|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Web Editor

October 11, 2019

Learn about variegated ginkgos with Mr Maple co-founder, Tim Nichols.

Ginkgo biloba ‘Snow Cloud’ during summer

Propagation and Cultivation of Ginkgos

First, I don’t think I can talk about cultivation of ginkgo without talking about giving them lime. Ginkgos prefer a more alkaline growing condition. You will notice a big difference in the health and growth of a tree with a more alkaline pH vs. a more acidic pH.

Variegated ginkgos are sought by collectors for their unique character and interesting variegated foliage. Many can prove difficult to propagate while maintaining the variegation. One common tactic is to prune out “reversions." While this method may be effective from time to time, some non-variegated branches may appear variegated the following year, while variegated branching may show no variegation the following year. It is still important, as with most variegated plants, to produce from plants that display the most stable variegation.

Another method is to give variegated ginkgos more sun. Often variegated ginkgos lose variegation more quickly in shadier conditions than in sunnier growing conditions. At our nursery, we have played around with the idea of rooting variegated selections, but these same problems appear to affect both grafted selections and rooted selections.

Ginkgo biloba ‘Jagged Jester’

Ginkgo Cultivars: 'Jagged Jester'

While ‘Variegata’ may be the most common of the striped variegated selections, many other cultivars exist, such as ‘California Sunset’, ‘Jerry Verkade’, ‘Joe’s Great Ray’, ‘Majestic Butterfly’, ‘Sunstream’ and ‘White Lightning’, to name only a few. Some of these may have a white striping variegation, while others may be more a creamy yellow. All of these striped, variegated selections can revert and do so frequently.

Ginkgo biloba 'Jagged Jester' is one of the most unique ginkgos I have seen. While this variegated plant still can revert, it reverts to one of my favorites, ‘Jagged Jade’, which has thick attractive foliage. Some believe this thicker leaf to be an indicator of a polyploid ginkgo, but I don’t know anyone who has tested this in a lab.

'Jagged Jester' was found as a variegated sport on the cultivar 'Jagged Jade' by one of our friends, Crispin Silva in Moalla, Oregon. We would expect 'Jagged Jester' to grow to 5 or 6 feet in 15 years. Fall color is a bright neon yellow.

Ginkgo biloba ‘Pevé Maribo’ showing color

Ginkgo Cultivars: ‘Pevé Maribo’

‘Pevé Maribo’ is a variegated sport that was found on the ever popular dwarf ‘Mariken’ by Piet Vergeldt in the Netherlands. The creamy yellow variegation gives this dwarf a little extra added flare and makes it unique. While this variegation is just as unstable as other variegated ginkgos, it reverts to ‘Mariken’, a 2010 ACS Collectors’ Conifer of the year. This isn’t a very risky plant, as either way it will be beautiful, dense and compact. ‘Pevé Maribo’ may reach 4 feet x 5 feet in 10 years.

Ginkgo biloba ‘Beijing Gold’ with Summer Variegated Flush

Ginkgo Cultivars: ‘Beijing Gold’

‘Beijing Gold’ is a uniquely variegated ginkgo that doesn’t revert. In the spring, older plants may leaf out completely yellow. As the spring progresses, chlorophyll pushes green into the leaf while the yellow begins to leave. By late spring to early summer, the foliage has turned to a solid green. New growth during the summer will often display white striped variegation.

While the older growth does not show this variegation, this ginkgo does not revert. Fall color, like most ginkgos, is a bright, neon-yellow. While the name makes one think this tree originated in China, the farthest I can trace this tree back is to the Netherlands in the late 1990’s to early 2000’s. ‘Beijing Gold’ may reach 8 to 10 feet in 15 years.

Ginkgo biloba ‘Snow Cloud’

Ginkgo Cultivars: ‘Snow Cloud’

‘Snow Cloud’ is perhaps my favorite ginkgo, primarily because it doesn’t revert and displays a snow-like frosty variegation. Originally brought over from Japan by our good friend Barry Yinger of Asiatica Nursery, the original name on this ginkgo was ‘Frosty’.

Years later, as soon as we tracked down a ‘Frosty’ from one of Barry’s customers, we started grafting it and getting it into production. ‘Snow Cloud’ hit the market, which happens to be the same tree. While ‘Frosty’ may have been the original name, ‘Snow Cloud’ is now the more accepted name in the nursery trade.

In hot climates, the white frosted variegation will fade more, but it always puts on a great spring display of variegation. Give 'Snow Cloud' morning sun and protection from the hot afternoon sun for best variegation. Fall color is a bright, golden yellow. We expect 'Snow Cloud' to reach 6 to 8 feet in 10 years.

Text and photographs by Tim Nichols.

Tim Nichols is co-founder of MrMaple; he and his brother, Matt, own a nursery near Asheville, NC with over 1,000 cultivars of Japanese maples alone. Click here to visit their website.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Dana Behar

September 28, 2019

Learn about the prized ornamental tree of the Japanese umbrella pine.

Conifer close up of a Japanese umbrella pine in the garden

About 25 years ago, a young graduate of the Yale School of Forestry, Lorens Fasano, had the opportunity to buy 550 saplings at a local nursery that was going out of business. Knowing the rarity of the species, Lorens purchased all of the trees, which he carefully planted nearby, on the 82-acre property of his parents, in rural New Jersey.

Some 25 years later, Lorens has what is believed to be the largest collection of mature specimens of this species in North America. The species in question is Sciadopitys verticillata (Japanese umbrella pine), kôyomaki in Japanese. It is not actually a pine, but is, in fact, one of the rarest and most unusual conifers in the world.

It is also one of the earliest conifers, dating back to the Triassic period. S. verticillata lived before the existence of dinosaurs. Originally comprising a wide variety of species with a habitat spreading across continents, Japanese umbrella pines became virtually extinct. The geographic range of the trees has at present been reduced to just two isolated areas in Japan, with the diversity becoming limited to a single species.

Conifer Anatomy of the Japanese umbrella pine

Japanese umbrella pine derives its common name from the whorls of needles that grow at the end of its branches and that mimic the spokes of an umbrella. The heavily needled branches cover the tree in a cloak of green. The needles are of the richest shade of green, soft, round, and waxy to the point that they look almost like plastic.

The needles grow 2-5 inches in length in whorls of 20-30 and contrast elegantly with the bark, which is thick, soft, orange-brown, and stringy. The needles are actually photosynthetic flattened stems, called cladodes. Japanese umbrella pines are extremely slow-growing, typically taking up to 100 years to reach a full height of 25-40 feet.

Now considered a living fossil, it is a genetic orphan, the only remaining member of the family Sciadopityaceae, of the genus Sciadopitys. The tree is found in Japan on the Nara Peninsula of Shikoku Island and in the mountains northeast of Nagoya on Honshu Island. Kôyamaki is one of the five trees of Kiso that are treated as sacred in Japan.

Lorens Fasano with one of his umbrella pines from his conifer garden collection

A Valued Garden Conifer

Historically, its spicy-scented, water-resistant wood was highly valued for making boats, and its bark, in the form of oakum, for caulking. Now listed as vulnerable, it is too rare to be used as anything other than a highly prized ornamental and is found in many of the leading gardens of the world.

Fast forward to 2019. Lorens Fasano now has 340 mature Japanese umbrella pines on the property his mother owns. Lorens is trying to find new homes for these trees, as the 82-acre property needs to be sold. Although he had not previously been active in marketing the umbrella pines, his trees have been sought after and can be found at Brooklyn Botanical Garden and Hudson Yards in New York, NY, Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, NY, and Carnegie Mellon University, in Pittsburgh, PA.

Lorens has lovingly cared for these trees for over 25 years and is determined to find good homes for the rest. The trees are being offered to colleges and universities, botanical gardens, Japanese gardens, and landscape architects. Those interested in learning more about these trees may contact Dana at: [email protected] or visit www.umbrellapines.com.

Notes from Ron Elardo and Dave Olszyk

Here are some interesting facts about Sciadopitys verticillata (Japanese umbrella pine):

The botanical name for the tree comes from ancient Greek: σκιά (skiá), English translation: “shadow”; and pitys, (Πίτυς), English translation: “pine”. The epithet, verticillata, means “with whorls”. This suggests that the “shadow pine” is naturally an understory plant.

Its Japanese name is コウヤマキ(kôyamaki). An image of the tree is on the crest of Prince Hisahito Akishino, currently the third in line to the Chrysanthemum Throne.

Japanese umbrella pine dates from 230 million years ago. According to fossil records, its range included the Baltic Coast of Europe. Chemical and fluorescent analyses of its resin link it to Baltic amber, created from the sap of the tree being fossilized and then washing up onto the coasts of Baltic Coast countries, such as Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Russia.

Amber “stones” were traded by both the Romans and, then, later, by the Vikings. Many times amber (called in German Bernstein) has inclusions with insects and plants preserved in it. Such stones are highly prized.

Near St. Petersburg, Russia, there once was an Amber Room in the Catherine Palace of Tsarskoye Selo. It was dismantled and stolen by the Army Group North of Nazi Germany in the siege of St. Petersburg. After World War II, Russian craftsmen spent decades reconstructing the Amber Room with donations from The Federal Republic of Germany. In 2003, the Amber Room was rededicated in the Catherine Palace.

The original Amber Room was considered an “Eighth Wonder of the World” and had been given as a gift to Russian Tsar Peter the Great by King Friedrich I of Prussia in 1716.

German researchers believe they have found the stolen Amber Room in the Berlin City Palace (Das Stadtschloss), which itself has been reconstructed and rededicated on the Museum Island (die Museuminsel), in central Berlin.

Photographs by Dana Behar.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

February 5, 2016

It’s easier than you might imagine, saves money, and makes the hobby all the more gratifying! If you are like me, you started out with perennials, constantly having to divide, deadhead and feel like you should be trying out for a body-building competition after wrestling with all the overgrown plants and sometimes weeds. Not to mention avoiding inviting your friends in August since your perennial gardens are beginning to look tired.I got started in conifers after attending a seminar presented by Gary Whittenbaugh in Grand Forks, ND. I heard this during that seminar: why should someone grow conifers? No deadheading No spring or fall clean up Year-around beauty — I was sold! Once Gary heard that my passion lies with rooting plants or planting up seeds, he fed my obsession with many cuttings, not to mention the numerous hours we spend talking about conifers, which plants do well in my northern frigid temperatures and what conifers do well from cuttings, etc. I feel so fortunate to have such a wonderful friend and mentor. Now, have you spent all your cash with your spring purchases and need more conifers? Did you know there are some conifers that are easy to multiply by taking cuttings and allowing them to root? Let’s venture into the world of rooting conifer cuttings.

Conifers that readily root by cuttings:

Abies - koreana and balsamea cultivars

Cedrus / Chamaecyparis

Cryptomeria / Juniperus

Picea - some will root fairly easily.

Podocarpus / Taxus / Tsuga / Thuja

Cuttings should be taken from healthy plants as these will root better than those from sick or stressed plants.

When and how to take cuttings

Plants have an internal chemistry that changes with the seasons. Therefore, taking the cuttings at the correct time of year is most conducive to rooting that particular plant. As a general rule, conifer cuttings root best when taken after the first few hard frosts of fall when the plants are in dormancy. The dormancy factor is satisfied by cold temperature (35 degrees Fahrenheit down into freezing temperatures) for at least 6 weeks. I’ve had the highest successful percentage rooting when the conifer cuttings were taken from December through February.

When taking cuttings I like to use this season’s growth as it is easier and faster to root than old wood in most cases. Basically you are taking a tip cutting two-to-three inches in length. It is entirely possible to use the old wood or past season’s growth but the amount of time it takes to produce roots with these old wood cuttings is a bit longer.

Preparing the rooting chamber

A greenhouse is not necessary for successful propagation. I use large clear/opaque totes as my rooting chamber. Maintaining high humidity around the cutting is critical and I find totes work perfectly and are inexpensive. I fill the tote with a soil-less medium of 1:1 peat moss and perlite to a depth of about 3 to 4 inches. If you choose to use something other than peat moss and perlite, make certain whatever medium you are using is sterilized. You will be leaving these conifer cuttings in this rooting chamber for a long time (ideally 12 months) and you do not want to introduce any pathogens which will result in mold, eventually killing your cuttings.

Once you have your soil-less medium in the rooting chamber, you need to add enough water to the mix to make it damp, not soggy wet. Too much water and your cuttings will rot, too little water and your cuttings will dry out. I think one of the biggest keys to my success is that I use rainwater or pond water instead of tap water.

Preparing the cutting

I take my cutting, make a cut below a leaf and remove leaves from the bottom third of the cutting if possible (any foliage that would be in contact with the surface of the compost could rot) then at the end of the cutting stem snip the end at a very severe angle exposing as much of the cambium layer as possible.I will then dip my entire cutting leaves and prepared stems into a rooting hormone and place them into a premade hole in the soil-less medium in my tote. I always take a pencil and create a hole in the pre-moistened soil-less medium, as I do not want to displace any of the rooting hormone. If you are into labeling your plants in your gardens don’t forget to label your cuttings. Trust me: if you put it off until later you will most likely forget the name.

I have used several different rooting hormones; Clonex, Rootech Cloning Gel, Olivia’s Cloning Rooting Hormone ... However, I have had the most success with Dip n’ Grow and Dyna Gro K-L-N. If I use the gel I cannot dip the entire cutting piece in the rooting hormone. In addition, I never use the powder rooting hormones as I have never had much success with the powders. Be careful with the rooting chemicals. I just dip the cuttings and place them in pre-moistened mix. Do not allow them to sit in the rooting chemicals as it will burn the tissue.

Putting it all together

Now that we have all our cuttings tucked nicely into our rooting chamber, with the lid fit tightly in place, we need bottom heat. The temperature of your medium is very important for callusing and root stimulation. I use heat mats and I also have a few waterbed heaters (Not sure if the electricians approve of waterbed heaters but they are inexpensive). Place your rooting chamber on these mats and heat to 70-72°F. Remember, we want warm feet and cool heads. I will leave my rooting chamber on these mats until March or April when the temperatures start increasing. I do have the rooting chamber in an eastern sun exposure in my house or in my greenhouse.I peek into the containers to ensure things are looking good. I watch for mold and dry soil. I usually have to mist the plants/soil’s surface with fungicide laced water about once every other week and more often if I see any signs of mold or the soil is too dry. When I mist, I mist with rain water or pond water instead of tap water.

Aftercare

Once I take the rooting chamber off of the heat mats I move the totes under my benches in the greenhouse. For the past few years I have been stacking all my totes outside on the north side of the greenhouse or down in my basement and mostly forget about them, only peeking periodically to ensure they are not drying out, until November or December when things in my life slow down. That is when I will pot them up. I am finding the longer I keep them in the totes, the better root systems they have. Once they are off the heat mats it is best to keep them in a shaded area and out of direct sunlight.

Some of the plants take a bit longer to root and definitely need a full year or two to root. Once you begin experimenting with cuttings you will be able to tell. You will see with these slow rooters, that they will have a large bulbous bump and no roots or a slight start of a white thick root. When you see this, you will know this specific conifer needs more rooting time.

Please note: before re-using these totes (rooting chambers), wash them out very well with bleach water. This is imperative. I lost an entire batch of cuttings from using my totes over and over without cleaning them up with bleach.

I usually keep up-potting my conifer cuttings until I get them potted into gallon containers. At this point I will plant them out in my gardens.Growing conifers from cuttings is a rewarding experience and seeing the fruits of your labor come to life makes this hobby all the more gratifying. You can also expand your varieties by trading your newly rooted plants with fellow conifer enthusiasts.

The article was written by Tangula Unruh. Reprinted from The Coniferite

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Learn how to provide the best foundation for your conifer planting and growth.

The conifer, Norway Spruce (Picea abies ‘Cupressina’) in clay-loam

Siting plants on an inclined plane or irregular rolling slope adds interest to a flat surface and provides the opportunity to stage dwarf plants toward the foreground. Large or intermediate conifers can be used to block unwanted sightlines. Color, texture, form, seasonal changes, bark, and coning attributes provide great options.

Whatever landscape situation exists, there is a superlative conifer available for that site. Basic knowledge of conifers and of the site is required to make wise plant choices.

Considering Soil Foundation Types for Conifers

Before planting conifers, you must be able to answer this critical question: What is the drainage and percolation of the site? Most conifers thrive in well-drained sandy, clay loam in full sun. Not all projects have ideal conditions, but good drainage is essential to guarantee the success of most plantings.

Test your soil percolation by digging a hole 2’ deep with a post hole digger. Fill the hole with water, let it drain and fill again. If the hole does not drain in two hours after the second filling, the soil is limited for conifers. In heavy clay, raise at least half the root ball out of the clay layer and surround the protruding half with good topsoil.

Another solution is to remove narrow channels of clay leading away from the plant, like spokes of a wheel. Replace that soil with sand or pea gravel so that water and rootlets have an easy path. Water must drain away easily, or the roots will rot due to lack of oxygen.

The conifer, Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora ‘Pendula’) in clay soil

Matching Conifers with Soil Types

If your soil is heavy and wet and can’t be amended, there are some conifers which are naturally predisposed to such conditions. Choose Larix (larch), Taxodium (bald cypress), Metasequoia (dawn redwood), or Thuja (arborvitae). Taxodium distichum is one of the most versatile conifers because it can thrive in standing water or on a rocky ridge. It is the most adaptable to heavy clay soils.

Taxus (yew), Pinus (pine), Picea (spruce) and Abies (fir) demand good drainage and will die with too much water in the soil. Provide your trees with good soil, amendments, and sufficient water. Extra watering is needed during drought periods and until the ground freezes.

Soil Ammendments for Conifers

Mulch is a positive thing to maintain soil moisture, but it should not be placed too close to the trunk. Chunk bark or coarse wood chips can be beneficial for firs (which prefer an eastern exposure). Pine needles, coarse pine fines or 2” wood chips work well for other conifers. Use a light application of compost, peat moss or worm castings and sulfur in reasonable doses for these acid-loving plants.

Photographs by Susan Eyre.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2014 issue of Conifer Quarterly. Join the American Conifer Society to access our extensive library of conifer-related articles and connect to a nationwide group of plant lovers! Become a member for only $40 a year and get discounts with our growing list of participating nurseries in our Nursery Discount Program.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Container Gardening with Conifers

By Sharon Elkan

September 27, 2019

Get container gardening ideas on how to make the most of plants like conifers and vegetables.

Boxed-up conifers in containers on a deck

My passion for landscaping began in the early 1970’s when my husband, Michael, and I moved from Philadelphia to Oregon. We bought a home close to Silver Falls State Park. I installed a huge rock garden, which included: Sedum spp. (sedums), Sequoia sempervirens (coast redwood), and many small perennials. I did not know much about miniature and dwarf conifers. Looking back to that time, I now realize that many genera of conifers would have been perfect for the sunny exposure the property presented!

Then, 35 years ago, Michael and I purchased property on a beach about 25 miles north of Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. While our house was being built, I quickly learned which plants could tolerate a salty, windy environment. Within one year, I had planted several species of the family Arecaceae (palms), along with Cycas spp. (cycads), Polypodiophyta spp. (ferns), Agave spp. (agaves), Philodendron spp. (philodendrons), and many more species of plants. I worked on that tropical garden for 24 years.

Starting on a Boxed Conifer Journey

I moved back to Silverton, OR, about four years ago, after I lost Michael to cancer. My new living space is a 2nd-floor apartment with a 10-square foot deck. I wondered how I might landscape that space. “Plant in boxes”, was my answer.

I commissioned a local carpenter to build containers, using Trex decking material. Voilà! I had a new blank garden canvas. Next, I needed a medium for the conifers I had begun to acquire. I created a soil mixture out of compost, pumice, and fir bark chunks. It drains very quickly, which I knew was important. After all, plants in container gardens, like conifers and vegetables, do not like to sit in water.

A close up of conifers in garden containers

Selecting Conifer Genera for Container Gardening

Two boxes are 2 feet x 3 feet by 1-foot high. A third container measures 3 feet by 16 inches and is also 1-foot high. I have also added many ceramic pots to accommodate even more plants. I planted 10 different conifer genera.

Chamaecyparis obtusa (hinoki cypress) ‘Greenstone’, ‘Gemstone’, ‘Chirimen’, and ‘Nana Lutea’ thrive and grow in the boxes. To the shades of green of the first three cultivars, ‘Nana Lutea’ asserts a standout yellow.

There are also three cultivars of Chamaecyparis lawsoniana (Lawson cypress) in the boxes: ‘Ellwood’s Nymph’, ‘Wissel’s Saguaro’, and ‘Treasure Island’. These three flip-flop between greens and golds and are slowgrowers. 'Ellwood’s Nymph’ is a mini, and ‘Wissel’s Saguaro’ reminds me of the cactus after which it was named.

Conifer cultivars for container gardening

Cultivars of Chamaecyparis pisifera (sawara cypress) add to the texture of the landscape. ‘Curly Tops’ and ‘Tsukumo’ pop. The former is a steely blue. ‘Tsukumo’ offers a bun-shape. Two Thuja occidentalis(eastern arborvitae), ‘Amber Glow’ and ‘Franky Boy’ add different dimensions. ‘Amber Glow’ does just that: it “glows”. ‘Franky Boy’ has cute, stringy, lemonyellow foliage.

I used one Cryptomeria japonica ‘Tenzan’ (Tenzan Japanese cedar). It has a dense, mounding, shape. Abies koreana ‘Kohouts Icebreaker’ (Kohouts Icebreaker Korean fir) is silvery. A. nordmanniana ‘Jakobsen’ (Jakobsen Nordmann fir) draws the eye to its dense, pyramidal form. I used two more firs, A. concolor ‘Tubby’ (Tubby white fir) for its puff of greenish-blue, and A. borisiiregis ‘J.K. Greece’ (J.K. Greece King Boris’ fir) for its spreading habit.

Conifer Boxing Up with Pines

What conifer garden would be complete without pines? Pinus mugo ‘Real Little’ (Real Little mountain pine) is sweet and compact. ‘Little Gold Star’ shines like the sun. ‘Jakobsen’ looks like an in-ground bonsai. Lastly, Pinus parviflora ‘Tanima no yuki’ (Snow in the Valley Japanese white pine) is perfect for a “boxed” landscape.

Picea pungens ‘Blue Pearl’, P. pungens ‘Pali’, and P. mariana ‘Blue Planet’ show off the hues that we all love about blue spruces. Add to that appeal the slow growth of all three cultivars, and you have some of the best conifers for small spaces. Picea orientalis ‘Tom Thumb Gold’ (Tom Thumb Gold Caucasian spruce) also has a habit conducive to container gardening, with its striking, gold fingers and tight foliage. Cedars are always a hit in any garden, either in a full-sized landscape or in a garden like mine.

I used two cedars in my containers: Cedrus libani ‘Green Prince’ and C. libani ‘Hedgehog’. Both choices of Lebanon cedar have two important habits for the small garden: they are both slow growers and centerpiece plants. Finally, I chose Juniperus communis ‘Gold Cone’ (Gold Cone common juniper), which works both actually and figuratively as an exclamation point in the garden.

A container gardening deck for conifers

A Conifer Deck to Pine For

My greatest inspiration for creating a small conifer container landscape was The Oregon Garden, here in Silverton. ACS member Doug Wilson, who manages the conifer garden and has so much knowledge and artistic talent, has been a huge influence on me.

Each year this magical Oregon Garden gets more beautiful. My deck gives me enormous pleasure. The landscape of colors, textures, and shapes, which I enjoy every season of the year, is the best gift I have ever given to myself. It is my hope that my inspiration can become yours for your conifer, vegetable, or flower garden, as well.

We do not all have large spaces for a conifer garden. However, with the right research and the right conifers, any sized conifer garden can work!

Photographs by Sharon Elkan.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Web Editor

July 26, 2020

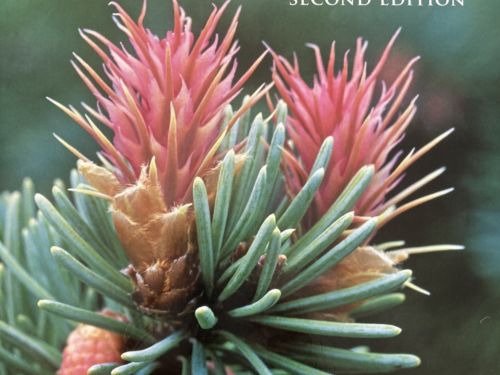

Adrian and Richard Bloom have updated and enhanced their 2002 classic

It is only fitting that I write a review of the new, second, edition of Adrian Bloom’s book, Gardening with Conifers, (Firefly Publishing, 2017) since it was the first edition, published in 2002, that introduced me to conifers (How I fell in Love with Conifers) and began for me what varies from a hobby to an obsession, depending on one’s viewpoint! While his prose is compelling, it was the photographs, by Adrian and his son Richard, that captivated me: the depictions of the incredible variety of colors, shapes, sizes and textures in the conifer collection that populates his 50 year old, 17-acre Foggy Bottom Garden in Bressingham, Norfolk, England. The second edition has even more photos, an updated directory of desirable garden conifers, and, my favorite part, a section on the Foggy Bottom garden at 50, complete with ‘then’ and ‘now’ photographs that clearly depict the successes (and sometimes mistakes!) of beginning with small specimens and seeing them grow to maturity.

For the gardener and plant-lover, the book provides inspiration for using conifers with other plants, sometimes woody specimens, sometimes perennials, and even bulbs and ornamental grasses. Adrian discusses cultural requirements, placement, growth rates, pruning, etc—all that one needs to understand how to be successful at adding conifers to the garden population. Particularly useful for those with small gardens is the section on conifers in containers. For the serious conifer-collector, the Directory of Some of the Best Conifers is revised and expanded, from 84 pages to 103, and now includes cultivars and species that had not been created or identified when he published the first edition.

Watch Adrian discuss conifer pruning

The new edition also includes a chapter on the development and planting of a garden in Friesland in northern Germany, called Mauergarten, which translates to ‘Walled Garden’. This is both a charming story of friendship and collaboration and an informative and interesting history of the building of a garden, from conception to fruition. While this project is beyond the scope (and possibly the imagination!) of many of us, it is still instructive and we can relate many of Adrian’s challenges to those that we face in our own garden design.

While the new edition is over 15% longer than the first one, it contains more than 15% more information because, without seeming to crowd either the text or the photos, there is more of both crammed onto each page. The first edition’s directory claims to include ‘over 600 conifers’ and I did not stop to count the list in the 2nd edition, but it is clearly much longer!

Finally, as an ACS member, it is pleasing to know that on some level, Adrian and I are equals. We are both individual members of the Society. That is the ONLY level on which we are equals, but it’s fun to dream! It’s also fun to see that in the credits, first shout-out goes to ACS member Dennis Groh, who helped with the project all along the way. I would like to give a shout-out to both Adrian and Richard, for updating what was already a classic and making it even more informative, lush and inspiring. I’m inspired now, so I am going to close, and go out into the garden! Buy this wonderful book and get inspired, too.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Tom Cox

March 15, 2020

Curious about rare and unusual conifers? Discover the world's rarest evergreens from the US and internationally.

The rare conifer, David's keteleeria (Keteleeria davidiana), an evergreen from Taiwan and Southeast China

When one thinks of ex situ (outside its natural habitat) collections of rare and endangered conifers, institutions such as Bedgebury Pinetum, Kew Gardens, Arnold Arboretum, and Missouri Botanical Garden come to mind. Each of these do in fact have impressive collections with Bedgebury likely being at the top. One of the last regions one might consider looking would be the Southeast U.S – a region generally viewed as unfriendly to conifers.

When the Cox Arboretum was started 26 years ago, no thought was given to conifers – period. As the years went by here, we started acquiring more and more. Soon a love affair began with conifers; the majority being cultivated varieties (cultivars). Then at some point along the growth curve, I became more and more fascinated with straight species, which I find every bit as beautiful as any cultivar.

In fact, today my major focus is on species conifers. Of primary interest was evaluation of species that had never been trialed in the southeast or rarely seen in any botanical garden or arboretum. By way of example, we are currently trialing 21 different Abies (firs) on their own roots and are collecting data on these firs from various regions of the world to determine what might adapt here.

A Wide Array of Conifers and Evergreen Trees

Today, we are widely considered to house one of the largest (most complete) conifer species collections in the U.S. There are so many species that would not survive further north or further south than Zone 7b. For many species, such as those native to Southeast Asia, our climate is even more hospitable than Northern California, Oregon or Washington.

Several factors contribute to this with the first being that we receive, on average, 55 inches of rain per year, and the rain is distributed throughout each month. The US average is 37. The second factor is no temperature extremes on either side of the dial. While it can get hot, more conifers than not actually benefit from summer heat and humidity.

Other factors in our favor include a long hardening-off period, which enables our plants to shut down early enough to be prepared for winter. Remember, it’s not how cold it gets, but how it gets cold. We have a long growing season, and even our coldest days are short lived. Some plants are able to withstand some cold as long as that cold is not long in duration.

The rare evergreen, Lumholtz's pine (Pinus lumholtzii), a conifer from Mexico

These facts are seldom mentioned (if at all) outside of academia, since most conifer discussion in the U.S. is focused on what does well in regions considered conifer friendly, e.g., Michigan, New York, Oregon, etc. For every plant we cannot grow well, such as interior conifers from the Northwest, there are dozens that will prosper here.

Until now, they have never been tried, there is no literature, and many are next to impossible to locate. Happily, institutions such as the J. C. Raulston Arboretum and Atlanta Botanical Garden, along with pioneering research by Dr. John Ruter, are helping to change this. I also am aware that ACS members Neil Fusillo and Scott Antrim are creating an impressive inventory of species conifers.

A natural off-shoot of a large species collection is that a number of these are rare and endangered. Approximately eight years ago, we were contacted by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) and asked to participate in a survey of worldwide gardens holding large ex situ collections of threatened conifers. The overall goal is to support the Global Trees Campaign (GTC), a joint initiative between BGCI and Fauna and Flora International to safeguard threatened tree species.

A Global Survey of Endangered Conifers and Evergreen Trees

A global reassessment of the conservation statuses of the world’s conifers was undertaken, and up-to-date assessments were published in the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List of Threatened Species in July 2013. This work was coordinated by conifer expert Aljos Fargon and jointly undertaken with staff at the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. The global reassessment highlighted that 34% of conifers are globally threatened with extinction. Yes, extinction.

Maintaining ex situ collections is important as it provides a back-up if wild populations are lost due to natural disasters, vandalism, invasive pests or diseases, or human disturbance. Think of it like a zoo. They are also important for breeding purposes, as in the case of our native eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) which is being decimated by the wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae). Active breeding work is presently going on using Asian species which are immune, in an effort to develop a disease resistant tree.

The exotic conifer, Fujian cypress (Chamaecyparis hodginsii) from China and Vietnam

The Big Picture: Depending on the taxonomist, there are approximately 615 conifer species recognized globally. As mentioned above, in 2013, 34% (or 211 species) were listed as threatened with extinction – an increase of 4% since the last complete assessment in 1998. Of these 615 species, many are native to more tropical regions of the world such as New Caledonia, Fiji and New Guinea. These obviously are not suitable for planting outdoors in Zone 7b.

With the exception of several Araucaria, Agathis, and Nageia species, which are grown as houseplants, we do not collect tropical conifers at Cox Arboretum, and they are not counted in our inventory of endangered plants. In our most recent inventory, we verified 76 temperate species on the property that are listed as threatened. Likely, few institutions in the U.S. have this many threatened species growing in one place.

Endangered Conifers: The Florida Nutmeg-Yew

Native here in the Southeast is one of the rarest conifers in the world, Torreya taxifolia. For thousands of years, it was a large evergreen tree endemic to the ravine forests along the Apalachicola River which snakes through the Florida panhandle. Somewhere around 1950, the tree suffered a catastrophic decline as all reproductive-aged trees died. In the decades to follow, the species has not recovered. What remains is a population at approximately 0.3% of its original size, in a manner reminiscent of American chestnut following chestnut blight.

While the pathogen (Fusarium torrayae) has been identified by researchers at the University of Florida, no cure has yet been developed. Propagation efforts spearheaded by the Atlanta Botanical Garden have resulted in a significant quantity of clones being distributed to a number of botanical institutions. We are proud to have received three trees that are growing on.

Another rare tropical evergreen, Yew Podocarpus (Podocarpus macrophyllus) from China

In addition to the aforementioned Torreya taxifolia, I will discuss two more. Pseudotaxus chienii (Whiteberry yew), is the only species of this genus. It is endemic to southern China and is listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Only 10 populations remain in China. Over the past three generations (90 years) the populations have been reduced by more than 30% due to exploitation and habitat loss.

Adding to its decline are factors such as naturally occurring in low density and poor regeneration ability. While we have but one plant, it has grown well here for over 10 years and is well adapted. The fact that we only have one plant is somewhat problematic as it limits our genetic diversity or gene pool.

The third highlight plant is Cupressus chengiana var. jiangensis, which is only known from a single tree. Reportedly, there are fewer than 50 mature individuals of this variety that have been recorded.

The conifer, Cathay silver fir (Cathaya argyrophylla) from China, showing the abaxial side of the leaf

Other rare and endangered conifers of note growing at the Arboretum include:

Abies nordmanniana ssp. equi-trojani

Glyptostrobus pensilis

Juniperus bermudiana

Nothotsuga longibracteata

Picea martinezii

Picea neoveitchii

Pinus armandii var. mastersiana

Torreya jackii

Torreya fargesii var. yunnanensis

In conclusion, there are many conifer species that are of interest that have proved to be adaptable here in Zone 7b. Visitors here continue to remark about the beauty of many of these and how unusual they are. As an added bonus, we are providing a home for some of the rarest conifers on earth.

Photographs by Tom Cox.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

A Man Named Pearl

By Hive By Flannel

October 2, 2017

Pearl Fryar of Bishopville, SC, the son of a sharecropper and former mill worker, is an abstract artist whose medium is topiary. He was the subject of a 78 minute documentary produced in 2006 by Susie Films called A Man Named Pearl. The two-minute trailer included here is on the producer's site. The whole video can be viewed on Netflix.

To read more about Pearl, click here.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

By Frank Goodhart

August 30, 2019

Read about one of the native hemlock and dwarf conifer of the US. This is part 1 of the Canadian Hemlock series. Click here to read part 2 and part 3.

Tsuga canadensis ‘Sargentii’ (Sargent’s weeping hemlock)

Canadian hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) were the first dwarf conifers I ever bought and collected. It was about 1980, when I first visited the (now closed) Watnong Nursery in Morris Plains, NJ. The owners were Don and Hazel Smith, who established a nursery in their backyard after retiring. They specialized in rock garden plants, dwarf conifers, and other plants, which were rare and of interest to the keen collector. The Smiths were enthusiastic, kind, and empathetic to all who visited their nursery. Indeed, among their many contributions, was the education of their clients via long and patient discussions.

Sometimes the Smiths stocked 10-15 Canadian hemlock cultivars at one time. In those days, these plants did not have much availability anywhere in the United States. On the East Coast, many were acquired from other hobbyists and collectors, including ACS charter members Bob Fincham in Pennsylvania, Eddie Rezek and Joel Spingarn in New York, and Tom Dilatush in New Jersey. The Verkade and Vermuelen nurseries, both in New Jersey, also stocked Canadian hemlock cultivars. Don Smith propagated some cultivars by rooting them in a Nearing Frame.

A Versatile Landscape Conifer

Canadian hemlock is one of the four hemlock native to the United States. Its growth range extends from Quebec and Nova Scotia into the New England states, New Jersey, Pennsylvania (where it is the state tree), westward to disjunctive populations in Ohio, Illinois, northeastern Minnesota, the Appalachian Mountains, and as far south as Georgia. As a landscape plant, Canadian hemlock grows well in both sun and shade. Its natural habitat begins at 1,000-feet elevation and extends up to several thousand feet above sea level in mountainous areas. One may often observe them in cool, shady ravines.

The other native hemlock are: Tsuga caroliniana (Carolina hemlock), T. heterophylla (western hemlock), and T. mertensiana (mountain hemlock). Carolina hemlock grows in the Blue Ridge Mountains from Virginia to Georgia. The mountain hemlock grows at higher elevations on the West Coast from California to Alaska. Its distribution is similar to that of the western hemlock.

There are four species of Asian hemlock: Tsuga chinensis (Chinese hemlock), T. diversifolia (northern Japanese hemlock), T. dumosa (Himalayan hemlock), and T. sieboldii (southern Japanese hemlock). Cultivars of these species are uncommon except for T. diversifolia (northern Japanese hemlock), of which there are a few. T. diversifolia is native to the Japanese islands of Honshū, Kyūshū, and Shikoku. In Europe and North America, T. diversifolia is sometimes employed as a tree for the garden. It has been in cultivation since 1861.

Tsuga canadensis ‘Cole’ (Cole's prostrate Canadian hemlock)

The Conifer with a Prized Exterior

The wood of the Canadian hemlock has not been useful for general construction purposes because of its softness and lack of durability. It has, however, been used as a source of pulp in the paper industry and to make crates. In the past, it was mercilessly harvested only for its bark, which has a very high tannin content of about 8%–10%. Large forests were decimated for the sole purpose of harvesting only the bark. Extracted, hemlock vegetable tannins were used to cure and color leather. The stripped logs were left behind to rot.

Virgin forests of Canadian hemlock are non-existent today. The trees were an important part of forest ecology, making up as much as 33% of the forests in some areas of the Northeast. However, there are some very large trees remaining in several states. The current data may be found on the Eastern Native Tree Society (ENTS) website. Recently, a tree in the Great Smoky National Park (NC and TN) was 173-feet tall (52.8 meters), although this tree is now dead from hemlock woolly adelgid. Diameters of existing, isolated hemlock range from 2 feet 6 inches to 5 feet 11 inches (0.75–1.8 meters) and are about 150-feet tall (45.5 meters).

Conifer Collector's Favorite

T. canadenisis is perhaps the most graceful of our native eastern North America conifers with its gentle, weeping branches and informal, conical shape. It has been used effectively as a hedging tree, since it can be pruned regularly to increase branch density, while controlling its overall height. As a specimen tree, it can grow to a height of 70 feet (20 m) and a width of 25 to 35 feet (7.5 - 10 m). It does not tolerate heat and does not grow well in urban areas. The Canadian hemlock has special significance to those of us in the ACS and to other gardeners. It was formerly a major source of conifer cultivars in the United States, and hundreds have been found and named. In the early 20th Century, it was the most common dwarf conifer in the garden of the keen collector.

The first conifer cultivar of our native eastern hemlock to find notoriety is Tsuga canadensis ‘Sargentii’ (Sargent’s weeping hemlock). It can now be seen at several arboreta in the Northeast, including: The Arnold Arboretum, Boston, MA, New York Botanical Garden, NY, Planting Fields Arboretum, Nassau County, NY, Longwood Gardens, Kennett Square, PA, and Bayard Cutting Arboretum State Park, Great River, NY. These specimens are over 100 years old. They are magnificent and well maintained. Other cultivars, whether of miniature, dwarf, or intermediate growth rates, offer textures and colors to the garden, which are quite different from those of pines, spruces, and firs.

Photos by Frank Goodhart

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

|

Transplanting Your Conifers

By Wynne Keller

August 23, 2019

Find out how to transplant your garden to its new home.

Wynne and Michael Keller's new home, and transplanted plants, on their wooded grounds

Uprooting the Conifers

Two years ago, we decided to leave our home of 35 years in central Maine. We planned to build a new place for our retirement, one closer to one of our sons and his family.

Living for so many years in one place, a gardener can create a lot of garden. And in the last 12 years or so, I had contracted Addicted Conifer Syndrome. I had collected a lot of treasured trees I did not want to leave behind, especially with no guarantee that a new owner would care about them, or even worse, might even want to destroy them. My husband and I resolved to move and transplant as much as we could to the new property.

Michael Keller moves a large conifer for its transplant

Our new home was not scheduled to be finished until December. That meant that we would have to create a new conifer garden while the house was under construction, and that we would have to transplant trees before the ground froze.

I began our search of transplant candidates by using my spreadsheet of my existing plants and marking the ones that I thought would be possible to dig. Since perennials can be split easily in spring with no loss to the appearance of a garden, I also included many companion plants.

Then, we eliminated anything which had been in the ground for 8 years or more. We also flagged some trees that we thought might be at risk if transplanted, or would concern any new owner because of its location, such as a pine growing way faster than I had anticipated it would or any tree too close to the house.

Still, that left a lot of trees.

The plants, in their process of being transplanted, were moved to their new home via our RV

Conifer Count

The total to be moved exceeded 125 plants, of which 58 were trees. The trees were mostly conifers and a few Japanese maples. We dug a few trees every week throughout the summer. Not all went smoothly. Some trees suffered considerable loss of roots, especially those in place for multiple years. Some also had been grown in spots, which made digging awkward. These trees received extra care all summer and after transplanting.

In order to get a conifer garden laid out on the new property, we hired Lee Schneller Fine Gardens of Camden, ME. Lee had designed a Japanese-style garden for us years ago at our existing home. We were not doing a Japanese garden this time, but we liked her aesthetic sense and style of working. We met at the new property, while the foundation was being dug. We devised a plan for a dry rock stream to border the woods and culminate in a wet zone, so as to take advantage of the slope of the property.

Before we could get the designer and the backhoe/bulldozer expert together to lay out the dry stream, 6 weeks had elapsed. Meanwhile, we kept digging, and potting, and watering, and tending, and moving plants from one property to the other.

Our potted transplants were placed in readiness for planting

Shaping the Conifer Dream

Construction day finally arrived, and we watched the dream begin to take shape. They dug the bed for the stream, laid in the weed barrier, and piled on stones. At the end of the stream, a large hole was dug to hold extra soil for the wetland plants. This hole would slowly drain down the hill, and retain water long enough to keep wetland plants happy.

By this point, we had moved most of the pots to the new property, and the crew spent two days getting the holes dug in the rocky soil, adding topsoil, and placing the plants. Our mission now was to keep everything alive. We watered weekly and created shade barriers for the more challenged trees. Fortunately, the well had already been dug. The only trick to watering was to make sure we were on-site often enough.

A view upstream from the wetland

Conifer Work in Progress

We had a huge rain storm in September, which flooded the entire front yard with about 4 inches of water. It turned out that the dry stream was not quite at the right slope to drain the yard properly. As a result, the front yard had to be dug up. The drainage pipe was laid, allowing water to empty into the wet zone. This is an example of the perils of landscaping before the house is built.

Over the first winter, we lost 4 trees. We predicted 3 would die, as these trees had not come out of the ground easily, and 1 was unexpected. On the other hand, some lived which I did not think would make it. Our garden is still just beginning, but it has a lot more trees than we otherwise could have had. We are excited about watching the garden grow, and about adding to our landscaping, all of which is a lot easier now that we live here!

Photographs by Wynne Keller; drone photographs by Peter McNaughton

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

ACS President

ACS President CR Director

CR Director ACS Secretary

ACS Secretary SER Director

SER Director CR President

CR President WR Director

WR Director ACS Treasurer

ACS Treasurer SER President

SER President WR President

WR President