|

|

Posted By Administration,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

By Sara Malone

October 17, 2021

Landscaping with Dwarf Conifers

A group of dwarf conifers in the Jordan garden in Oregon displays a dazzling array of texture, form and color

Why Dwarf Conifers?

Most of us think of flowering plants when we envision a garden or home landscape. And not just flowering plants as they are defined by botanists, which includes trees such as maples and oaks, but specifically plants with showy flowers: roses, lilacs, lavender, poppies and the like.

Approximately 20% of the U.S. population gardens, perhaps a little more if we include those who limit their gardening to food crops. Yet 65% of U.S. residents own homes, which means that some 45% of the population, or 148 million people, have yards, gardens or terraces and don’t, themselves, garden. If you are one of those people and you are wondering whether to plant petunias or poppies, lobelia or lavender, take a step back and think about beginning with structural plants that add interest all year long: dwarf conifers.

Conifers have gotten a bad rap for decades. Before dwarf selections were available, most conifers simply got too big for any but the grandest and largest gardens. Unfortunately, developers and landscapers often didn’t check the growth rate before they planted that cute little tree next to the house, which eventually towered over the roof, way out of proportion and shutting out all light, even in winter. Then there was the fashion in the 1970s of planting beds of nothing but conifers, generally crowded together and left unmanaged and unpruned. It’s no wonder that some people shudder when they hear the word. Others, unaware of the vast array of colors, shapes, textures and sizes available, can only think of Christmas trees.

This is NOT what we would suggest, but what many people 'see' when they hear the word 'conifer'. Photo credit, Wikipedia

Conifer Sizes and Growth Rates

Approach designing your yard or garden the way that you approach decorating your house: first comes the structure, then the furniture, then the knick-knacks, pillows and other decorations. Conifers represent the structure, perhaps some of the furniture. Flowers represent the decorations. It’s also similar to getting dressed; you put on your clothes and then accessorize with scarves or ties or jewelry. Again, those accessories are the flowers.

For the purposes of this discussion, when we say ‘conifers’ we mean dwarf conifers, which are selections that are slower growing than the wild plants that we find in nature. The ACS has identified four ‘sizes’ (really growth rates) of conifers. The most useful are those that are designated dwarf, which grow 1-6”/year, and will be roughly 1’ – 5’ after ten years. Remember, that is 10 years from the time that the plant was started; you will likely be buying a tree that is already several years old. Woody plants (those with trunks and bark) never stop growing, but their growth rates vary widely, and most will slow down as they mature. Arboretums and family estates must think about planting for the ages, but since we can’t control what happens to our gardens when we move away or pass on, it is generally most useful to think in terms of growth over a few decades when selecting individual trees.

This Cupressus macrocarpa 'Wilma' at the Mendocino Coast Botanical Garden brightens the landscape in late fall. Photo by Janice LeCocq

What Makes Dwarf Conifers Good Landscape Choices?

- They add year-round interest

- They are available in a wide variety of colors

- They are available in a wide variety of shapes

- Their new foliage and cones can be as decorative as flowers

- They require little care once established

Conifers add structure to the landscape and can be planted with other woody plants or flowering perennials as in this scene in The Oregon Garden. Photo by Janice LeCocq

Structure

Woody plants help define spaces in your garden. Hedges function as walls, and overhanging tree limbs can serve as a 'roof', providing shade and shelter. Individual shrubs or trees can provide ‘punctuation’, serve as a backdrop for showier specimens, and add texture and visual interest.

Even in the dead of winter, this dwarf blue spruce (Picea pungens 'Lucretia') is a rich, powdery blue. Photo by Janice LeCocq

Cryptomeria japonica 'Mushroom' is verdant in spring and summer but cold weather turns it a violet hue. Photo by Janice LeCocq

Year-Round Interest

Most (but not all) conifers are evergreen, which means that they will soldier on through the autumn and winter with green needles, providing color, texture and in some cases, privacy, while most of the landscape is bare. Whether you live in Minneapolis or Miami, Seattle or Sedona, some mix of evergreen and deciduous plantings provides year-round appeal and interest. Pairing deciduous trees that color dramatically in the autumn (such as maples) with blue-needled conifers can create breathtaking contrast.

Blue conifers play off the orange and yellow fall foliage, adding drama and excitement

Wide Variety of Colors

Conifers come in practically every shade of green imaginable, from pale gray green to bright chartreuse to rich emerald or earthy olive and finally the darkest, deep green. There are also many blue-needled conifers, with tones ranging from powder blue to silvery, and sometimes even with a teal cast. Some conifers appear almost gray, especially in sunlight. The showiest conifers have golden or yellow needles.

You've already seen blue, now check out yellow! This is the gold-dusted foliage of Picea orientalis 'Skylands'

Wide Variety of Shapes

There is a conifer for almost any shape you desire. Conifers can be narrow and upright, broad and spreading, ground-hugging, bun-shaped, weeping and everything in between. Study your garden and decide what shape, or mix of shapes, you want.

You can use our search feature to get ideas. Go to our home page and look for the 'Advanced Search' button. This feature will allow you to search for conifers by shape, color and size.

Conifer New Foliage and Cones Can Be as Decorative as Flowers

We all relish the arrival of spring flowers after what always seems like a long winter (although it won't seem so dreary if you have enough conifers in your garden!) You don't have to give up spring interest if you plant dwarf conifers, though. Click through the gallery to view an array of fabulous spring growth and cones. You won't be disappointed.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

By Web Editor

November 9, 2019

Find inspiration for your next conifer complements.

The conifer, Cis Korean fir (Abies koreana ‘Cis’)

I am sure everyone who has heard my nonsense knows that the best companion for a conifer is another conifer. If you were to pick one, the best one to pick is your favorite. Of course, my favorite is whichever one I happen to be standing by at the moment. Right now, I happen to be standing by Abies koreana ‘Cis’, so that is my favorite at this moment.

My garden is small, so to get 350 conifers in there you have to like small. Now can you believe people like other things besides conifers, even me, so that is where the other companions come into their own. I like to break it down into five categories trees, shrubs, perennials, (somebody told me rock garden plants were really perennials regardless of how small), hardscape, and people, yes, people.

A Stewartia koreana tree (Stewartia koreana)

Companion Trees for Conifers

First, are the trees. I don’t like many as “Conifer Companions,” but I like some and I bet you can add some to

my list. To start, I like small trees. There are not many of those, but an Aralia elata ‘Variegata’ fits the bill. You don’t see many in the U. S. and I like things that not everyone has. Heptacodium miconioides flowers very late

into September and the sepals, which are after the flowers, are better than the flowers. It also has white bark which gives it winter interest.

Another small tree you don’t see too often is the Chionanthus retusus which I call

my olive tree. If you have a female plant, it will get green fruit, (the olive part) that turns a very pretty blue. I like this tree quite a bit. My brother and I also have several Acer palmatum, but they are in a pot, which we bring in on our unheated

enclosed patio to keep them somewhat warmer in the winter. You see, they are not hardy in our part of Iowa. My favorite tree is our Stewartia koreana, which is the best tree we have in the garden. It flowers around the 4th of July, has great

fall color, and the bark is outstanding year around.

The dwarf shrub, blue mountain heath (phyllodoce caerulea)

Conifers and Complementary Shrubbery

There are many shrubs and I like to stay to the smaller size. The small daphnes are outstanding, and I

have about thirty of those. Also, the small heaths and heathers work well. Heaths for spring bloom and heathers for late summer bloom are both evergreen for year-round color. Stay with the smaller ones as some of the larger ones are too big for companions.

You may be surprised, but some of the rhododendrons work well. Rhododendron ‘Purple Imp’ and Azalea ‘Red Elf’ are two that come to mind, plus they are evergreen.

Now if you like a challenge, Cassiope, Phyllodoce,

and X Phylliopsis are what you want to give a try. They are very hard to find. They like acid soil and cool temperatures, which make them very difficult for me to grow in Oelwein, Iowa. There are other small shrubs that work well such as

Gaylussacia brachycera, Kalmia latifolia, Pieris floribunda and many others that I bet you have given a try.

The rock garden plant, Saxifraga 'Rose Marie'

Rock Gardens Plants and Conifers

Now for rock garden plants, or is that perennials? It’s up to you. There are so many of these it is hard to

know where to start or stop. To make it easier, I have a rule of thumb; the foliage cannot be taller than six inches. The flowers can be taller, but the foliage no more than six inches. We can’t have that foliage hiding our small conifers, can we?

A few that I like are Androsace primmuloides ‘Yunnanensis,’ Aquilegia jonesii, Draba athor, Erigeron hybrida ‘Canary Bird,’ Gentiana acaulis and of course, the saxifragas. One that I especially like is Saxifraga ‘Rose

Marie’ maybe because the flower stem is so short there is no chance to hide the conifer foliage. Now of course, there are many others that meet my stringent demands, but these are a few rock garden pants that I like.

From a gazebo to a

path, everything that is not a plant is hardscape to me. You might have a fire pit, gnome house, bench, or a stream, that all qualify. My favorite we have is a teaching tree. Many things can be hardscape, but I think our teaching tree says it all.

You can have a garden with a lot of neat plants, but you need hardscape to make it a true garden.

A teaching tree

Conifer Companions

Finally if you remember, I said in the beginning you need people. You have to have people to make the gardening experience

complete. These may be friends you have made at a regional or national ACS meeting.

It might be those that have visited your garden. Or it may be friends at a Rendezvous in the Bickelhaupt Arboretum. Wherever you make gardening friends,

they are the best friends you will ever have. So even though it seems impossible, there are other things besides conifers you can have and I hope you have a few.

Text and photographs by Gary Wittenbaugh.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

Conifer Bonsai Care

By Jack Christiansen

September 21, 2019

Learn how to care for conifer bonsai after its shaping. This is part 2 of the author's guide on shaping and caring for bonsai. Click here to read part 1.

This is an example of a conifer bonsai shape that can be achieved over years

Your first bonsai: keep it simple

When I started looking for my first bonsai plant, I had no idea of the various strengths or weaknesses of the many trees. Going to a nursery and choosing just any plant was my demise. I now know some conifers are temperamental and others are more forgiving.

For your first bonsai, choose a juniper, pine or cedar which are all good selections and which will withstand the type of treatment your plant will undergo. If your climate zone permits, you may want to try a spruce or a larch, as they make wonderful bonsai also.

The key criterion for a plant that is bonsai-adaptable is the leaf or needle size. The larger the leaf or needle size of a plant, the larger a bonsai tree must be, in order to achieve a good size relationship.

Close up of twists and contortions achieved by wiring a conifer bonsai

Post-Shaping Care

Once you are satisfied with the wiring and positioning of the trunk and branches, you should water your tree and set it aside in a protected and shaded area of your yard. Your plant has undergone unusual treatment and needs to be left alone to recover its vigor.

Gradually bring it back into full sun when the weather is not overly hot. You can then begin fertilizing the tree, making sure the plant is now putting on new growth. It usually requires two to three months after being wired and cut back until you can start making adjustments to the initial styling.

Usually, I won’t put a tree in a small bonsai-type pot until it has been styled over a period of several years. A large container will allow your plant to attain better growth and trunk size more rapidly. Once you are satisfied with the size, it is then ready for a nice bonsai container. Repotting should be done only when the plant has gone into a dormant state, in late fall, winter, or early spring.

Conifer bonsai Thuja occidentalis ‘IslPrim’ Primo® wired for five years

All bonsai trees are wired into position within the container. This anchors the tree in place and protects the small feeding roots of the plant when you are working on the tree and manipulating it. A good training pot has ample drainage holes that allow water to flow freely through the soil and out the bottom. Again, I suggest using YouTube for good examples of how to wire a tree into place within your pot.

If developing bonsai trees becomes your passion, and you truly enjoy it, you will find that, in time, you’ll have many trees in your collection. With an outdoor conifer garden, there is a lot of down time, with nothing to do but watch it grow. With a bonsai collection to care for, you’ll have a constant program of tending your trees that will keep you busy throughout the year.

Multi-trunk conifer bonsai styled as a wind-swept tree. Juniperus chinensis ‘Shimpaku kishu’

A Fruitful, Lifelong Pursuit

Every morning, I spend a couple of relaxing hours outside, working on my bonsai trees. This is the most cherished time of day for me, working on my trees and taking care of their needs. I’m also the president of our bonsai club here in San Jose, California. Many of my closest friends are club members.

Weekly, we attend workshops together and exchange information about our various experiences doing bonsai. My time outside in the environment of my conifer garden, along with having a large collection of bonsai trees, has brought me closer to nature and the joys of life. I hope that you will experience this same joy with bonsai.

I plan to share more articles that will take you even further with this wonderful art form.

Photographs by Jack Christiansen.

Jack is an ACS member, an avid bonsai-enthusiast and bonsai-creator. His garden is an excellent example of creative design and the integration of bonsai into the garden. His knowledge and photographic skills are well-known and widely appreciated. He lives in San Jose, California. Over the years, Jack has been a valued contributor to the CQ.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

Conifer of the Quarter: Taxodium distichum - Bald Cypress

By Jeff Harvey

June 29, 2017

Taxodium distichum - bald cypress

Taxodium distichum 'Cascade Falls' (Photo by Jeff Harvey)

Commonly known as Bald cypress, Taxodium distichum has always been fascinating to me. I have always liked the bark, and the natural shape is hard to beat, especially the silhouette in the winter time. They were designated the state tree of Louisiana in 1963. Native to wet and swampy areas of the southeast, they are very adaptable. You can find many growing in drier areas and even as far north as New York. One of the ways to tell Taxodium apart form Metasequoia is knowing your ABC’s. Fortunately for many of us, you only need to know up to C. Bald cypress leaves grow in a swirling pattern and originate alternately along the stem, so A is for alternating leaves, B is for bald, and C is for cypress. On the other hand, Metasequoia leaves grow opposite one another rather than alternating.

Taxodium distichum ’Jim’s Little Guy’(Photo by Sandy Horn)

One of the fascinating things about bald cypresses are the knees they make in wet conditions, known scientifically as pneumotosphores. Once thought to be a way of getting extra oxygen, they now are believed to be used in helping anchor the trees. Many trees have survived hurricane force winds. The knees are also prized by woodworkers and wood carvers. The wood is tight grained and very rot resistant. In the 1900’s, bald cypress was harvested for timber.

There have been a bunch of Taxodium seedlings and sports on the market lately. One, called ‘Twisted Logic’, was in the auction this year. Another twisted branched variety is ‘Crazy Horse’. Some choice witch's brooms include Metasequoia glyptostrobiodes ‘Matthaei’ and ‘Hamlet's Broom’ as well as the ever-popular Taxodium distichum ‘Secrest.' Other large varieties are Metasequoia glyptostrobiodes ‘Silhouette’, ‘Waasland’ and the dwarf Taxodium distichum ‘Pevé Minaret’. There are several weeping forms, including Taxodium distichum ‘Cascade Falls’ and ‘Fallingwater’.

Taxodium mucronatum ‘Oaxaca Child’ (Photo by Jennifer Harvey)

At our meeting in Chattanooga three years ago, Dr. David Creech gave a lecture on Taxodium. He also brought a bunch of numbered test plants he wanted distributed across the southeast to see how they did. Some were only labelled with a number, while others were named cultivars - ‘Jim’s Little Guy’ and one from Mexico, Taxodium mucronatum ‘Oaxaca Child’. In Zone 8, ’Oaxaca Child’ is evergreen, so he is really interested in how far north it is evergreen. Ours lost its needles in the winter but we have had no die back so far. The leaves do break dormancy a little later than our other Taxodiums. We are in Zone 7a.

David would like to know how both the named and numbered cultivars are doing, so please send your results to Dr. Creech at [email protected]. He would like to know what zone you are in as well as how yours is growing, whether there is any die-back, and whether it is evergreen in your garden.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

By Web Editor

November 22, 2019

What Is a Witches' Broom?

Delve into the world of the unusual broom-like deformation and why it is a prized rarity in conifers.

Witches' broom on a spruce (Picea)

A discussion of the various spellings of witches' broom (witch's broom, witch’es-broom, etc.) is for another article but a learned explanation can be found in the British Conifer Society Journal, Autumn 2015.

A witch’s broom may be a broom used by a witch in folklore (a Besom) but in its horticultural sense it is more familiar as a diseased or mutated mass of dense deformed twigs and foliage forming a birds nest-like structure in a tree or shrub. They are the source of some of our most choice and beautiful dwarf conifers.

Normally in plants, especially evident in trees, the leading shoot will produce an auxin, a plant hormone, which will slow the growth of the secondary and tertiary shoots to prevent them from overgrowing it. Interference in this mechanism by mutations or cytokinins (a phytohormone) induced by fungi, insects, nematodes, phytoplasmas, viruses or other outside agencies can cause plant apices to develop into witches' brooms.

The fungus Taphrina betulina is responsible for witches' brooms on downy and silver birch, and the fir broom rust Melampsorella caryophyllacearum stimulates bud formation to produce large numbers of disfiguring deciduous brooms on Abies concolor and A. lasiocarpa (white and subalpine firs) in the Rockies. A dwarf mistletoe, Arceuthobium douglasii induces massive hanging conglomerations of branches on Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) in California and Oregon.

There are many other examples, but we are more concerned in this article with the brooms caused by a genuine genetic mutation in a growing tip, not necessarily the leading shoot. These are likely to be stable and when propagated can make attractive dwarf or colorful new cultivars of horticultural value. Although they can occur in any plant, they are most often associated with conifers.

Witches' Brooms and Relevant Conifer Genera

Witches' brooms in conifers are normally associated with the Pinaceae (Abies, Picea, and Pinus in particular). They undoubtedly occur in other genera, but, maybe not so many, or are overlooked. Soft foliaged conifers like Chamaecyparis and Thuja will rapidly overgrow any mutation and they will be lost if not spotted quickly.

Many of these are color variations such as yellow or variegated white on a green plant; they are normally referred to as sports. Growth tip mutations can be color-changing or distorting, but the classic WB is a slow growing or dwarfing cluster of shoots. These obviously start small, and some stay very small, but in favourable conditions, not being shaded out or blown off the tree, they can reach great ages and size. Typically one will see a ball of irregular foliage a foot or two across. Occasionally, they will reach 4–5 (-6 or more) feet across and may be fifty years old.

Common Conifer Terrain for Witches' Brooms

My favorite was a huge broom over a metre across in a Scots pine by the side of a major ‘A’ road near Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England. Obviously, pretty old in 1980, it took a good few years of trying pieces before I managed to get a graft to take. Older brooms are notoriously dry and sometimes difficult to graft successfully. It made a nice little plant, but I am still hoping it will eventually produce little green cones like the ones which studded the parent broom.

Although WB’s are not uncommon in the UK, they are more typically found on conifers in countries with more serious mountainous areas. High altitude seems to trigger more brooms, as you might expect from higher solar radiation causing more mutations. One can drive around in the mountains of Colorado above 8,000 feet and see a broom or two in the roadside conifers every 328 feet. Getting at them is another matter. The best are always out of reach. In the early days, legend has it, that the European collectors would blast the brooms down from high in a tree with a shotgun, a practice continued today in the States.

The resultant beautiful little conifer of Picea abies ‘Wichtel’ about 8 inches across after some 7-9 years

Witches' Brooms as a Worthwhile Hobby

There have been collectors of WB’s for a long time now, but I suspect the early ones were only on a casual basis because of time and transport limitations in the early 1800’s. More recently, in the last thirty or so years, collecting became more intensive and has started to produce a new generation of really dwarf plants which will eventually be so useful as genuine miniature trees in rock garden work and the smaller gardens of today.

There are three main areas of the world where WB’s are being hunted; The Rocky Mountains and Cascade Ranges in the USA and central Europe. There are some, questionably obsessive, collectors of WB’s who seem to have spent a large part of their lives in the mountains hunting for ever slower growing little plants. Some have found and named or listed over a thousand WB’s and entered conifer folklore: Jerry Morris from Colorado is one, mostly collecting brooms on Abies lasiocarpa, Picea engelmannii, Pinus flexilis, and P. contorta, all at fairly high altitude. In Europe, German, Czech and Polish collectors are combing the Alps and especially the Tatra Mountains for Picea abies and Pinus mugo brooms. This is where the really tiny dwarfs seem to be coming from.

Witches' Broom Nomenclature

Newly discovered brooms in the wild and the subsequent grafts from them are often numbered with a hash number. So, if 9 different brooms have yielded scions in a particular area, they will be numbered #1 to #9. The prime example is the San Seb(SS) series of up to 1,000 numbers given to dwarf plants from different brooms collected by Milan Halada and Jan Beran from trees of Pinus mugo subsp. rotundata in the San Sebastion region of northern Bohemia (Czech Republic).

One suspects that there must inevitably be some duplication with the same mutation occurring more than once. Many will fall by the wayside, but the best will be named and propagated; SS #25 is a choice tight dark green bun now named P. m. subsp. rotundata ‘Beran’. The finder usually coins the name, which accounts for some wonderfully eccentric ones.

Names are often given after the place of origin. One of the most informative and nicest is Pinus flexilis ‘Tioga Pass’ (above Yosemite National Park), a wonderfully evocative place if you have ever been there. The wild brooms themselves are sometimes labelled to ensure they are not collected from on multiple occasions by another collector or two. It is important to take only a small part of the broom and leave some scion wood for another year in case of failure.

Propagation of Witches' Brooms

Brooms can occasionally be propagated by rooting cuttings, Picea abies in particular, but normally they have to be grafted. The normal compatibility rules apply: Picea scions onto Picea abies rootstocks, sometimes P. sitchensis, Abies onto A. alba in the past, but mostly onto A. koreana nowadays. Five needled pines onto P. wallichiana or P. armandii, P. strobus having fallen out of favour due to plants “miffing off” in our mild damp climate. Two needled pines onto P. sylvestris, P. mugo, or P. mugo var. rostrata.

Knowing the origin of the stocks may be important when it comes to siting plants: We received part of a beautiful Scots pine broom from near Madrid, Spain with the comment that it would be a very good plant for a hot dry climate. Maybe it would, but we graft it onto Scots pine rootstocks sourced from a Northern Scottish clone so that its roots will be happy in our long damp UK winters.

Some species are very prolific; others rarely produce WB’s. The European mountain pine, the P. mugo/P.uncinata complex, has thousands of different dwarf “cultivars” derived from wild collected brooms, but there are hardly any named ones of P. pinaster in spite of the millions of trees around the Mediterranean.

An unnamed graft only 5cm across from a tiny WB consisting entirely of buds only

The Close Relationship between Witches' Brooms and Dwarf Conifers

One novelty source of new WB’s is to find them on existing dwarf conifers. It’s perhaps not so surprising as the plant must already have had a propensity for mutating. Mature plants grown from WB’s sometimes start to produce cones with viable seed. Even smaller plants have been grown from them.

The Victorian desire for little trees to complement their Lilliputian rock garden landscapes started them looking for new, dwarf, cultivars. Some were selected slow growing seedling mutations, but many were propagations from WB’s. Their penchant for collecting things also fuelled the quest for more variety and ever more dwarf plants, aided by interest from Continental nurserymen, a craze that is continued today.

The best example was seen in the world’s reputed earliest rock garden at Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, dating from 1820, which, in about 1980, had two specimens of Picea abies ‘Pygmaea’ which had reached over two metres after an estimated 140 years (now, sadly, removed). These were almost certainly derived from a WB, as was the other classic example; the earliest recorded dwarf conifer; Picea abies ‘Clanbrassiliana.'

Seeking Slow-Growers

Planted by Lord Clanbrassil in 1798, the original is still alive in Tollymore Park, Newcastle, County Down, Northern Ireland. The illustration shows one of its earlier plantings growing at Eastnor Castle, Herefordshire. It is now a 17 feet specimen after about 150–200 years. A point that should be noted by all those who ask “How big does it get” when contemplating buying a dwarf conifer.

A similar, highly recommended, dwarf pine arising from a WB which has been around for many years, and many will be familiar with Pinus sylvestris ‘Beauvronensis.’ A fine example of an old specimen can be seen in the Heather Garden at Saville, Windsor Great Park, England. Although slow, it is now over 17 feet high. There is a tendency for dwarf or slow conifer cultivars derived from WB’s to grow faster over the years as the now missing leading shoot growth hormone inhibition has less effect.

These large ancient specimens have obviously outgrown their miniature tree status even though fresh propagations from them would remain useful slow growing little trees for many years. It illustrates why even slower growers were, and are still, sought after.

Modern Hunters of Witches' Brooms

One of the main objectives of WB collectors today is to find the slowest growing WB to produce the tiniest little plant. The limit seems to have been reached by the discovery of more than one broom consisting of simply a tight cluster of buds with no shoots. You would expect a real carpentry problem grafting a small piece, but to their credit they seem to find ways.

The most enthusiastic collectors are not concerned with aesthetics and will usually graft slightly higher on the stock (6– 9 inches) than looks right. This produces an ugly little lollipop which is easier to keep clean and weed-free, but can take many years to grow into a shapely object of desire for the garden. Having said that, deliberately grafting slightly larger growing, but still dwarf, pines and piceas onto a rootstock at 20–30 inches can produce a really attractive novelty dwarf plant on a stem which can add height and interest to a rock garden or trough, while allowing the under-planting of alpines.

Normally, one would graft as close to ground level as possible, to form a better plant and partly to hide the graft scar. Most WB’s will form a bun with varying degrees of tightness, many very attractive, when propagated. Personally, I prefer a miniature tree, with a visible trunk and some “architectural” qualities along the lines of the original Victorian concept. Either way, the best are ideal for troughs and really miniature gardens or garden railways and can do away with trimming for many years!

A creamy sport on Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Tsatsumi’

A Closer Look at Dwarf Conifers

For the future, there will soon be a new generation of more dwarf pines and spruces than were available in the past. Typical is Pinus mugo ‘Meylan’ a WB found on a plant of the old favorite “dwarf” Pinus mugo ‘Mops’ which nowadays tends to get too large. There are many more of these lovely neat little dwarf buns to come, look out for them in the more specialist nurseries and eventually the garden centers, but don’t expect to find all the names in the literature though.

Not all the plants derived from brooms are just dwarf with little colour variation; there are some good, bright yellow, little pines and dwarf blue spruces or oddly shaped novelties as well. Examples of plants for the future would include Picea pungens ‘Bali’ and ‘Porcupine’, the two little plants illustrated are growing in Jan Beran’s Czech garden from WB’s found in the States.

There are many more of these really dwarf blue spruces slowly becoming available. Pinus contorta ‘Frisian Gold’ found as a WB before 1962 by the Zu Jedelloh nursery is an example of a golden yellow pine. There are quite a few more, mostly P. mugo forms, many much smaller and neater to come in the next few years. A really stunning plant slowly becoming available is Abies koreana ‘Kohouts Icebreaker’. This was found as a WB on a plant of the already popular A. koreana ‘Silberlocke'.

Many of you will be familiar with the bright creamy white of the recently introduced pyramidal Picea glauca ‘Daisy’s White’. For the real enthusiasts there is now a more dwarf little globe of cream, P. glauca ‘Jalako Gold’ which was found as a tiny witches' broom on a plant of ‘Daisy’s White’. It will be scarce for many years.

A Long-Term Passion Project

A note of caution, selecting from all the thousands of witches' brooms can take many years of evaluation and deciding whether a plant is good enough or different enough to be named and propagated. Time moves slowly in this world though and, even after that, it takes many more years to multiply up enough stock and bring something new to the gardening public.

Some, especially the dwarf and choice, will always remain as collectors’ items because there is a limit to the number of scions available every year from a dwarf, slow plant producing only a few tiny branchlets. The slightly larger growers stand a chance of being commercial and setting plants onto the garden centre benches twenty or more years after being found.

Text and photographs by Derek Spicer.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Conifer Quarterly.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

Fertilizing Conifers

By Web Editor

November 22, 2019

Dr. Bert Cregg of Michigan State University answers frequently asked questions on feeding your conifers.

Nutrient deficiencies in conifers are linked to site factors such as unfavorable soil pH

Nutrient deficiencies are a common cause of reduced growth or poor appearance in many plants, and conifers are no exception. Unfortunately, the Internet and other sources are full of home remedies for nutrient deficiencies that are of dubious value as well as other misinformation about plant nutrition and proper fertilization. Below are some of the common questions which arise when dealing with nutritional issues in conifers.

What nutrient elements are needed for conifers?

Conifers, like all plants, require 16 elements for normal growth and development. Plants obtain three of these elements; carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, from air and water. These three are not considered when discussing nutrients which must be obtained from the soil. The remaining elements are grouped based on the relative amounts contained in leaf or needle tissue.

Macronutrients are elements which occur in relatively large amounts, usually 0.1 to 2.5% of leaf dry weight. These are nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, sulfur, and magnesium. Micronutrients are elements needed in relatively small amounts, sometimes as little as a per million of leaf dry weight or less. These elements are sometimes referred to as trace elements and include: iron, boron, manganese, molybdenum, copper, zinc, and chlorine. See table for abbreviated elements.

Are there certain elements commonly deficient in conifers?

Conifers, especially evergreen conifers, typically have lower nutrient requirements than deciduous broadleaved trees since evergreens don’t have to produce an entire new canopy of leaves every year. The likelihood of encountering nutrient deficiencies depends on several factors including the type of conifer and soil conditions.

In general, micronutrient deficiencies are comparatively rare since plant need for these elements is low, and most soils can supply them in adequate amounts. Some exceptions are iron and manganese, which can occasionally become deficient as soil pH increases. Nitrogen can become deficient since it is the element plants need in the largest amounts. Also, nitrogen is very dynamic in soils and can be lost by a variety of ways such as leaching, volatilization, and denitrification.

Magnesium and potassium can sometimes be limited in sandy soils that have a low cation exchange capacity and, therefore, a low ability to retain these nutrients. Phosphorus availability in soils varies widely around the country and even between locations within a region. Because excessive P can contribute to surface water pollution, it is important to establish a need for P before applying P fertilizer. In fact, some states have banned P fertilizers for homeowners, or require a soil test before applying P fertilizer.

How do soil properties influence plant nutrition?

Plant nutrient availability is inextricably linked to soil properties. Discussing all the soil factors which impact plant nutrition is beyond the scope of this article, but there a two key soil properties critical to dealing with plant nutrition; soil pH and soil texture.

For most plants, the optimum soil pH is around 6.5. This is because the availability of some elements decreases as pH goes above 6.5 while others decrease as pH goes below 6.5. For conifers, this “sweet spot” of soil pH is lower than for deciduous trees, usually 6.0 or even a little lower. Soil texture describes the relative proportion of sand, silt and clay particles in a soil. Ideally, soils should have a mixture of particle sizes since sand provides porosity and air space while silt and clay contribute to water holding capacity.

Clay particles, along with soil organic matter, also contribute to cation exchange capacity (CEC). CEC refers to the ability of a soil to act as a reservoir for important nutrients such as K, Mg, Fe, Mn, Cu and Zn. Conifers grown in very sandy soils with low organic matter have a potential to experience deficiencies of some of these elements.

How do I diagnose a suspected nutrient problem?

Diagnosing a suspected nutrient problem in conifers often requires some detective work. Visible symptoms expressed by a plant are usually the starting point. There is a common misconception that nutrient deficiencies can be diagnosed by simply matching the plant symptom to an image in an extension bulletin or website. In reality it’s rarely that simple. Several nutrient deficiencies can result in symptoms that look similar; N, Mg, and Fe deficiencies can all result in chlorotic (yellow) foliage.

It is also possible that symptoms may not be related to a nutrient problem at all. Drought, heat, insects, herbicides and other factors can produce symptoms that can be mistaken for nutrient problems, so it is important to eliminate other causes. A soil test that includes soil pH is a minimum requirement to adequately assess a nutrient problem. In many states, soil testing is available through university extension services, as well as through private labs.

Detailed instructions for collecting and handling samples are usually provided by most testing labs. The key step to remember is to collect a series of samples which are representative of the area where plants are having issues. Many university extension labs and private labs also perform foliar nutrient analyses. These will show the actual concentration of the essential nutrients in the leaf tissue. Again, detailed directions on sampling are available from most labs.

Foliar sampling is particularly useful in nurseries and large landscapes where it is possible to sample “good” and “bad” specimens of the same species or cultivar. By comparing the foliar test results of the two samples, nutrients that are deficient will often become apparent.

Foliar symptoms such as yellow (chlorotic) needles may indicate a nutrient problem but soil or foliar sampling are often needed to identify which element is limiting

Should I fertilize my conifers?

With increased public concerns over the impacts of excessive fertilizer nutrients on our surface waters, the days of recreational fertilization are over. Fertilizers need to be applied with a purpose. This requires identifying a specific deficiency through visible symptoms, a soil test, a foliar test, or, preferably, a combination of at least two methods.

When should I fertilize conifers?

Fertilizer nutrients are most efficiently taken up when roots are actively growing. For most trees, including conifers, this usually means during the spring. Avoid fertilizing in the summer to reduce potential volatilization in hot weather. Fertilizer can also be applied in the fall after budset, but there is potential for leaching if using a nitrate-based N source.

If a soil test indicates that soils are deficient in potassium, muriate of potash (KCl) is a commonly-used source of K. This is a fertilizer which has a high salt index. It is often applied in the fall to reduce the potential for fertilizer burn and to allow excessive chloride to leach out with rainfall and snowmelt.

What is the best fertilizer to use?

The best fertilizer to use is one that meets plant needs based on a soil test or foliar test. Where possible, look to use a fertilizer which addresses more than one need. For example, if plants are N deficient and soil pH is above optimum, a fertilizer that contains ammonium sulfate can help to add nitrogen and reduce soil pH.

Avoid applying excess elements that are not needed. For example, if plants are deficient in N, but a soil test indicates other nutrient are sufficient, use a source such as coated urea rather than a complete fertilizer such as 10-10-10, which will provide excess phosphorus and potassium that are not needed.

How much should I fertilize?

Most soils labs will provide fertilizer recommendations along with soil test results. This will usually include a recommendation for N along with any soil element that is deficient. Labs that are accustomed to working with homeowners may report fertilizer recommendations in pounds per 1,000 sq. ft. of ground area. So, if you have a landscape bed that is 10’ x 25’ (250 sq. ft.), you would multiple the recommended amount by 250/1,000 or 0.25.

Many agricultural labs will provide recommendations in pounds per acre. The key number to remember is 43,560 - which is the number of sq. ft. in an acre. So, for our 250 sq. ft. bed, the conversion is 250/ 43,560 or 0.006. Also, an internet search of “area conversions” will link you to many useful calculators.

How can I adjust soil pH?

If a soil test indicates that pH is lower or higher than the desired range, it may be possible to adjust pH either by adding lime to raise the pH, or applying sulfur to lower the pH. Most soil test reports will supply recommendations for lime rates to achieve a desired pH. In general soil pH adjustments will be easier to accomplish on coarse soils than on clay soils.

Liming is most effective when lime can be incorporated into the upper surface of the soil. For this reason, lime is often applied as a pre-plant adjustment. Surface application of lime after plants are established can be effective, but the effect will be much slower than if lime is incorporated. In agronomic crops applying sulfur to lower pH is less common than liming to raise soil pH, so soil testing labs may not provide recommendations for lowering pH.

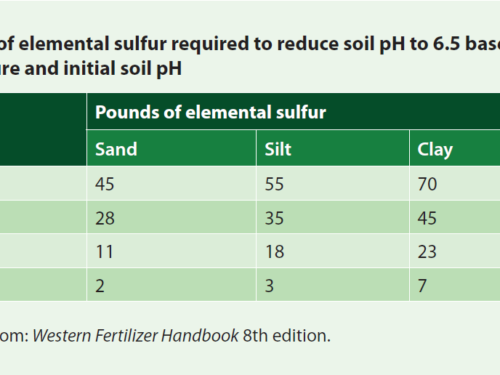

The table provides some general guidelines for using elemental sulfur to lower pH. Soil pH can also be reduced by applying urea, ammonium sulfate or other ammonium-based fertilizers. Conifer gardeners may also apply products such as Holly-tone or Miracid to adjust pH. When using sulfur or fertilizers to lower pH, keep in mind that soil acidication is accomplished by soil microbes. So, it may take a year or longer to see the desired impact.

As with liming to raise pH, it is typically harder to affect a change on a clay soil than on a coarse soil. Lastly, the effect of the sulfur on pH is transitory and pH will drift back up over time, so be prepared to follow up with additional soil tests and re-adjust every three years or so.

Needle chlorosis in Mugo pine (Pinus mugo)

What is a fertilizer analysis?

Fertilizer analysis (or grade) refers to the chemical composition of a fertilizer. By convention, fertilizers are classified by three numbers such as 10-10-10, which represent the amount of N, P, and K in the fertilizer. The first number is the % N in the fertilizer. Thus, if a soil test recommended 1.5 lbs. of N for a 1,000 sq. ft. bed, we would need to add 1.5 / 10% (1.5/0.10) = 15 lbs. of product.

For P and K the numbers are little more complicated. The second number is the amount of P as phosphate (P2O5), and third value is the amount of K as potassium oxide (K2O). Fortunately, most soil tests will provide a recommendation based on the amount of P2O5 and K2O, and many commercial fertilizer bag labels now express the analysis in both the traditional N-P2O5- K2O format as well as actual elemental concentration. And, if all else fails, a quick internet search of “fertilizer calculator” will link to a number of excellent university extension sites.

What about foliar fertilizer?

Foliar fertilization refers to the application of liquid fertilizer directly to the foliage of plants to remedy a nutrient deficiency. Growers apply foliar fertilizers in certain horticultural applications such as bedding plants in order to overcome specific deficiencies and prepare plants for sale. Most conifers are poor candidates for foliar fertilizer because the thick, waxy cuticle on their foliage is a barrier to nutrient uptake. In certain situations, micronutrient deficiencies in conifers may be addressed with foliar fertilization, but a better approach is to understand and address the underlying soil nutrient or pH issues.

What about organic fertilizers?

Organic fertilizers include a wide array of products that supply nutrients from living or once-living sources. These are in contrast to most standard inorganic fertilizers produced synthetically. Some examples of organic fertilizers are composted manures, fish emulsions, bone or blood meal, and Organic Materials Research Institute (OMRI) – approved pelletized organic products.

We have conducted trials growing conifers with OMRI-approved and conventional fertilizers at Michigan State University and, given the same amount of nutrients, trees grew similarly and had similar foliar nutrition with both types of products. Some factors to consider in using organic products include material handling (organic products usually have a relatively low analysis so more product needs to be applied) and odors and attractiveness to animals for products such as fish emulsion or blood-based products.

Summary

Most garden soils can provide adequate nutrients to grow quality conifers. When nutrient problems occur, try to identity the underlying cause, which usually requires a soil test including soil pH. If fertilization or soil pH adjustment is recommended, focus on addressing the principle issue and avoid applying fertilizer elements, especially P and N, if they are not deficient. This will help to keep your conifers looking healthy and protect the environment.

Text by Dr. Bert Cregg. Photographs by Petr Kapitola.

Dr. Bert Cregg is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Horticulture and Forestry at MSU.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

2022 Iseli Award - Accepting Applications

By Web Editor

December 13, 2021

Jean Iseli, the founder of Iseli Nursery. Photo by Don Howse

The American Conifer Society is accepting applications for the 2022 Jean Iseli award, a $4000 annual grant made to a public garden, arboretum, or horticultural institution that emphasizes the development, conservation, and propagation of conifers, with an emphasis on dwarf or unusual varieties.

Jean Iseli was an ACS founder and conifer propagator. This award was established in 1986 in his name.

Iseli Nursery pledges to grant the winner a 50% discount on any plants purchased in conjunction with this award, up to $8,000.

Proposals must include:

- Name, address, and phone number of the applicant/institution

- Brief description of the plans to utilize the funds

- List of conifers to purchase

- Budget

- Short overview of the mission statement or horticultural background of your institution

Send applications by email to [email protected], or by USPS to:

Ethan Johnson

39005 Arcadia Circle

Willoughby, OH 44094

Deadline for submissions is March 19, 2022. The Iseli Award committee will announce the winner in April, 2022.

List of Prior Award Recipients

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

How To Start a Tree Nursery

By Robert Fincham

December 8, 2021

The Bloom Garden Centre, in Bressingham, UK (USDA Zone 9), is a retail garden center in England showing a method of displaying their conifers.

So You Want To Start A Nursery

Text and Photography Bob Fincham

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, my late wife Dianne and I owned a wholesale nursery in Oregon, while also making retail sales through Coenosium Gardens. I used to mail a quarterly newsletter to our customers about the nursery, sale specials, and plant stories. A few of the readers of this article may recall this newsletter: Mitsch/Coenosium Notes.

One of the articles responded to a common question from our retail customers who wanted information about starting a nursery. I felt it was appropriate to resurrect and update the article I wrote about that same topic. Specialty conifer nurseries used to be more common than they are today. There are advantages and disadvantages to starting such an operation. If the reader is thinking about doing something along these lines, perhaps reading this article will help in the decision making.

I have had many discussions with individuals who were thinking about starting a nursery. A tour of a nursery greenhouse and gardens filled with many different plants is intriguing and looks like fun. It looked that way to me in the early 1970s, and Coenosium Gardens started as a hobby that got out of control.

The very first question to consider is why enter the nursery business in the first place. Sometimes a person chooses the nursery business as a career from the start. They either always enjoyed working with plants or were part of a family business.

I have found that those who enter the nursery business as a career change do so for various reasons: dissatisfaction with a present career, the loss of a job, the need to do something less stressful, or retirement from another profession. Whatever the reason for changing, financial improvement is seldom a primary consideration. After all, the nursery business is a form of farming, and few farmers amass much wealth.

I knew most of the nurserymen when I started collecting rare conifers. They were running their nurseries as more of a hobby/business endeavor. Most of them wanted to gain extra income from their hobby while trying to enjoy it more fully.

It is essential to decide if the nursery business is a sideline or a full-time business, providing income for your livelihood. This choice will determine the answers to many questions about your market and the product you choose to grow.

One exciting facet of the nursery business is the friendliness of the people involved. There are very few firms or trades where a person starting out can obtain advice and assistance from competitors. The nursery business is such a field, within limits. I’ve had people visit and ask us how to do many specific things related to plant propagation. When they asked for free scion wood to start a propagation nursery, they did not understand why I said no. Most nurserymen are more than willing to lend a helping hand to the novice, provided, of course, that the newcomer is making a substantial effort on his own behalf. No nurseryman will allow himself to be taken advantage of.

My own retail garden center from my days living in Eatonville, WA (USDA Zone 8a). I had found a good niche doing mail order sales with some local sales. Seen here are the greenhouse at Coenosium Gardens.

The first decision most people make when entering the nursery business is about what to grow, what they like, not necessarily what they can sell.

For example, a person enjoys growing fruit trees in a home orchard and has even grafted different varieties onto some of his trees. So, the grower invests in a piece of land and lines out some young fruit trees. He figures that when the trees become large enough, they will be sold for a profit.

This same story can apply to just about any facet of the nursery business. Take the person who completes an extension course and decides what to grow through discussions with classmates and the instructor. Unfortunately, just like the orchardist, this person has put the cart before the horse. Unless a person takes a very systematic approach to enter the nursery business, the results can be disastrous. A neglected field of poorly grown stock becomes choked out by weeds, or, just as easily, an area of beautifully nurtured but unsold plants can be the outcome.

Several decisions must be made by the aspiring nurseryman. They do not necessarily have to be made in the order presented, but they have to be made.

A person should decide if they are going to have a wholesale or retail operation. There are fundamental differences between the two. The wholesale nurseryman must grow many plants of only a few varieties while dealing with a relatively small number of customers. This kind of nurseryman will be able to concentrate almost entirely on growing and working with the plants.

Seen here are the rear of the holding houses and the greenhouse at Lehighton, PA (USDA Zone 6a). The flattopped holding houses collapsed in a winter rainstorm; one of many rookie mistakes.

.

Retail nurserymen handle a smaller number of plants with a wide variety. They deal with a much larger customer base than the wholesaler. Retailers must be more of marketing experts and know the growth requirements and landscape uses of a substantial number of plants.

Suppose a person enjoys working with many different people daily and a wide variety of plant material. In that case, the retail plant business should be considered. Suppose a person does not like to spend a lot of time selling plants and prefers concentrating on the nursery’s farming aspects. In that case, the individual should be a wholesale grower.

A newcomer to the nursery business must choose one or the other. Trying to do both retail and wholesale will usually mean that neither is done very well. There is too much dilution of effort. An experienced nurseryman can consider combining retailing and wholesaling into one operation, but care must be taken. A wholesaler does not want to compete with one’s own local customers by opening a retail area. Likewise, a retailer who opens a wholesale department will find many of retail customers expecting to make wholesale priced purchases.

Once the retail/wholesale decision is made, then marketing must be considered.

A course on marketing at a local community college can be a good investment for the new nurseryman, especially since marketing involves several parameters. Where are the customers located? The plants must be suited to their tastes and growing conditions. Where are the competitors? A retailer must be most concerned about the local competition, while a wholesaler must deal with local and distant competition. What kinds of plants are lacking in your marketplace? Are any of these things that the nurseryman would like to grow? How can a market be created for some of the items that you want to grow?

The decisions up to this point should have provided some direction about selling what is to be grown. Now it is time to make some specific determinations about the crops. The wholesaler may do some brokering but will produce the majority of what is to be sold. He must grow large quantities of relatively few items. The nurseryman must be a successful farmer as well as an astute businessperson.

On the other hand, retailers will purchase much of what they sell, growing a much smaller percentage of their crop than the wholesaler. They must work with relatively small quantities of many different varieties. However, even so, some growing is beneficial since some costs can be reduced. With a good plan, the retailer won’t have to worry about shortages of choicer plants.

My first greenhouse, Lehighton, PA (USDA Zone 6a), was built out of 2 x 4’s and poly. It was heated with a coal stove and sufficed until we moved to Oregon in 1986. My investment to start my nursery was minimal.

Marketing studies will help both the retailer and the wholesaler decide what material to offer for sale. The wholesaler should take things at least one step further. Attending a local trade show will provide a lot of useful information. Obtain catalogs from as many distributors as possible and find out what they are growing. Look for everyday items. Those are things that must sell well. Talk to the growers and find out what they have sold out of. Talk to other buyers and get a feel for the kind of things they want to purchase. Having open eyes and studying what others are growing will help determine what to grow. Most of what growers produce may be based upon other criteria; sometimes nothing more than gut instinct.

Do not just go to a nursery in your area and ask them what you should be growing. Do not ask a future competitor for their own unique methods of producing salable plants.

If you decide to be a grower, either as a wholesaler or as a retailer producing part of your own merchandise, you must obtain liners. Liners are the young, immature plants that will be grown into a salable product.

Liners must either be purchased from a propagation nursery or propagated in-house. Unless you are willing and able to expend considerable capital in obtaining stock plants and constructing propagation facilities, purchasing is a much wiser choice. With so many other things to learn, learning the art of propagation could dilute your effort. In many cases, in-house propagation is not as cost-effective as purchasing liners. The propagation nursery will also help make some decisions about items to grow but only if asked about specific plants. Even then, since a propagation nursery is not a grower, there is some guesswork involved.

If you have decided upon retail, you must determine what market niche you want to occupy. For example, do not try to specialize in one-gallon junipers and azaleas in an area where big box stores sell the same or similar items. Consumers shop for those items, and the small nursery cannot compete with the big box store’s buying power or prices. The smaller retailer must offer service and a product line unavailable at the big box stores. Do not ignore their store material completely. Carry some of their items to complement your main line.

Likewise, the small wholesaler should not specialize in commodity items (fast-growing, gallon material). The big commodity producers can profit by selling these plants cheaper than the small grower can raise them. Besides, commodity items are easy to produce and grow, leading to cyclical gluts and price wars between the big producers.

With smaller yards and a more plant-oriented public, homeowners are becoming more discriminating about their landscapes. Many small retail nurseries do quite well specializing in dwarf conifers, trees, and shrubs. The retailer must be well versed in the product to have good sales. Even a willingness to install small garden landscapes may be necessary for some parts of the country.

Bonsai have also become quite popular throughout the country, and some nurseries specialize in bonsai-suitable plant material. The retailer must be knowledgeable about the subject and must even be willing to arrange classes for his customers. A finished bonsai commands a high price to compensate for the labor involved in producing it, which often makes it a complicated item to market.

One major problem faced by all nurserymen at one time or another is how to handle unsold stock. Since plants are living, growing things, they always need more space. When plants are not sold within an allotted time period, they can clog the entire nursery. Be prepared to burn or discard more than a few plants almost every year when they do not fit selling cycles.

Having a special sale does not always work. Customers become conditioned and will often wait for these special times to buy plants, especially if end-of-the-year sales become a standard feature. Work with a few re-wholesalers who will take back plants that have outgrown your marketing scheme, in order to recoup some income. Or simply destroy the plants. Taking a smaller loss now is preferable to the more significant, long-term loss of being forced to use frequent sales to move plants.

The most serious difficulty for the nurseryman is debt. Avoid it. Sometimes debt is necessary to get through an occasional slow period in the economy, but borrowed money must be repaid. Suppose a nursery is servicing a large debt. In that case, that debt becomes a sponge, soaking up a considerable portion of a tight profit margin, under which all nurseries operate.

When starting a nursery, scale it to fit your expertise and budget, being careful that the two balance each other.

Gee Farms is a large, retail, rare conifer nursery in Stockbridge, MI (USDA Zone 5b), that is popular with ACS members. This picture was taken in July 2012 at the ACS National Conference in Ann Arbor, MI.

If you want to start a nursery, do your homework first. Growing and selling plants can be an enjoyable and very satisfying experience. Although it is seldom rewarding in a significant financial way, it is rewarding in ways that cannot be found on a spreadsheet. These other rewards should be the ones that make you want to be a nurseryman.

Coenosium Gardens is an example of the third type of nursery that is a modification of the retail nursery model I discussed earlier. It was a hobby nursery started by Dianne and me in 1979. I will mention a few things about its history as a model for any hobbyist who might be thinking of trying something similar.

It was during the summer of 1978 that I got the idea of starting a conifer business. I wanted to collect rare conifers. I had known for some time that I could not keep buying conifers on a teacher’s salary without some additional income. I also realized that I could not get collectors to share some of their treasures without offering something in trade. On top of it all, I had recently lost a few irreplaceable plants to rabbits. I needed a way to have back-up plants for rare ones that I had lost.

I had several significant decisions to make that spring and summer of 1979. First, would I graft to order, or would I sell from available inventory? I decided to do both. The new grafts would be shipped after June 1, while the older plants would go out in mid-April.

The second decision involved naming my new business. In 1980 I studied a dictionary of plant terms to find a name. I got to the C’s and came across the word Coenosium. It meant “plant community”. I figured that would be a great name. It was a name that would be unique to my nursery since nobody in their right mind would use a name that no one could pronounce.

My third decision involved advertising. I mimeographed my first plant list with brief descriptions and mailed it out to anyone who wanted it. I advertised in the publications of several plant organizations to find these people. I sent out over a hundred lists and got quite a few shipping orders in the spring of 1983. It would be my first shipping season. A year later, I published my first real catalog with pictures. The catalog that resulted set a standard. There was no catalog at the time of rare and unusual conifers for retail sales that included pictures.

I had converted most of the lawn area on our 2/3 acre into conifer gardens. Those gardens supplied the scion wood for propagation. I also had two blocks of container plants that I enclosed with white poly for the winter. Collectors used to visit regularly and were always so happy to leave with a load of rare conifers. They came from as far away as Cincinnati, OH.

Coenosium Gardens’ mail-order was proving to be successful and operated for thirty-four years. It was never a sole source of income but worked very well at paying its own way and financing my hobby.

Large wholesale conifer nurseries must limit their range of conifers to produce large numbers of fewer varieties. This one is in The Netherlands (USDA Zone 8a). Specific location unknown.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Admin,

Wednesday, June 7, 2023

|

November 3, 2019

Discover low-water conifers for the Western region, and beyond.

The conifer, Siberian cypress (Microbiota decussata) in winter color

What thrives in New England languishes in Georgia, and what over-winters happily in California succumbs to brutal Minnesota ice and snow. Like those of taxonomy, regional distinctions can be “split” or “lumped”, and by creating only four regions, we are in the lumper’s camp!

The USDA makes more distinction, with 10 zones based on average low winter temperatures. However, those of us who garden know that there are many times when we feel as if our garden is in a zone of its own.

The Western Region is not only the largest ACS region geographically, but also has the greatest range of climatic conditions, from the tropical Hawaii to the Rocky Mountain states of Colorado and Wyoming; from the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico to the rain forests of Western Washington. We clearly can’t all plant the same conifers and have them flourish, but we do look for similarities in conditions and try our best to understand the needs of each genus to try to make the best choices for our gardens.

Growing Regions and Droughts

While the West has a wide variety of climates, we do share a few common attributes. Most of the West, for example, enjoys much cooler summer nights than the states east of us. No matter how hot we get during the day, we can almost always count on the heat mitigating significantly once the sun goes down.

We also tend to have much drier summer air than the eastern two-thirds of the country. The cooler nights make it easier for many of us here to grow conifers which struggle in the South. The drier summer air means that those conifers native to places with warm weather humidity don’t do as well here as they do in Georgia. But all of the various climatic attributes which have occupied our collective Western consciousness when selecting plants have coalesced over the last couple of years into one: drought.

The conifer, Juniperus horizontalis ‘Blue Chip’

Adapting to Droughts and Other Conifer-Growing Conditions

And, it’s not just California; even the Pacific Northwest, the land of ‘liquid sunshine’ (as they cheerfully refer to rain), has seen lower-than-usual snowpack in Washington and severe drought ratings in Oregon. The Smithsonian Magazine reports that Arizona could be out of water in six years and scientists at UC Irvine and NASA recently completed a study which suggests that the groundwater reserves in the Colorado River Basin are being depleted at a rapid rate.

Most of us have long recognized the wisdom (although we often stubbornly refuse to heed it) of “right plant, right place.” Gardening success comes most easily when we choose plants suitable for the climate and setting. For much of the West, that means selecting plants which can withstand our lower water situation. While I will specifically discuss my own garden conditions, it is a simple matter to follow the same thought-process for your own climate, whether the prevailing adverse condition be drought, warm summer nights, or low winter temperatures.

Advantages of Conifer Cultivation in Harsh Conditions

Conifer lovers are fortunate, because compared to many other kinds of plants, in general, evergreen conifers are well prepared to deal with adverse conditions. These ancient plants evolved during a time of great climatic change in the world and consequently have dealt with conditions far more extreme than we are facing today.

They are wind-pollinated, hence are not affected by any asynchronicity between themselves and insects which might arise from drought or temperature fluctuations. They also can conserve nutrients by not being forced to produce a full, new set of leaves every year. They can photosynthesize if conditions are harsh and prevent—or delay—new growth.

Because they are always “in leaf ”, they can photosynthesize whenever conditions are right—they don’t have to wait for bud break. This also means that they can take advantage of irregular rainfall, even if it is outside of the normal growing season. It is interesting to note that conifers dominate in the mild climate of the Pacific Northwest—most other places dominated by conifers have much harsher climates (e.g. boreal forests). Why would that be?

The answer seems to be the modified Mediterranean climate of the PNW, which while it has mild, wet winters, also has mild but dry summers. The evergreens can produce food during the mild winters, when deciduous trees are bare and ineffective, and the summer dryness is hard on deciduous species, which can’t compensate by photosynthesizing in the other three seasons.

The drought-resistant Ginkgo biloba, in fall color

Dry Summers in The Coastal West

In fact, much of the coastal West enjoys a Mediterranean, or modified Mediterranean, climate. That means wet winters and dry summers, with much of our weather directly influenced by the Pacific Ocean. The conifers we plant in our gardens generally receive supplemental irrigation, but we cannot replicate humid summers with reliable rainfall.

With water a scarce commodity, most of us use drip irrigation, which does not humidify the air at all. The readings on the hygrometer at my house are in the 30-40% range from June-September. So, where do we go to find conifers which will not just survive, but flourish in this kind of summer-dry environment, especially when drought is always on our minds?

Going Native with Conifers

The first place to look, when seeking conifers which will do well in our gardens, is in our own native plant population. These conifers, such as Pinus contorta, Pinus ponderosa, Sequoia sempervirens, Pseudotsuga menziesii and Cupressus macrocarpa, have evolved to deal with the specific conditions of the area, so should work best in our gardens, right?

In California alone there are over 50 native conifers, about half of which have more garden-appropriate cultivars. Some of the darlings of the conifer aficionado’s collection are amongst these plants: Pinus contorta ‘Chief Joseph’ and ‘Taylor’s Sunburst’ and Picea engelmannii ‘Bush’s Lace’ and ‘Blue Harbor’. Where it gets tricky is that California is a big state, with coastal, mountainous and desert regions.

Sequoia sempervirens, for example, are only truly happy in a narrow band practically within sight of the Pacific, and Picea engelmannii prefer the moist slopes of the Klamath Ranges. I grow cultivars of all of these species here in my garden, but I wouldn’t classify them as “low water” conifers.

The Right Conifer for the Right Conditions

Going native sounds good, but doesn’t always produce the best choices. In addition, of garden-worthy note is Pinus ponderosa, which has several cultivars. Ponderosa pine has a long tap root, which makes it able to reach water sources. It needles, like those of Sequoia, absorb the gentle moisture from fog.

When seeking natives, focus on those which can handle the specific extreme, to which you will be subjecting them. Cupressus macrocarpa, for example, withstand low rainfall, poor soils and Pacific gales, so is an appropriate California native conifer for low-water situations.

The ‘Lone Cypress’ of the Pebble Beach golf course is a Cupressus macrocarpa and is said to be one of the most photographed trees in North America. It is estimated to be 250 years old and has survived not just wind and low rainfall but fire. Now there is a tough plant! The garden cultivars are lovely, with ‘Coneybearii Aurea’ and ‘Greenstead Magnificent’ among my very favorite of all of my conifers.

The conifer, Cupressus macrocarpa ‘Coneybearii Aurea’

Taking Conifers to Extreme Measures

Even better than many of our natives, the conifers which truly seem to deal with the dry summers and extended periods between waterings are those which are native to regions with extreme conditions. The Mediterranean conifers, for example, are the best equipped to handle less-frequent waterings.

Abies pinsapo (with some great cultivars such as ‘Horstmann’, ‘Glauca’ and ‘Aurea’) and cultivars of some of the cedars, such as Cedrus libani and Cedrus atlantica, are standout performers in my garden, and once established, can handle much less-frequent waterings than Sequoia sempervirens. There is a wide range of size, color and form amongst the cedar cultivars; thus, you can have quite a bit of variety within this one genus.

Conifers from other regions, such as those with mountainous terrain with irregular rainfall, appear to be able to soldier through less-than ideal conditions and still look attractive. Picea pungens, which are native to the Rocky Mountains, are prized for their intense blue color. That color results from wax on the needles which is believed to reduce their temperature, as well as transpiration and light absorption. That protective wax helps Colorado blue spruces retain moisture and deal with low-water conditions. Once established, Picea pungens cultivars are some of the summer-hardiest conifers in my garden.

Pinus mugo: A Tough Mountain Conifer

Pinus mugo hail from mountainous regions of Europe and Asia, many of which suffer severe, desiccating winds. Consequently, mugos have developed tough needles to retard water loss, enabling them to handle our dry summers. They have an exceptionally large native range, which yields the longest list of synonyms of any pine and a dizzying array of variation among the cultivars.

Some, such as ‘Mops’, ‘Sherwood Compact’, ‘Slowmound’ and ‘White Bud’ are reliably slow growing, so that, if you select one of these, you will avoid the dreaded guessing game of wondering how fast (and how large) your mugo will grow.

Conifer Focus: Junipers

Junipers as a genus are generally regarded as drought-tolerant and their wide distribution in the wild covers many arid areas. We have native Juniperus in rocky, dry areas in California, and there are others endemic to the Mediterranean, North Africa and other desert or quasi-desert locations. There are hundreds of juniper cultivars and almost all of the ones available in the trade can handle low-water conditions.

(Junipers have the added advantage of often being more reasonably priced than other genera; they do not command the respect of Abies koreana or Pinus parviflora! When I fell in love with a large Juniperus cedrus at a wholesale nursery and was astounded to hear how inexpensive it was, the owner explained: “It’s a juniper—no one will pay up for it.”) Likewise, Ginkgo biloba (while not a conifer, is a gymnosperm and under the ACS umbrella) is drought-tolerant and withstands poor conditions.

Keep it in the Family

Finally, once certain species have survived and flourished through several cycles of arid summers in the garden, the best chance of finding successful additions is to look for more species in that genus. It is not a coincidence that the list of conifers, which I have found most equipped to deal with drought conditions, are all members of the cypress and pine families (other than Ginkgo, which is, as usual, an exception!)

Within Pinaceae, certain genera are much more widely represented, with Pinus itself the most frequently occurring genus. While there are a few firs and spruce which do extremely well in drought conditions, there are far more which would languish, if not die outright. The cypress family representatives are all in the subfamily Cupressoideae.

It’s interesting that the members of this subfamily are native to the Western United States, with the exception of Microbiota decussata, or Siberian cypress, which, as its common name implies, is native to the mountainous region of southeastern Siberia. Even though it calls home a spot far from the rest of its subfamily, its morphology puts it amongst them and it shares with them the ability to endure drought.

The conifer, Juniperus squamata ‘Blue Star’

Actual Garden Drought Conditions

When I speak of drought-tolerant plants or gardening in a low-water environment, I do not mean to suggest that I provide no supplemen-tal water. Northern California generally only has rainfall between November and April. We had no rain at all between late December 2012 and December 2013.

An added complication is that many drought-tolerant plants are from places with poor, rocky soil. My local soil is clay-based and heavy (a mile away is General Vallejo’s Petaluma Adobe, the largest adobe building remaining in the United States, built in the mid-nineteenth century from adobe bricks made at the site). The clay is water-retentive and poorly draining.

Therefore, I add generous amounts of lava pebbles to increase drainage. Amending soil to accommodate plants which are native to other parts of the country or the world is a subject for a separate discussion; suffice it to say that it is as important as far less water than overhead spray and also reduces weeds.

Different Conifer Watering Needs