, hemlocks are under quarantine and cannot be moved unless certified to be adelgid-free. Please respect such quarantines and prevent the more rapid distribution of hemlock woolly adelgid.

The Asian Longhorned Beetle

An adult Asian longhorned beetle, another invasive pest in conifers.

Photograph by Eugenio Nearns, USDA/APHIS/PPQ

National Identification Services (NIS), Bugwood.org

Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) is a more recent introduction to North America, first identified in the U.S. in 1996. Asian longhorned beetle has been discovered and suppressed many times in areas including Chicago, Illinois, New York City, Cincinnati, Ohio, Boston, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. The introduction of ALB is usually associated with solid wood packing materials from Asia, and the beetle can be moved in logs, firewood, and other wood products.

Asian longhorned beetle attacks at least 18 species of hardwood trees, including maple, birch, horse chestnut, poplar, willow, elm, ash, and black locust, with maples the preferred host. ALB attacks both stressed and healthy trees. Tree mortality is the most readily identifiable symptom, but bark cracks and branch dieback usually are apparent before death.

Damage caused by the Asian longhorned beetle.

Photograph by Daniel Helms, The Ohio State University, Bugwood.org

Female adult ALB lay eggs in divots they chew in the bark. Larvae develop in the sapwood and then move into heartwood where they mature into adults. The sapwood feeding interferes with xylem and phloem transport of the host trees, eventually resulting in the death of individual branches or the entire tree.

Emerging adults leave distinctive holes about 3/8 inch in diameter, a little larger than the diameter of a pencil. Exit holes can be virtually anywhere on the tree and can number in the hundreds. The adults emerge usually between June and October. While seldom seen unless the host tree is cut, larvae are yellowish-white grubs of up to 2 3/8 inches long and of up to 3/8 inch wide.

Adults beetles are very large, from one inch to one and one-half inches long and have banded black and white antennae at least as long as their bodies, and usually longer. The body is shiny-black with white spots. In some regions of North America, there are other borers that can look similar. Capturing an adult and providing it to the National Plant Diagnostic Network is the best way to affirm its identity.

Fighting Conifer Insect Pests as a Community

You can help in monitoring for invasive insects by being aware of what is happening in your garden. If you see something that looks suspicious, take a photo and then contact a Sentinel Plant Network member garden for help in identifying the insect or disease. The USDA provides additional information, educational modules and trainings at https://firstdetector.org/.

To learn more about either hemlock woolly adelgid or Asian longhorned beetle, please call any of the Sentinel Plant Network member gardens of the American Public Garden Association, or visit www.bugwood.org.

Click here to learn how to control conifer pests, or here to read more about other conifer pests like the parasitic wasp and the Siberian silk moth.

The Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia provided much of the information for this article.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Monday, June 5, 2023

Updated: Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Evergreens and Companion Planting

By Dave Resavage

February 22, 2020

Find companion plants for your evergreen conifer garden to add a splash of color and texture!

A companion plant, Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla ‘David Ramsey’)

Photo:Eaton Farms / Pennsylvania Pride Trees

Conifers, most of which are evergreens, naturally make great neighbors to ornamental companion plants in the garden. Many novice gardens and homeowners embarking on a new garden design or landscape renovation are unaware of the magic conifers will bring to their schemes when combined with their favorite ornamental flowering shrubs, trees, perennials, grasses, and even tropical plants, such as bananas! The horticultural marriage between evergreen conifers and companion plants can ensure years of gardening bliss when thoughtfully arranged.

Combining Conifers and Companion Plants

The vast array of conifers and companion plants offered in the market today make it possible for harmonious, interesting, and dramatic garden designs. Particular attention must be paid to size, scale, and growth rate of companion plants. If ignored, unwanted consequences and disappointment may ensue.

It would be foolish to invest time and money into a rare and unusual conifer and to plant it directly next to your favorite shrub or tree companion, only to see it become quickly outgrown by its companion, causing irregular growth for both plants!

Scale and maturation of companion plants is essential to achieving a visually pleasing garden of mixed arrangement. Beginning gardeners in the planning stage should allow ample room for growth between their conifer specimens and companion plants. Some plants, especially woody ornamentals and perennials, are notorious for growing larger than the printed information tag accompanying them.

The companion plant, the Blue Holly (Ilex x meserveae ‘Honey Maid’)

Photo: Eaton Farms / Pennsylvania Pride Trees

Luckily, most can be moved with minimal effort in an immature garden. Gardeners with overgrown, or mature gardens, sometimes are faced with plants of questionable ornamental value, and they are best advised to make one final pruning at the trunk base and begin again.

I have found myself in this difficult situation; faced with the task of removing the old in order to make room for the new and exciting, then finally arriving at a happy conclusion that most times the removal was for the best, as a garden landscape is ever changing.

Many new plants offered today, both conifers and companion plants, are far superior to the cultivars of yesteryear and new additions to the garden can be a welcome breath of fresh air, especially in a mature garden. Broadleaved evergreens, such as rhododendron, also make good companion plants for conifers.

Conifers and Woody Ornamentals Combinations

Since evergreen conifers afford texture and year-round color, woody ornamentals, like trees and shrubs are natural companion plants with their seasonal changes in appearance. Always bear in mind their ultimate size and mature visual appearance next to their conifer neighbors.

It only takes one visit to a well-stocked nursery to realize that your only limit when choosing companion plants is your imagination. (I don’t like to say budget is a limit when choosing garden plants because plants, unlike most other purchases, will GROW! You can always buy smaller plants, just be patient and offersome extra TLC with young plants.)

While at your favorite nursery, look for what is currently in bloom, but also be attentive to how the plant will look later in the season, after the flowering period is complete. Many woody ornamentals add great winter interest to the garden with colorful stems, heavily textured bark and unique branching structure.

A conifer complement, the Golden Hinoke Cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Crippsii’)

Photo: Eaton Farms / Pennsylvania Pride Trees

Additionally, old garden favorites are now offered in variegated and all golden foliage forms, such as the hardy blue holly (Ilex x meserveae ‘Honey Maid’)! This spectacular new variegated evergreen holly, offering a dark green leaf outlined with a rich golden margin, is very hardy. It makes an outstanding complement to bluish colored conifers, especially during the winter months.

The lush, blue, purple and lavender colored flowers of Hydrangea macrophylla ‘Endless Summer’ or Hydrangea macrophylla ‘David Ramsey’ when combined with a golden conifer, such as Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Crippsii’ or Taxus cuspidata ‘Dwarf Bright Gold’ can transform the sunny summer garden into a visual explosion of color!

Best of all these two new big leaf hydrangea cultivars are repeat bloomers, June through October, and will reliably produce flowers every year, even after a harsh northeastern winter. They produce flowers on both old growth and new woody stems, thus ensuring outstanding flower display.

Equally, the shady summer garden can be brightened up with the unusual pairing of the shrubby form, leathery-leafed, evergreen Aucuba japonica ‘Variegata,' combined with such mounding/prostrate conifers, as Taxus baccata ‘Repandens’ or Cephalotaxus harringtonia ‘Duke Gardens.'

Those gardeners with restricted space who desire a small spring flowering tree, would benefit from the association of the pink flowering Cercis canadensis ‘Forest Pansy’ with Picea pungens ‘Procumbens’. The new, bluegreen flush of growth on the picea, combined with the rich crimson leaf color of the cercis, make for an unforgettable spring show, guaranteed to only improve with each passing season!

With so many trees and shrubs available, the association between conifers and woody companion plants is endless. Woody ornamentals will provide seasonal colors and textures, but rely upon the conifers to continue the show year round. Be creative, look for interesting attributes that will give woody companion plants year round appeal with your conifer gems!

A companion plant, the 'Forest Pansy' Redbud (Cercis canadensis ‘Forest Pansy’) Photo: Eaton Farms / Pennsylvania Pride Trees

Perennials, Grasses, and Tropical Plants with Conifers

A garden consisting of only woody ornamentals and conifers would be pretty but sometimes not visually interesting. When associating perennials, grasses and YES, even tropical plants with conifers and woody ornamentals, a garden is yet again transformed, taking on an added dimension of depth, scale, and drama.

With limited space in this article, I can only offer some interesting suggestions utilizing these associations in the garden. But again, the same rules apply. Always be mindful of mature plant size and scale.

Perennials and grasses are best used in mass plantings if space permits. They should be at the very least displayed in groupings; odd-number groups seem to work best. A garden design consisting of too many different single selections looks busy and visual clutter in the garden should be avoided.

A great contrast plant in the garden, especially when used in groups or mass plantings, is Heuchera, commonly known as coralbells. This plant has seen an explosion of cultivars in endless colors recently. Heucheras work well planted in mass groupings and used as a boarder edging in the semi-shaded garden.

The companion plant, Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis ‘Flow’)

Photo: Eaton Farms / Pennsylvania Pride Trees

Heuchera ‘Caramel’ offers a rich, bronze orange color, guaranteed to get noticed in the garden. Plants from the genus Hemerocallis, commonly known as daylilies, might be considered an old standby but are now being offered in endless color combinations.

Many new varieties exist with extended bloom periods and repeat bloom cycles; these new cultivars are not your grandmother’s daylilies! Some new cultivars can be a bit pricey but are well-worth the investment for their unusual colors and high performance. Additionally, most are tough, enduring garden perennials, which do well in full-sun or semi-shade.

A favorite grass-like perennial of mine that works well in both sun and shade is Liriope muscari ‘Variegata.' This plant has endless uses, from being planted en masse as a groundcover to utilization as a wispy edging/border plant. It combines well with conifers and perennials alike, growing only about 12 inches to 15 inches in height. The colorful variegated leaves endure well into early winter, making it a hardworking plant, worthy of garden space.

A true dwarf grass with vibrant golden color, making a splash in the shady and semi-shaded garden is Hakonechloa ‘Aureola’. This garden grass combines perfectly with hostas and ferns in the shady/semi-shaded garden and is tolerant of dry soils. A graceful grass with arching bright yellow blades, it looks great when paired with a conifer such as Cupressus nootkatensis ‘Pendula.'

A few years back I started toying with the idea of adding tropical plants to my northeastern Pennsylvania garden, and after some research, I discovered that my idea was well within the grasp of my garden design, even though I commonly experience winter lows typically around zero degrees Fahrenheit.

A true hardy tropical perennial is the Musa basjoo, commonly referred to in the garden world as Japanese fiber banana. This exotic banana will grow easily to 10-feet tall or more in a single season. Large dramatic light green leaves up to 6-feet long are sure to make a few heads turn. The large leaves combine well with other intermediate and large conifers, such as Cedrus atlantica ‘Fastigiata,' as I have done in my own garden.

The Nootka cypress (Cupressus nootkatensis ‘Pendula') with Hakone Grass (Hakonechloa 'Aureola')

Photo: David Resavage, from a landscape renovation he designed

Minimal winter protection in the fall ensures this large growing tropical will return year after year. Simply cut the banana stalks down to about 6 inches tall after the first frost. Cover the stalk completely with deep hardwood mulch or use leaves. I construct a simple cage around the stalks and surrounding root zone before filling with leaves at least 15 inches to 18 inches in depth.

In early May, I remove the mulch/leaves and witness the banana returning from the dead! Try this and by late June your banana will be taller than you and well on its way to giant proportions creating major garden drama! Be creative in your garden design and plant associations as the plant selections offered today are endless. Be on the lookout for new and up-and-coming plants, which are always being marketed.

Try new selections and don’t be afraid to make changes to your garden. A garden design is never truly complete because in order for a garden to stay fresh and alive, changes inevitably have to be made.

The Japanese fiber banana (Musa basjoo) with

Fastigiate Atlas Cedar (Cedrus atlantica ‘Fastigiata’) and

Variegated Lily Turf (Liriope muscari ‘Variegata’)

as an edging plant at the Resavage garden in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania (zone 6a)

David Resavage is a professional landscape designer possessing an abounding love of conifers, tropicals, and any plant deemed rare or unusual. After pursuing an academic career in landscape design and ornamental horticulture, he began actively pursuing, studying and utilizing the most unusual, rare and dramatic landscape plants in his designs.

He has traveled extensively throughout the British Isles, Canada and the Caribbean researching and observing native and ornamental plantsin relation to garden design. He divides his time between his home-based ornamental specimen garden in Wilkes-Barre, and a more natural woodland garden at his summer home on Sylvan Lake, about an hour outside Wilkes-Barre.

His gardens have been repeatedly featured in local periodicals for their unusual and noteworthy design style and provocative use of plant materials. He is the chief landscape designer for Hanover Nursery in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By administration,

Monday, June 5, 2023

Updated: Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Web Editor

May 31, 2021

10 Types of Pine Trees that Everyone Should Know 10 Types of Pine Trees that Everyone Should Know

Pinus mugo var. pumilio cultivar

What is a Pine Tree?

Many of us have a tendency to refer to all conifers as pine trees, which is not illogical considering that the pine family (Pinaceae) is the largest family of conifers and accounts for approximately ¼ of all cone-bearing trees (the definition of a conifer is a plant that bears cones). However, those roughly 200 species in Pinaceae include not just pines, but firs, spruces, cedars, hemlocks and larches. Most Christmas trees sold in this country are firs or spruces, despite the fact that they are often referred to as pine trees. To truly be a pine tree, a conifer must belong to the genus Pinus.

Pinus lambertiana (sugar pine) growing in the southern California mountains

Wild-growing pines quickly become too large for all but the grandest gardens, as the photo of the sugar pine demonstrates, although amongst the approximately 100 recognized species in the genus Pinus there are many trees with attractive features. The key for gardening successfully with pines is to choose among the thousands of dwarf pine cultivars. A cultivar, short for ‘cultivated variety’, represents a selection that was chosen due to its slower growth rate, dwarf form, unusual color, weeping habit, etc. It’s in the world of cultivars that you can find attractive, tough, interesting, structural choices to enhance your garden’s year-round beauty.

10 of the best pines for gardens and one to avoid

1. Pinus densiflora ‘Low Glow’

Close up showing branching and trunk

Low Glow Japanese red pine (USDA zone 5) has a spreading habit, lush green needles and when mature, reddish textured bark. It is slow-growing and well-behaved, requiring little pruning or special care. The specimen above is pruned regularly to open the crown and expose some of the trunk and branching, but it is not necessary, as the photo as the link demonstrates.

2. Pinus mugo (mountain pine or mugo pine) cultivars

Pinus mugo 'Jakobsen' is attractive in the landscape or in containers

The ACS recognizes almost 80 cultivars of this species, commonly called mugo (pronounced ‘moo-go’, not ‘mew-go’) pine or mountain pine (USDA zone 3). Mugo pines are probably the pines most often seen at mainstream nurseries and big box stores, and are often deemed unexciting by amateurs and aficionados alike. Mugos are some of the toughest conifers out there, native to the windy mountains of central Europe they are accustomed to eking out an existence in a tough environment. But there is also beauty and drama lurking in this widely variable and misunderstood species! Take the ‘Jakobsen’ mugo pine above: it naturally develops an open and interesting architecture, requiring no pruning to provide a structural garden focal point. Its deep green needles lend richness and depth to the landscape. It is a wonderful choice for a container, as well, and works beautifully in a rock garden.

Pinus mugo 'Schweitzer Tourist'

There are quite a few golden mugo pines, in addition to 'Schweitzer Tourist', ‘Carstens’ is an excellent low-growing selection, as is ‘Sunshine’. Others, such as ‘Ambergold’ or ‘Winter Sun’ grow to become quite vertical in habit.

Pinus mugo 'Winter Sun'. Photo by Janice LeCocq

3. Pinus parviflora (Japanese white pine) cultivars

Pinus parviflora 'Fukuzumi'

The Japanese white pines (USDA zone 5) are well-formed, elegant plants, with soft, delicate needles that are often streaked with white, blue or gold. These cultivars also have some of the most stunning pollen cones in the conifer world. They are not as tough as the mugos but with good drainage and a bit of afternoon shade in hot areas, they perform well in garden settings. 'Fukuzumi', pictured above, has a naturally windswept habit and rich blue-green needles. This specimen has never been pruned.

'Tenysu kazu', also known as 'Goldylocks', is a stunning selection, with creamy-golden new growth.

As if the soft, fluffy needles and elegant habit were not enough, Japanese white pines sport some of the most dramatic and eye-catching male (pollen) cones in coniferdom. Check out those on Pinus parviflora 'Cleary':

Pinus parviflora 'Cleary' pollen cones - a pine with attitude! Photo by Janice LeCocq

Pinus parviflora 'Bergman' pollen cones

4. Pinus banksiana 'Uncle Fogy'

If the Pinus parviflora cultivars are some of the most elegant pines, 'Uncle Fogy' clearly has to be one of the most ridiculous. This cultivar of Pinus banksiana (USDA zone 2) is twisted, alternately weeping and upright and no two look the same.

Pinus banksiana 'Uncle Fogy'. Photo by Janice LeCocq

Pinus banksiana, or jack pines, grow more irregularly in nature than many other pine species. 'Uncle Fogy' just happens to be one of the most wildly irregular of all, growing sometimes upright for a while and then flopping to the ground and then often continuing upwards again. One of the best cultivars for pruning and shaping, you can make your 'Uncle Fogy' unique to your family! Jack pines are tough plants and once established require low water and little care. There are other attractive cultivars in this species, such as 'Manomet' and 'Angell'.

5. Pinus jeffreyi 'Joppi' (Joppi Jeffrey pine)

California has more native conifers than any other state, but many of them have no, or few, cultivars. Luckily for coneheads, one of the best-loved natives, Pinus jeffreyi, (USDA zone 8)has a lovely, compact cultivar called 'Joppi'.

Pinus jeffreyi 'Joppi' after some interior pruning

While the wild species can reach 80-120' at maturity, 'Joppi' is very well-behaved in a garden setting. The specimen above has been in the ground for six years, after being planted from a 20-gallon container, and is approximately five feet tall. The long, stiff needles are a wonderful contrast to lighter foliage and its strong structure adds an architectural element.

6. Pinus strobus cultivars

Like Pinus parviflora, Pinus strobus, or eastern white pine (USDA zone 3), is a soft, five-needled pine, and also has elegant attributes. Like Pinus mugo, there are many choices of cultivars, with a wide range of habit, color and shape. The ACS recognizes well over 100 P. strobus cultivars, making this species one of the most garden-friendly of all conifers. We'll recognize two cultivars here, wildly different in size, habit and color.

Pinus strobus 'Blue Shag', a name that needs no explanation

'Blue Shag', pictured above, is true to its name with its glowing blue-green needles and shaggy demeanor. If left alone, like this one, it is attractive if somewhat unruly. Those wishing a more sedate look can prune at will as the plant, which does not develop a central leader, tolerates pruning well.

And for a completely different look, Pinus strobus 'Pendula'

However, my favorite Pinus strobus cultivar is 'Pendula', which is sort of like a big, bad cousin to 'Uncle Fogy', albeit more graceful. This cultivar is not for small gardens and not for those wishing an orderly, regimented look. LIke 'Blue Shag', it takes well to pruning and can be tamed (or made wilder!) if so desired.

7. Pinus sylvestris (Scots pine) cultivars

If I had to pick my favorite species of pine it would have to be Scots pine, or Pinus sylvestris (USDA zone 3). I just love the flat, blue-green needles on the majority of the cultivars and their neat, compact habit.

Pinus sylvestris 'Watereri' is a lovely, slow-growing selection with rich blue-green needles

Close up of 'Watereri' needles, buds and cones

However, if you prefer golden foliage, Pinus sylvestris does that, beautifully, too! 'Nisbet's Gold' is one of the best gold conifer cultivars of any species, and, like many of the other sylvestris cultivars, has a tidy habit and is relatively slow-growing. With sufficient irrigation, this golden conifer does not burn in full sun, even in my zone 9b location.

Pinus sylvestris 'Nisbet's Gold' lighting up the winter garden

There are dozens more Scots pine cultivars to choose from. Take a look and maybe like me, you'll fall in love!

8. Pinus nigra 'Oregon Green' (Oregon green Austrian pine)

Like mugos, Austrian pines (USDA zone 4) are one of the classsic old-world, 'hard' pines, so termed due to their relatively hard wood (although to keep things confusing, all conifers are known in the timber industry as 'softwoods'). They have very deep green, stiff needles and often a graceful natural form. When pruned they make marvelous focal points. My favorite is one of the larger cultivars, 'Oregon Green'.

Pinus nigra 'Oregon Green' branches on the left. Photo by Janice LeCocq

9. Pinus koraiensis (Korean pine) 'Dragon's Eye' or 'Oculus Draconis'

Korean pines are hardy (USDA zone 3), durable and very pretty. Most have curling needles, often with variegation. 'Dragon's Eye' is an upright cultivar, occupying a small footprint that makes it suitable for small gardens.

Close up of variegated foliage on 'Dragon's Eye'

10. PInus wallichiana 'Zebrina'

Although last on the list, Zebrina Himalayan pine is one of the very best! All Himalayan pines have long, graceful needles, but Zebrina does it one better by striping them with pale yellow. The landscape effect is breathtaking, especially in winter's soft light.

Pinus wallichiana 'Zebrina', strutting its stuff in the landscape. Photo by Janice LeCocq

Those are, in my opinion, 10 of the very best pines for a garden landscape. But I promised at the start that I would give you one to avoid: Pinus thunbergii 'Thunderhead' (USDA zone 5). Why do I feel so strongly about its negative characteristics that I feel the need to note it here? Because 'Thunderhead' has just about the deepest, richest green needles of any conifer, and in spring it produces copious, white candles (new shoots) that contrast dramatically with the foliage. It's almost impossible to resist. So desirable is this cultivar that it is now turning up everywhere, even at nurseries that have very few conifers to offer.

Springtime candles on Pinus thunbergii 'Thunderhead'. Photo by Janice LeCocq

So if it is so lovely and dramatic, what's the problem? It's a thug! Most cultivars grow more slowly than the species. This one actually outpaces it! If you do nothing, this lovely little plant very rapidly becomes an enormous woolly bear. Of the original three that I planted, I am down to one and it gets pruned vigorously twice a year by an expert. If you are aware of Thunderhead's shortcomings, plant with impunity, but I have seen more disappointment (and disgust) associated with this cultivar than any other, partly due to the display that it receives in the retail trade.

Those are my favorite pines. What are yours! We'd love to hear!

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Monday, June 5, 2023

|

Conifer Cousins: Ginkgo biloba

By Sara Malone

November 30, 2019

Take a deep dive into a biological cousin of the conifers: the Maidenhair Tree.

Ginkgo are not strictly conifers, but the American Conifer Society includes them

under its umbrella

My introduction to Ginkgo biloba was years ago, as a third year biology student at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, when my path between fall semester classes took me past a large tree with foul-smelling fruit. I was puzzled, because I had passed the tree for two years and never so much as wrinkled my nose. A member of the botany faculty enlightened me. It was a Ginkgo.

Ginkgo are dioecious and wind-pollinated; the tree in question was female, and the only male specimen on campus was far enough away that the wind conditions had to be just right at pollination time, which made success sporadic. Little did I know that that was the last time that I would ask a question about a Ginkgo and receive an unequivocal, short, factual, useful answer!

I embarked on the quest to make order of the world of dwarf Ginkgo cultivars only to learn that it is a world rife with confusion, lack of documentation, little long-term growing experience and enormous reliance on second-or even third-hand observations and interpretations. The usual frenzy on the part of collectors to obtain the latest, rarest, most unusual cultivars has added to the obfuscation, as it provides motivation to keep nomenclature fuzzy and the number of different offerings high. These conditions plague other genera, as collectors of dwarf conifers are only too well aware, but the world of dwarf Ginkgo has some peculiar characteristics which exacerbate the situation.

The History of Ginkgo

Ginkgo are not strictly conifers, and, at this writing, have been classified into their own division, Ginkgophyta, with a single class, order, family, genus and species, of which Ginkgo biloba is the only extant representative. The Ginkgo fossil record dates back some 200 million years. Native to China, they are believed to be extinct in the wild, as today’s populations now appear to have been cultivated. Ginkgo are, however, gymnosperms, and so are more logically lumped with conifers than not, and the American Conifer Society includes them under its umbrella. Ginkgo biloba ‘Mariken’ was even chosen as the American Conifer Society's Collectors Conifer of the Year in 2007.

Even those who have not grown Ginkgo almost certainly recognize them, as they are used ubiquitously as street trees, due to their extensive range, high tolerance of air pollution and their resiliency to wind and snow. In addition, because they are stoic, long-lived, and generally slow growing, they require little maintenance. Their durability is exemplified by the six Ginkgo trees which survived the atomic bomb blast in Hiroshima, a trauma not likely to be approximated in anyone’s garden, black thumbs notwithstanding! The lovely, iconic Ginkgo leaf is a familiar shape in art, craft and jewelry. Ginkgo have long been a favorite choice for bonsai.

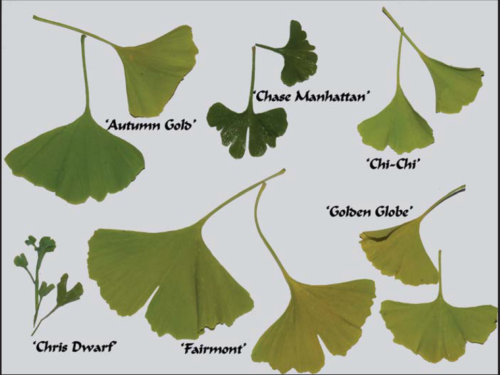

Dwarf cultivars began appearing in the trade in the mid-1980s and there are now somewhere around 30 available in the U.S. As noted, Ginkgo is a monotypic genus. Thus, all cultivars come from one species, limiting the range of variation. Not all are reliably named or documented and many are so new that not much is known about growth rates, mature size and form, or even sex, as Ginkgo generally do not flower or fruit for 20-25 years. Whereas the species generally has a large, irregularly shaped crown, dwarfs come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some are low and branching, others vase-shaped, columnar or pyramidal; some have different shaped or sized leaves. and one even has interesting bark formations.

Cultivation and Propagation

The cultural requirements of Ginkgo cultivars are similar to those of the species, and they generally all share the trait of buttery, golden autumnal color. The vast majority of cultivars originate as witch’s brooms, which Ginkgo produce with reasonable frequency. Two notable exceptions are ‘Gnome’, which originated as a chance seedling at Iaian Hiscock’s Commercial Nursery in Tennessee, and ‘Ross Moore’, which Ross Moore, of Moore’s Natives in North Carolina, found growing in a client’s garden.

The majority of named cultivars (except ‘Green Pagoda’, which, per its catalogue, Stanley & Sons grows from cuttings) are propagated by budding or grafting, with the scion wood of the desired plant grafted onto seedling rootstock of Ginkgo biloba. Lucille Whitman, of Whitman Farms in Salem, Oregon explains: “Much of the scion wood for dwarf Ginkgo cultivars is in short supply, due to the slow growth rate of the plants, their small stature, and their relatively short time in commercial propagation.

However, the good news is that if you can obtain the scion wood, grafting is easy and has a high success rate.” Due to this shortage of scion wood, many of the newest and sexiest cultivars are perpetually sold out and difficult to lay one’s hands on. Crispin Silva, of Crispin’s Creations Nursery in Molalla, Oregon, echoes Lucille’s frustrations about the scarcity of scion wood; he described building up a stock of scion wood as his biggest challenge in propagating Ginkgo cultivars.

Confusion in the World of Ginkgo

It quickly becomes apparent after talking with growers that there have been many new introductions over the last decade or so and very little documentation as to their specific growth patterns, growth rate, stability and variability. Add to that the scarcity of scion wood and the general slow growth rate of the genus, and you have a situation rife with approximation, hyperbole, and misrepresentation, even if much of it is unintentional.

A quick search of Ginkgo cultivars on the GardenWeb Forums, for example, produces pages of questions with incomplete, conflicting or unsatisfactory answers. Many of the cultivars have uncertain antecedents: for example it is not clear if ‘Chris’s Dwarf’ and ‘Munchkin’ are synonyms or not - two distinctly different forms have been observed. A similar situation arises with ‘Chase Manhattan’ and ‘Bon’s Dwarf’, with some claiming that they are the same plant, others that they are distinct and different.

There is also confusion surrounding the four or five offerings which originated at Spring Grove Arboretum in Ohio. One cultivar is named Spring Grove™, which is the trademarked name for a cultivar called ‘Grovbil’ (presumably a purposely un-euphonious shortened combination of Grove and biloba), which was originally termed Spring Grove #9. Thus, at one time or another, three different names have been applied to the same cultivar. ‘Grovbil’ only appears as a secondary name in the listing in the Spring Grove Arboretum catalogue - the plant is universally known as Spring Grove.

Another cultivar was originally named Spring Grove #86, but renamed 'Jehosephat'; another is called ‘Spring Grove Sport’ and another was recently registered as ‘Queen City’, which may or may not be the same as #22, which is referred to on several sites. ‘Queen City’, although a legitimate cultivar, is so new that an internet search comes up completely dry. There may be yet another not in commercial distribution.

Richard Larson, Nursery Manager of the Dawes Arboretum in Newark, Ohio and the North American Registrar for all conifer genera (once again, Ginkgo are included) expresses his frustration with the situation: “Registration is relatively easy and it’s free, but a lot of people don’t want to register plants, so we have Ginkgo coming out [which] were never registered. That means that there is a lot of anecdotal evidence about a number of dwarf cultivars, but no recorded information.”

He also notes that like certain other conifer genera, such as Taxus, Ginkgo are strongly plagiotropic, so that scion wood taken from different parts of the stock plant produces different growth patterns in the grafted product. This makes for differing growth patterns within one cultivar, raising questions about whether the plants are truly of the same name. Finally, due to lack of funds, the annual ‘checklist’, or perusal of the literature of a particular genus, which is supposed to be done on Ginkgo is not being completed, so that there is no current list of legitimately registered Ginkgo cultivars available, to serve as a guide as to which cultivars are “legit” and which might not be.

The Ginkgo's Battle of the Sexes

Because oddities are sought after by collectors (and consequently valuable), any indication of a different growth pattern is emphasized, although it should be noted that Ginkgo, their cultivar names or descriptions notwithstanding, do not display variable forms to the degree observed in other genera. When asked about weeping forms, for example, Richard notes: “No Ginkgo is going to weep like a cherry.” Similarly, Gary Handy, of Handy Nursery, when describing ‘Robbie’s Twist’, says that despite the fact that it is often described as “contorted”, “It is not a true contorted, like say a filbert or a corkscrew willow.” So, for those of you seeking the unusual, temper your expectations and remember that the dwarf Ginkgo are going to display more subtle modifications of the species habit than you might hope to find.

Another peculiarity of Ginkgo cultivars is that most people prefer male plants, due to the malodorous qualities of Ginkgo fruit, which is botanically not a fruit, but rather the fleshy outer coating of the seed. While some female offerings exist, selected and grown for those who appreciate the taste of the hard inner seed, the vast majority of named cultivars are male, or thought to be male. So, now we are down to one sex of one species, from which to produce cultivars!

In fact, because so much Ginkgo propagation is restricted to cloning male plants, there is thought to be some threat to the biodiversity of the genus. It seems odd that the sex of the plant should matter much with a dwarf, especially one that can take 20 years to bear, where the ‘fruit’ would be far fewer than on an enormous species tree, but “male” has become an important adjective in Ginkgo marketing. Therefore, male plants are promoted.

Muddling through Ginkgo Marketing Talk

Clarity is made more elusive still by the fact that many retailers include boilerplate language in their write ups, such as “flowers and fruit are not ornamentally significant”, which implies that the cultivar in question has fruit and is thus a female, when in fact it is a male cultivar. A quick Google search for any number of cultivars reveals exactly the same language on different retail - and in some cases wholesale - websites, indicating that many vendors simply copy (with or without permission) the descriptions supplied by others. One retailer, when contacted about the accuracy of the descriptions of his Ginkgo offerings admitted that they were written by a third party and he had no idea if they were correct or not!

In addition, most retailers, even the more knowledgeable, specialty nurseries, have a very short (and often very narrow) experience with dwarf Ginkgo cultivars, and so must rely on others to provide specifics about growth rates, habit and other particulars. When someone cannot speak from personal experience, there is far more opportunity for descriptions to get mangled. We have been playing the Ginkgo version of “telephone”, the old game where a phrase or word is repeated down a line of people until what the last person hears bears little resemblance to what the first person said.

Thus, a particular cultivar is described by different vendors as “columnar”, “irregularly branching” and “arching and curving” - surely contradictory! Given the difficulties, what’s a collector to do? Stay tuned for the next issue of the Conifer Quarterly, where we’ll share the results of our interviews with growers, retailers, arboretum professionals, and plantaholics with a list for those who want the most reliable selections…and further, choices for those who want to push the envelope!

Thumbnail photograph by Jerry Wang. Catalogue photographs by Harold Greer.